Trellis

Discussion

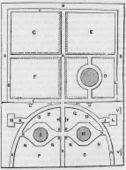

Trellis is a term used to describe a network of vertical, horizontal, and diagonal posts and rails designed to support vegetation. The term “treillage” was also used to refer to trellis work, especially in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century treatises; in the early nineteenth century the term “treliage” was noted on Charles Varlé’s plan of Bath (Berkeley Springs), Va. (later W.Va.). Trellis was also closely associated with espalier, especially by the mid-nineteenth century when the latter term referred to the support material (including trellis or lattice work) upon which fruit trees and ornamental trees were trained (see Espalier). Trellises also fulfilled a decorative function in the garden. In Batty Langley’s New Principles of Gardening (1728), the trellis was recommended as a framing device to direct a view to a distant focal point [Fig. 1]. Trellises could take on elaborate forms and were used for garden structures such as arbors and summerhouses (see Arbor and Summerhouse).[1] A.-J. Dézallier d’Argenville’s The Theory and Practice of Gardening (1712) indicates that such structures decreased in popularity in the early eighteenth century because they were relatively expensive for impermanent wooden structures. While Dézallier d’Argenville recommended treillage for decorative structures found in the pleasure ground, Thomas Jefferson (1804) insisted that “treillages” belonged in the kitchen garden, which suggests that he used them primarily for training fruit trees.

Seventeenth-, eighteenth-, and early nineteenth-century gardening treatises all generally describe the feature as supports for fruits trained against walls; therefore, trellises were located frequently in the walled kitchen garden. Placing fruit trees or fruit-bearing vegetation on trellises attached to walls was beneficial; the wall sheltered the fruit and radiated warmth that hastened its ripening. Moreover, affixing and spreading a tree or vine against a trellis often stimulated fruit production. For similar reasons, the trellis was used in hothouses and greenhouses, especially in the nineteenth century when specialized forcing houses became increasingly popular. In 1826, J.C. Loudon set forth seven types of trellises for hothouses and greenhouses, each differentiated by its location within these structures.

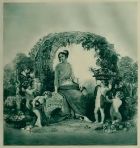

By the mid-nineteenth century, treatise writers such as A.J. Downing (1851) promoted the trellis for both cultivation of plant material and use as an ornamental feature. Trellises supporting decorative and sweet-smelling plant material, such as roses and honeysuckles, could be attached to the structure of the summerhouse, arbor, seat, outbuildings, and the house itself, often along the veranda [Fig. 2]. Trellises not only embellished the structure, but also, as Downing noted, offered “an air of rural refinement and poetry.” When used as freestanding elements in landscape designs, trellises functioned as semi-transparent walls. Like those at the Vassall-Craigie-Longfellow House in Cambridge, Mass. [Fig. 3], they were placed along borders and walkways and positioned to mask unsightly structures or elements, as Edward Sayers recommended in his 1838 treatise.

Trellis construction varied widely from simple post-and-rail grid patterns to intricate systems composed of horizontal, vertical, and diagonal elements of different lengths and widths. Many treatises contain detailed instructions for the construction of trellises, whose requirements depended upon the type of vegetation to be supported. George William Johnson’s Dictionary of Modern Gardening (1847), for example, explains different trellises according to the type of plant, vine, or tree to be supported, as well as describing their placement in greenhouses, hothouses, or along walks.

Until the nineteenth century, wood was commonly used for the feature, although in 1789 Thomas Sheridan also mentioned the use of iron. Some treatise writers recommended specific wood types. Philip Miller (1754), for example, reported that fir was commonly used, Bernard M’Mahon (1806) mentioned pine, and Downing (1851) suggested cedar. Treatise authors also debated whether wood trellises should be painted. By mid-century, the availability of relatively inexpensive metalwork (which could be worked into a variety of forms), allowed wider use of materials such as cast iron and wire.

-- Anne L. Helmreich

Images

Inscribed

Batty Langley, "Frontispieces of Trellis Work for the Entrances into Temples of View, Arbors, Shady Walks, &c.," in New Principles of Gardening (1728), pl.XVIII.

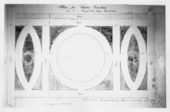

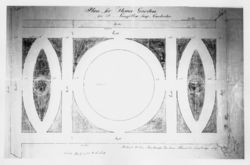

Batty Langley, "Shady walks with Temples of Trellis work after the grand manner of Versailles," and "An Avenue in Perspective, terminated with the ruins of an ancient Building after the Roman manner," in New Principles of Gardening (1728), pl.XXII.

