Difference between revisions of "Benjamin Vaughan"

V-Federici (talk | contribs) m |

V-Federici (talk | contribs) m (→History) |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

==History== | ==History== | ||

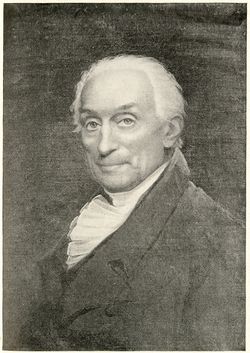

| + | [[File:2289.jpg|thumb|Fig. 1, Dr. Benjamin Vaughan, Hallowell, ca. 1800.]] | ||

Born in Jamaica where his father, the British merchant and planter [[Samuel Vaughan]] owned two large [[plantation]]s, Benjamin Vaughan was educated in Britain and pursued degrees in law and medicine at Cambridge and the University of Edinburgh. He gravitated toward a group of radical thinkers (among them Sir Joseph Banks, Joseph Priestly, and Jeremy Bentham) who shared his unorthodox views on religion, politics, and science.<ref>Andrew J. Hamilton, “Atlantic Cosmopolitanism and Nationalism: Benjamin Vaughan and the Limits of Free Trade in the Eighteenth Century” (PhD diss., University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2004), 91–127, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/R68AI8KM view on Zotero]; Craig Compton Murray, “Benjamin Vaughan (1751–1835): The Life of an Anglo-American Intellectual” (PhD diss., Columbia University, 1989), 209, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/KUPH6CQ8 view on Zotero].</ref> Vaughan was sympathetic to the cause of American independence and sought out prominent Americans in London, including [[Thomas Jefferson]], Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, and William Bingham. At the outset of the Revolutionary War, he began editing Franklin’s writings (published in 1779 as ''Political, Miscellaneous, and Philosophical Pieces''), and he was instrumental in convincing Franklin to publish an autobiography.<ref>Peter Stallybrass, “Benjamin Franklin: Printed Corrections and Erasable Writing,” ''Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society'' 150 (December 2006): 563–65, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/RD8VSH95 view on Zotero]; Benjamin Franklin, ''The Papers of Benjamin Franklin'', ed. Barbara B. Oberg, 47 vols. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995), 31:210–18, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/7JVNSB2H view on Zotero]; Ellen Cohn, “Benjamin Franklin, Benjamin Vaughan, and Political, Miscellaneous and Philosophical Pieces,” in ''Benjamin Franklin, An American Genius'', ed. Gianfranca Balestra and Luigi Sampietro (Rome: Bulzoni, 1993), 149–61, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/6KCWUSQN view on Zotero]; see also Benjamin Vaughan to Benjamin Franklin, January 31, 1783, Paris, “The Electric Ben Franklin,” [http://www.ushistory.org/franklin/autobiography/page35.html website].</ref> As private agent to the Earl of Shelburne (then British Prime Minister), Vaughan facilitated peace negotiations between Britain and America in 1782. He thereafter served as an important conduit for the flow of scientific information and materials between the two countries, sending books and scientific equipment to Ezra Stiles (then president of Yale University) and the American Philosophical Society (which elected him a member in 1786), and carrying out a lengthy correspondence focused on medical and scientific news with Benjamin Rush.<ref>Murray 1989, 206, 216, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/KUPH6CQ8 view on Zotero].</ref> | Born in Jamaica where his father, the British merchant and planter [[Samuel Vaughan]] owned two large [[plantation]]s, Benjamin Vaughan was educated in Britain and pursued degrees in law and medicine at Cambridge and the University of Edinburgh. He gravitated toward a group of radical thinkers (among them Sir Joseph Banks, Joseph Priestly, and Jeremy Bentham) who shared his unorthodox views on religion, politics, and science.<ref>Andrew J. Hamilton, “Atlantic Cosmopolitanism and Nationalism: Benjamin Vaughan and the Limits of Free Trade in the Eighteenth Century” (PhD diss., University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2004), 91–127, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/R68AI8KM view on Zotero]; Craig Compton Murray, “Benjamin Vaughan (1751–1835): The Life of an Anglo-American Intellectual” (PhD diss., Columbia University, 1989), 209, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/KUPH6CQ8 view on Zotero].</ref> Vaughan was sympathetic to the cause of American independence and sought out prominent Americans in London, including [[Thomas Jefferson]], Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, and William Bingham. At the outset of the Revolutionary War, he began editing Franklin’s writings (published in 1779 as ''Political, Miscellaneous, and Philosophical Pieces''), and he was instrumental in convincing Franklin to publish an autobiography.<ref>Peter Stallybrass, “Benjamin Franklin: Printed Corrections and Erasable Writing,” ''Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society'' 150 (December 2006): 563–65, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/RD8VSH95 view on Zotero]; Benjamin Franklin, ''The Papers of Benjamin Franklin'', ed. Barbara B. Oberg, 47 vols. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995), 31:210–18, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/7JVNSB2H view on Zotero]; Ellen Cohn, “Benjamin Franklin, Benjamin Vaughan, and Political, Miscellaneous and Philosophical Pieces,” in ''Benjamin Franklin, An American Genius'', ed. Gianfranca Balestra and Luigi Sampietro (Rome: Bulzoni, 1993), 149–61, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/6KCWUSQN view on Zotero]; see also Benjamin Vaughan to Benjamin Franklin, January 31, 1783, Paris, “The Electric Ben Franklin,” [http://www.ushistory.org/franklin/autobiography/page35.html website].</ref> As private agent to the Earl of Shelburne (then British Prime Minister), Vaughan facilitated peace negotiations between Britain and America in 1782. He thereafter served as an important conduit for the flow of scientific information and materials between the two countries, sending books and scientific equipment to Ezra Stiles (then president of Yale University) and the American Philosophical Society (which elected him a member in 1786), and carrying out a lengthy correspondence focused on medical and scientific news with Benjamin Rush.<ref>Murray 1989, 206, 216, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/KUPH6CQ8 view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

