Obelisk

The term obelisk was used in the American colonies and early Republic to refer to a slender shaft or pillar with four faces that diminished in width from the base to a pyramidal top. Obelisks were generally made of wood, granite, marble, or, as Jefferson prescribed for his tombstone, "coarse stone."

Definition

The term obelisk was used in the American colonies and early Republic to refer to a slender shaft or pillar with four faces that diminished in width from the base to a pyramidal top. Obelisks were generally made of wood, granite, marble, or, as Jefferson prescribed for his tombstone, "coarse stone." According to Batty Langley in New Principles of Gardening (1728), they could also be made of trellis work and covered with climbing plants to give the effect of a living obelisk. Some obelisks were placed upon pedestals that were cube or temple forms; others rose directly from the ground.

In the designed landscape, the obelisk served two functions: as a garden ornament and as a monument with emblematic significance. Obelisks were important in the designed landscape or pleasure garden because they punctuated the vista or provided a place from which to gain a view. In order to serve these purposes, treatise authors recom- mended placing obelisks on elevated sites, although this treatment was not always used. Obelisks, which varied in size, were placed either in the center of open spaces or at the terminus of circulation routes. In both cases, they served as focal points. They often appeared in openings where radial sight lines were clear, as indicated by Hannah Callender in her 1762 description of Judge William Peters's estate, Belmont Mansion, near Philadelphia, where she wrote that the avenue "looks to the obelisk."

In nineteenth-century America, the obelisk was utilized on a monumental scale in public landscape design. Some examples were built as hollow shafts that could be ascended by means of an internal staircase leading to interior lookout platforms or external galleries, allowing the visitor a panoramic view of the surrounding landscape.[1] Solomon Willard's Bunker Hill Monument in Boston was the earliest obelisk of this type, dating from 1825 [Fig. 1].[2] Monumental obelisks were also striking landmarks in the relatively low urban skylines of the first half of the nineteenth century. Robert Mills, architect of the Washington Monument in Washington, D.C., designed several monumental obelisks that served both as observation towers and civic displays.[3]

The obelisk's rich antique associations imbued it with symbolic significance. Its origins in Egypt, prominence in the Roman world, and, since the Renaissance, use in gardens and parks lent a vocabulary of the exotic and the historic to American landscape design. Several collected treatise cita- tions recount the best-known examples of ancient obelisks, many of which have survived into the modern period. Excavations in Rome during the seventeenth century, for example, revealed dozens of Egyptian obelisks that were reerected throughout the city. At the same time, modern obelisks ornamented French gardens such as Versailles. Many great gardens in Britain in the eighteenth century also featured obelisks: Castle Howard, Chiswick House, Holkham Hall, and Montacute House, to name a few.[4] With the French invasion of Egypt in 1798, the taste for Egyptian statuary and styles increased and obelisks appeared more frequently as props in gardens.[5] Thus the tradition of obelisks in European gardens and public spaces transmitted via literature, European designers, and American visitors abroad, was a significant influence onAmerican garden practice. Both Ephraim Chambers (1741–43) and Noah Webster (1828) described the use of hieroglyphic inscriptions on obelisks that expressed the historic tradition from which the form derived.

In America, the choice of the obelisk for political commemoration in public spaces was recorded in the revolutionary period at Williamsburg, Va., where the monument was intended to honor those who opposed the Stamp Act. The repeal of that act was celebrated by the erection of a temporary obelisk in the Boston Common, as illustrated in a print by Paul Revere [Fig. 2]. After the War of Independence, Pierre-Charles L'Enfant specified obelisks as decorations in the new capital city that would memorialize the heroes of the Revolution. His plan of 1792 indicated these monuments embellishing the public squares of the new capital. The association with republican Rome, the site of many obelisks, was a frequent iconographic reference in early federal decoration and rhetoric. The obelisk was a popular public and political monument, as Robert Mills argued, not only because of its association with antiquity and republicanism, but also because its surfaces allowed inscriptions that could particularize the memorial function. He described, for example, how the ornamentation on his design for the Bunker Hill obelisk symbolized the states' formation of the federal union.

The Egyptian obelisk was appropriate for the expression of early national symbolism because of the equation of the newly formed United States with another "first civilization." Freemasonry also fostered the link with ancient Egypt. The obelisk exemplified "cubic architecture" preferred by the Burlington circle of Freemason architects, derived from Palladio and James Gibbs and practiced in America by Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Henry Latrobe. It was seen as a repudiation of baroque eclecticism, as well as colonial red-brick Anglo-Dutch architec- ture. For American Freemasons, building took on a political cast that extended into the garden.[6]

Mills pointed out that its diminishing width made the obelisk lighter and more graceful than another popular monument form, the column. Solomon Willard preferred the obelisk to the column, the latter being too "splendid." It was both the picturesque effect as well as the historical significance of the obelisk that motivated J. C. Loudon's recommendation of it in the garden.