J.C. Loudon, Statue of Mercury in front of trelliswork for creepers, in The Suburban Gardener (1838), p.585, fig.238.

J.C. Loudon, A walk covered with trelliswork, in The Suburban Gardener (1838), p.664, fig.280.

Alexander Walsh, "Plan of a Garden," in New England Farmer 19, no. 39 (Mar. 31, 1841): 308.

John J. Thomas, "Plan of a Garden," in The Cultivator 9, no. 1 (Jan. 1842): p.22, fig.8.

Richard Dolben, "Plan for Flower Garden," 1847.

Anonymous, Flowerpot Trellis in the Shape of an Urn or Vase, in George William Johnson, A Dictionary of Modern Gardening (1847), p.601, fig.168.

Anonymous, Flowerpot with Trellis, in George William Johnson, A Dictionary of Modern Gardening (1847), p.601, fig.169.

Anonymous, The Manner in Which the Wire-trellis for Climbing Plants is Attached to Pots, in George William Johnson, A Dictionary of Modern Gardening (1847), p.602, fig.170.

George William Johnson, Umbrella Trellis, in A Dictionary of Modern Gardening (1847), p.602, fig.171.

Associated

J.C. Loudon, Peach-Houses and Vineries, in An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1826), p.509, fig.450a-c.

Anonymous, "Small Bracketed Cottage," in A.J. Downing, The Architecture of Country Houses (1850), pl. opp. p.78, fig.9.

Anonymous, "Suburban Cottage," in A.J. Downing, The Architecture of Country Houses (1850), pl. opp. p.109, figs.33 and 34.

Anonymous, "Regular Bracketed Cottage," in A.J. Downing, The Architecture of Country Houses (1850), pl. opp. p.112, figs.37 and 38.

Anonymous, "Design for a Cottage for a Country Clergyman" and "Plan of Principal Floor," in A.J. Downing, ed., Horticulturist 6, no. 7 (July 1851): pl. opp. p.207.

Attributed

William Russell Birch, "New Lutheran Church, in Fourth Street Philadelphia," 1799.

William Russell Birch, "York-Island with a View of the Seats of Mr. A. Gracie, Mr. Church &c.," 1808, in William Russell Birch and Emily Cooperman, The Country Seats of the United States (2009), p.75, pl.17.

Alexander Jackson Davis, "The Conservatory," c.1839.

Alexander Jackson Davis, "View N.W. at Blithewood," c.1841.

Texts

Common Usage

- Jefferson, Thomas, 1804, describing Monticello, plantation of Thomas Jefferson, Charlottesville, Va. (quoted in Nichols and Griswold 1978: 111)[2]

- “The kitchen garden is not the place for ornaments of this kind. bowers and treillages suit that better, & these temples will be better disposed in the pleasure grounds.”

- Varlé, Charles, 1809, describing the improvement of the square and the town of Bath (Berkeley Springs), Va. (later W.Va.) (Library of Congress, Map Division)

- “E. Reservoir or Fountain covered with a vine treliage in a form of a dome or copula [sic].”

- Dearborn, H.A.S., 1832, describing Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, Mass. (quoted in Harris 1832: 83)[3]

- “the latter [monuments], at least, should be exposed from its base to its summit, and to accomplish this the space must remain open, or only be enclosed by the lightest constructed trellis, formed with iron posts and delicate pales, or small stone or iron posts and chains.”

- Teschemacher, James E., 1 November 1835, “On Horticultural Architecture,” describing the vicinity of Boston, Mass. (Horticultural Register 1: 411–12)

- “The vicinity of Boston abounds so much in every variety of beautiful landscape, that there is scarcely any place where art is less required in laying out pleasure grounds . . . the trellis covered with climbing roses leading to a rosarium . . . all this, owing to the natural advantages of the country surrounding Boston, may be accomplished at a comparatively trifling expense and loss of time.”