Revision as of 11:51, February 12, 2021

Benjamin Vaughan (April 19, 1751–December 8, 1835) was an agriculturalist, physician, politician, and merchant. He is chiefly known for fostering diplomatic relations and cooperation in matters of science between Britain and America, and for creating a noteworthy landscape at his estate in the town of Hallowell, Maine.

History

Born in Jamaica where his father, the British merchant and planter Samuel Vaughan owned two large plantations, Benjamin Vaughan was educated in Britain and pursued degrees in law and medicine at Cambridge and the University of Edinburgh. He gravitated toward a group of radical thinkers (among them Sir Joseph Banks, Joseph Priestly, and Jeremy Bentham) who shared his unorthodox views on religion, politics, and science.[1] Vaughan was sympathetic to the cause of American independence and sought out prominent Americans in London, including Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, and William Bingham. At the outset of the Revolutionary War, he began editing Franklin’s writings (published in 1779 as Political, Miscellaneous, and Philosophical Pieces), and he was instrumental in convincing Franklin to publish an autobiography.[2] As private agent to the Earl of Shelburne (then British Prime Minister), Vaughan facilitated peace negotiations between Britain and America in 1782. He thereafter served as an important conduit for the flow of scientific information and materials between the two countries, sending books and scientific equipment to Ezra Stiles (then president of Yale University) and the American Philosophical Society (which elected him a member in 1786), and carrying out a lengthy correspondence focused on medical and scientific news with Benjamin Rush.[3]

Vaughan had presumably been introduced to the subjects of botany and agricultural improvement by the naturalist John Reinhold Forster, who had been one of his teachers at the Warrington Academy in England. He conferred frequently on these topics with Sir Joseph Banks and with naturalists in the British West Indies.[4] He was actively engaged in the exchange of seeds between America, the West Indies, Britain, and France. During the 1780s and early 1790s, in addition to disseminating among his friends in England specimens from John Bartram's “list of American plants fit for this country,” he arranged for West Indian rice seeds to be sent to a number of his correspondents in Virginia—including Thomas Jefferson and George Washington—and South Carolina, including Henry Laurens and Charles C. Pinckney.[5]

Vaughan’s support of republicanism and his sympathy for the French Revolution placed him at odds with the British government. In 1794 he fled to France, taking refuge at the country estate of Thomas Jefferson's brother-in-law, the American counsel-general, Henry Skipwith of Hors du Monde, Virginia.[6] Three years later, Vaughan immigrated to America with the intention of leading the exemplary life of “a peasant” in rural Hallowell, Maine. In addition to laying out extensive gardens, he developed a large portion of the property as a model farm, building greenhouses and planting orchards in order to experiment with the cultivation of a wide range of plant specimens: apple, pear, and stone-fruit scions imported from England; fig and grape cuttings that his brother John sent from France; potatoes imported from continental Europe; Swedish turnips; and Siberian wheat.[7] He established a successful commercial nursery and employed an English mechanic to set up New England’s largest cider mill and press. Dr. Vaughan sought to overcome local resistance to his family’s practice of “book farming” by conducting information sessions at his farm and by generously sharing plant and seed specimens.[8]