The wave of monument building and civic improvement that marked the early Federal period carried with it an increasing number of obelisks. Chevalier Charles François Adrien le Parlmier d'Annemours's estate, Belmont, in Baltimore, featured an obelisk built in honor of Christopher Columbus; and Ashley Hall in Charleston, S.C., displayed one in memory of Lt. Gov. William Bull [Fig. 3].

The visual and textual evidence surrounding Charles Willson Peale's obelisk represents a clear correlation between usage, treatise citation, and image based on early American primary sources. Peale noted his reliance on G. Gregory's definition in the Dicionary of Arts and Sciences (1806–7, 1816) in building an obelisk in his garden at Belfield. Gregory's description gave the proportions and dimensions of the "truncated, quadrangular, and slender pyramid" that Peale sketched in his letters and inscribed on an obelisk [Fig. 4]. The emblematic significance of this obelisk was also suggested in Gre- gory's treatise description of the obelisk built to memorialize Ptolemy Philadelphus, the ancient Egyptian who built the great obelisk lighthouse and library at Alexandria, and after whom Peale of Philadelphia may have been modeling himself.

Jefferson and Peale's garden obelisks served private but also commemorative purposes as both men planned to use the forms garden features that would eventually become their tombstones. In each case, these public figures mixed political and private associations in their choice of inscriptions. In addition to the political significance, the use of the Egyptian obelisk for funereal ornamentation was well established in America. The discussion surrounding the designs for Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Mass., conveyed the popular interest in Egyptian-style monuments and architec- ture in early rural cemeteries. Defenders of the plans for the cemetery called it an "architecture of the dead" because nearly all surviving Egyptian architecture or monuments had a funerary purpose.[7] The Egyptian practice of placing the tomb "in the midst of the beauty and luxuriance of nature"[8] was also cited as justification for this new garden type. [Figs. 5 and 6]. The obelisk had a long and continuous tradition in American landscape design that began in the colonies and lasted well into the nineteenth century. The feature was utilized in both public and private gardens ranging in scale from a few feet to the tallest edifices in American architecture until the advent of the skyscraper. Obelisks persisted over time despite changes in garden styles, finding a place within the Anglo-Dutch landscapes of Williamsburg, Va., in the mid-eighteenth century, as well as in the picturesque landscapes of rural cemeteries one hundred years later.

--Therese O'Malley

Images

Inscribed

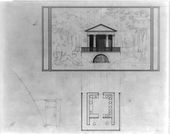

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Houses and a church. Garden plan with outbuildings, 1795-1799.

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Houses and a church. Spring house - elevation and plan, 1795-1799.

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, "Taste. Anno 1620," in "Essay on Landscape" (1798-1799).

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Studies of Trees, in "Essay on Landscape" (1798-1799).

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Studies of Trees, in "Essay on Landscape" (1798-1799).

Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Plan of the Capitol grounds, 1815.

Notes

- ↑ John Zukowsky, "Monumental American Obelisks: Centennial Vistas," Art Bulletin 58 (December 1976): 574–81. view on Zotero

- ↑ Zukowsky argues that the American monumental obelisk was a combination of the solid obelisk and the hollow memorial column. As it developed through the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the monumental obelisk was a formally unique and distinctly American monument type that had military connotations and served as an image of continental expansion and unity during the centennial era. See Zukowsky, "Monumental American Obelisks," 581.

- ↑ Mills designed four monumental obelisks during his career. Pamela Scott, "Robert Mills and American Monuments," in Robert Mills, Architect, ed. John M. Bryan (Washington, D.C.: American Institute of Architects Press, 1989), 143–77. view on Zotero

- ↑ Geoffrey Jellicoe et al., eds., Oxford Companion to Gardens (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1986), 408. view on Zotero

- ↑ For information on the Egyptian style in America, see Richard G. Carrott, The Egyptian Revival: Its Sources, Monuments, and Meaning, 1808–1858 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1978). view on Zotero

- ↑ Roger Kennedy, Orders from France (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1990), 431. view on Zotero

- ↑ Mount Auburn Cemetery was originally to be named the "American Père Lachaise." Although the name was not given, Mount Auburn Cemetery was often compared with Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris. Richard Etlin recounts the history of this French cemetery as an influential landscape continued in America. He discusses the Egyptian style of much of that cemetery's architecture and monuments. See Richard Etlin, The Architecture of Death: The Transformation of the Cemetery in Eighteenth-Century Paris (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1984), 358–68. view on Zotero

- ↑ Blanche Linden-Ward, Silent City on the Hill: Landscapes of Memory and Boston's Mount Auburn Cemetery (Columbus: Ohio State University, 1989), 261–66. view on Zotero