- Loudon, J.C., 1838, describing the Lawrencian Villa, residence of Mrs. Lawrence, Dayton Green, near London, England (p.584)[4]

- “and looking northwards, we have the statue of Mercury in the foreground, and behind it the camellia-house, the wall on each side of which is heightened with trelliswork for creepers.” [Fig. 4]

- Loudon, J.C., 1838, describing Kenwood, seat of the Earl of Mansfield, Hampstead, England (p.662–663)[4] back up to text

- “The impression is not lessened when we come within sight of the house . . . or when, passing through a walk covered with trelliswork, in the flower-garden, to the lawn front, we look down the declivity to the water, at the foot of the rising woods on the opposite bank.” [Fig. 5]

- Longfellow, Henry Wadsworth, c.1847, describing the Vassall-Craigie-Longfellow House, Cambridge, Mass. (quoted in Evans 1993: 43)[5]

- “The green trellis-work by the flower-garden was a part of an old covered walk to the outhouses. The gateway is from the old College house which stood opposite the bookseller’s in the college yard. In taking up this covered walk was found the skull of a dog, with a brass collar marked ‘Andrew Craigie.”

- Hovey, C.M., February 1850, “Notes on Gardens and Gardening in the neighborhood of Boston,” describing Bellmont Place, residence of John Perkins Cushing, Watertown, Mass. (Magazine of Horticulture 16: 50–51)

- “The inclosed space [between the greenhouse and the peach houses], of about two acres, forms the kitchen garden, which is finely laid out, trellised and planted with the finer sorts of pears, peaches, &c. These latter were on trellises, and protected with spruce branches, from the frost, or rather from the hot sun that succeeds it. I think this an excellent method; it is extensively practised with much benefit in the northern parts of Great Britain. In fact, without such partial protection, the culture of peaches would be all but impossible. The principles upon which the various operations of gardening are conducted about this place by Mr. Schimming, are thoroughly scientific, and manifest a perfect understanding of the numerous details connected with the higher branches of horticulture.”

- Ranlett, William H., 1851, describing Waldwic Cottage (formerly Little Hermitage), property of Elijah Rosencrantz, Hohokus, N.J. ([1851] 1976: 43)[6]

- “Ground plot for Waldwick Cottage. . . . These grounds are to be laid out and executed, and the out-buildings all placed according to this plot. . . . N N, grape arbor and trellis.”

Citations

- La Quintinie, Jean de, 1693, The Compleat Gard’ner ([1693] 1982: n.p.)[7]

- “A trail is a Trelliss, or Lattice frame made for the support of Wall and palisaded Trees. . . .

- “To trelliss, is to pallisade, nail up and fasten Trees upon Walls, or Pole-Hedges and on wooden Trails or Trellisses. . . .

- “Lattices, are the square works in wooden frames or Trellisses that support of Wall or palisaded Trees.”

- Miller, Philip, 1754, The Gardeners Dictionary ([1754] 1969: 1509–10)[8]

- “Where Persons are very curious to have good Fruit, they erect a Trelase against their Walls, which projects about two Inches from them, to which they fasten their Trees; which is an excellent Method, because the Fruit will be always at a proper Distance from the Walls, so as not to be injured by them, and will have all the Advantage of their Heat. . . .

- “These Trelases may be contrived according to the Sorts of Fruit which are planted against them. Those which are design’d for Peaches, Nectarines, and Apricots (which, for the most part, produce their Fruit on the young Wood), should have their Rails three, or, at most, but four, Inches asunder every Way: but for other Sorts of Fruit, which continue bearing on the old Wood, they may be five or six Inches apart; and those for Vines may be eight or nine Inches Distance. . . .

- “These Trelases may be made of any Sort of Timber, according to the Expence which the Owner is willing to bestow; but Fir is most commonly used for this Purpose, which, if well dried and painted, will last many Years; but if a Person will go to the Expence of Oak, it will last sound much longer. And if any one is unwilling to be at the Expence of either, then a Trelase may be made of Ash-poles, in the same manner as is practiced in making Espaliers; with this Difference only, that every fourth upright Rail or Post should be very strong, and fasten’d with iron Hooks to the Wall, which will support the Whole: and as these Rails must be laid much closer together, than is generally practiced for Espaliers, these strong upright Rails or Posts will not be farther distant than three Feet from each other. To these the cross Rails which are laid horizontally should be well nail’d, which will secure them from being displaced, and also strengthen the Trelase; but to the other smaller upright Poles, they need only be fasten’d with Wire. To these Trelases the Shoots of the Trees should be fasten’d with Ozier-twigs, Rope-yarn, or any other sort Bandage; for they must not be nail’d to it, because that will decay the Wood-work.

- “These Trelases need not be erected until the Trees are well spread, and begin to bear Fruit plentifully; before which time the young Trees may be trained up against any ordinary low Espaliers, made only of a few slender Ash-poles, or any other slender Sticks; by which Contrivance the Trelases will be new when the Trees come to Bearing, and will last many Years after the Trees have overspread them; whereas, when they are made before the Trees are planted, they will be decayed before the Trees attain half their Growth.”

- Sheridan, Thomas, 1789, A Complete Dictionary of the English Language (n.p.)[9]

- “TRELLIS, trel’-lis. s. Is a structure of iron, wood, or osier, the parts crossing each other like a lattice.”

- Gardiner, John, and David Hepburn, 1804, The American Gardener (p.113)[10]

- “Trellisses for tying the vines to, must be completed this month [March]; they should be five feet high, the stakes about three feet asunder, and have four cross rails.”

- M’Mahon, Bernard, 1806, The American Gardener’s Calendar (pp.16–17)[11]

- “Espaliers are hedges of fruit-trees, which are trained up regularly to a lattice or trellis of wood work, and are commonly arranged in a single row in the borders, round the boundaries of the principal divisions of the kitchen-garden. . . .

- “For common espalier fruit-trees in the open ground, a trellis is absolutely necessary, and may either be formed of common stakes or poles, or of regular joinery work, according to taste or fancy.

- “The cheapest, the easiest, and soonest made trellis for common espalier trees, is, that formed with straight poles, being cut into proper lengths, and driving them into the ground, in a range, a foot distance, all of an equal height, and then railed along the top with the same kind of poles or slips of pine or other boards, nailed down to each stake, to preserve the whole straight and firm in a regular position; to which the branches of the espalier trees are to be fastened with small osier-twigs, rope yarn, &c. and trained along horizontally from stake to stake, as directed for the different sorts under their proper heads.

- “To render the above trellis still stronger, run two or three horizontal ranges of rods or small poles along the back parts of the uprights, a foot or eighteen inches asunder, fastening them to the upright stakes, either with pieces of strong wire twisted two or three times round, or by nailing them.

- “But when more elegant and ornamental trellis’s of joinery work are required in any of the departments, they are formed with regularly squared posts and rails, of good durable timber, neatly planed and framed together, fixing the main posts in the ground, ten or twelve feet asunder, with smaller ones between, ranging the horizontal railing from post to post, in three or more ranges; the first being placed about a foot from the bottom, a second at top, and one or two along the middle space, and if thought convenient, may range one between each of the intermediate spaces; then fix thin slips of lath, or the like, upright to the horizontal railing, ten inches or a foot asunder; and paint the whole with oil colour, to render it more ornamental and durable; and in training the trees, tie their branches both to the railing of the trellis, and to the upright laths, according as they extend in length on each side.”

- Abercrombie, John, with James Mean, 1817, Abercrombie’s Practical Gardener (p.180) [12]

- “Espaliers have the branches trained to an upright superficial trellis, standing detached from a wall, and thus bear on both sides.”

- Loudon, J.C., 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (pp.308, 328)[13]

- “1575. Trellised walls are sometimes formed when the material of the wall is soft, as in mud walls; rough, as in rubble-stone walls, or when it is desired not to injure the face of neatly finished brick-work. Wooden trellises have been adopted in several places, especially when the walls are flued. . . .

- “1671. Trellises are of the greatest use in forcing-houses and houses for fruiting the trees of hot climates. On these the branches are readily spread out to the sun, of whose influence every branch, and every twig and single leaf partake alike, whereas, were they left to grow as standards, unless the house were glass on all sides, only the extremities of the shoots would enjoy sufficient light. The advantages in point of air, water, pruning, and other parts of culture, are equally in favor of trellises, independently altogether of the tendency which proper training has on woody fruit-trees, to induce fruitfulness.

- “1672. The material of the trellis is either wood or metal; its situation in culinary hot-houses is against the back wall, close under the glass roof, or in the middle part of the house, or in all these modes. . . .

- “1673. The back wall trellis. . . .

- “1674. The middle trellis. . . .

- “1675. The front or roof trellis. . . .

- “1676. The fixed rafter-trellis. . . .

- “1677. The moveable rafter-trellis. . . .

- “1678. The secondary trellis. . . .

- “1679. The cross trellis.”

- Webster, Noah, 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (n.p.)[14]

- “TREILLAGE, n. trel’lage. [Fr. from treillis, trellis.]

- “In gardening, a sort of rail-work, consisting of light posts and rails for supporting espaliers, and sometimes for wall trees. Cyc. . . .

- “TREL’LIS, n. [Fr. treillis, grated work.] In gardening, a structure or frame of cross-barred work, or lattice work, used like the treillage for supporting plants.”

- Fessenden, Thomas Green, 1828, The New American Gardener (p.294)[15]

- “VINE.—Vitis.—Many gentlemen in this neighbourhood have given considerable attention to the cultivation of grapes in the open air upon open trellises, and some have succeeded remarkably well.”

- Bridgeman, Thomas, 1832, The Young Gardener’s Assistant (pp.111, 134)[16]

- “In a retired part of the [flower] garden, a rustic seat may be formed, over and around which honey-suckles and other sweet and ornamental creepers and climbers may he [sic] trained on trellises, so as to afford a pleasant retirement. . . .

- “When Shrubs, Creepers, or Climbers are planted against walls or trellises, either on account of their rarity, delicacy, or to conceal a rough fence or other unsightly object, they require different modes of training.”

Notes

- ↑ Jellicoe, Sir Geoffrey et al., eds. 1986. The Oxford Companion to Gardens. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 53. view on Zotero

- ↑ Nichols, Frederick Doveton, and Ralph E. Griswold. 1978. Thomas Jefferson, Landscape Architect. Charlottesville, Va.: University Press of Virginia. view on Zotero

- ↑ Harris, Thaddeus William. 1832. A Discourse Delivered before the Massachusetts Horticultural Society on the Celebration of Its Fourth Anniversary, October 3, 1832. Cambridge, Mass.: E. W. Metcalf. view on Zotero

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Loudon, J.C. (John Claudius). 1838. The Suburban Gardener, and Villa Companion. London: Longman et al. view on Zotero

- ↑ Evans, Catherine. 1993. Cultural Landscape Report for Longfellow National Historic Site, History and Existing Conditions. Vol. 1. Boston: National Park Service, North Atlantic Region. view on Zotero

- ↑ Ranlett, William H. [1851]1976. The Architect. 2 vols. New York: Da Capo. view on Zotero

- ↑ La Quintinie, Jean de. [1693]1982. The Compleat Gard’ner, or Directions for Cultivating and Right Ordering of Fruit-gardens and Kitchen Gardens. Translated by John Evelyn. New York: Garland. iew on Zotero

- ↑ Miller, Philip. [1754] 1969. The Gardeners Dictionary. New York: Verlag Von J. Cramer. view on Zotero

- ↑ Sheridan, Thomas A. A Complete Dictionary of the English Language, Carefully Revised and Corrected by John Andrews.... 5th ed. Philadelphia: William Young, 1789. view on Zotero

- ↑ Gardiner, John, and David Hepburn. 1804. The American Gardener, Containing Ample Directions for Working a Kitchen Garden Every Month in the Year, and Copious Instructions for the Cultivation of Flower Gardens, Vineyards, Nurseries, Hop Yards, Green Houses and Hot Houses. Washington, D.C.: Printed by Samuel H. Smith. iew on Zotero

- ↑ M’Mahon, Bernard. 1806. The American Gardener’s Calendar: Adapted to the Climates and Seasons of the United States. Containing a Complete Account of All the Work Necessary to Be Done... for Every Month of the Year.... Philadelphia: Printed by B. Graves for the author. view on Zotero

- ↑ Abercrombie, John. 1817. Abercrombie’s Practical Gardener or, Improved System of Modern Horticulture. London: T. Cadell and W. Davies. [Abercrombie, John. 1817. Abercrombie’s Practical Gardener or, Improved System of Modern Horticulture. London: T. Cadell and W. Davies. view on Zotero]

- ↑ Loudon, J.C. (John Claudius). 1826. An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening. 4th ed. London: Longman et al. view on Zotero

- ↑ Webster, Noah. 1828. An American Dictionary of the English Language. 2 vols. New York: S. Converse. view on Zotero

- ↑ Fessenden, Thomas, ed. 1828. The New American Gardener. 1st ed. Boston: J.B. Russell. view on Zotero

- ↑ Bridgeman, Thomas. 1832. The Young Gardener’s Assistant. 3rd ed. New York: Geo. Robertson. view on Zotero