As a conduit for the exchange of scientific information, Vaughan was as active in his remote Maine outpost as he had been in London, publishing articles on his agricultural experiences and penning letters to correspondents as far flung as David Hosack in New York, Benjamin Rush in Philadelphia, and David Ramsay in South Carolina.[9] In 1800 he published an “augmented” version of The Rural Socrates, or, An Account of a Celebrated Philosophical Farmer Lately Living in Switzerland and Known by the Name of Kliyogg, which concerned a Swiss peasant who transformed a failing farm into a productive enterprise through attention to proper methods.[10] Over the course of his long friendship with Bowdoin College professor Parker Cleaveland (cousin of Nehemiah Cleaveland), Vaughan contributed scientific apparatus and collections to help promote study of the natural sciences at Bowdoin.[11] In 1805 he began campaigning to raise money for the establishment of a natural history professorship and experimental botanic garden at Harvard. By the time of his death, Vaughan had assembled one of the largest private libraries in New England, estimated at between 10,000 and 12,000 volumes, primarily imported from England and France.[12] According to the Hallowell journalist Samuel Lane Boardman (1836–1914), Vaughan’s library contained “many rare and valuable English works on agriculture and rural economy not often met with in public libraries of this country.”[13] A number of these volumes, heavily marked with his annotations, formed part of the large donations Vaughan made to New England institutions, including Harvard University and Bowdoin College.[14]

—Robyn Asleson

Texts

- Dwight, Timothy, 1807, describing Benjamin Vaughan’s estate in Hallowell, ME (1821: 2:218–19)[15]

- “A more romantic spot is not often found, than that on which stands the house of Mr. [Benjamin] V[aughan]. a descendant of Mr. Hallowell, from whom this town took its name; inheriting from him, it is said, a large landed estate in this country. He is a native of England; and has been heretofore a member of the British Parliament. His house stands on one of the elevated levels, mentioned above, where the hill, bends from its general Southern direction toward the West, and, forming an obtuse, circular point, furnishes a beautiful Southern, as well as Northern and Eastern, prospect. . . .

- “With this interesting family we spent the evening and the succeeding morning until 11 o’clock; and enjoyed in a high degree the combined pleasures of intelligence, politeness, and refinement. Mr. V. had proposed to carry us to a fine view of the country, furnished by a neighbouring eminence: but a mist, rising from the river during the night, precluded us from this gratification, until it became so late, that we were obliged to pursue our journey.”

- Bradford, Alden, 1842, describing Benjamin Vaughan’s estate in Hallowell, ME (1842: 409)[16]

- “Mr. Vaughan intended his residence here from the first to be permanent; and at once cultivated his grounds, and attended to the duties of a citizen, but without engaging in party disputes, as many do when they arrive in the United States. He wisely kept aloof from all political parties. He encouraged a taste for agriculture, and prepared a large nursery of fruit trees, which he distributed gratis in different parts of that new country, where they were much wanted. For twenty years past, the fruit in and near Hallowell, and in the neighboring towns, has been abundant — owing in a great measure to the generous efforts of Mr. Vaughan. He and his family distributed a great number of books for children in that part of the country; and urged the forming of schools in all the new plantations. The benefits have been extensive, and hardly can be duly appreciated.”

- Gardiner, Robert Hallowell, 1859, describing Benjamin Vaughan’s agricultural interests (1859: 6:90–91)[17]

- “Here [at Hallowell, Maine] he occupied himself in study in an extensive correspondence with distinguished persons on both sides the Atlantic and in promoting the welfare of the place and of the people among whom he had fixed his residence. . . The agriculture of the country was indebted to Dr Vaughan for the introduction of new varieties of seed and plants and for the importation of improved breeds of animals. His fortune was considerably diminished by the large sums expended upon his farm and nursery. . .”

- Sheppard, John H. 1865, describing Benjamin Vaughan’s agricultural interests (1865: 14)[18]

- “Dr. Vaughan was fond of horticulture, and was one of the pioneers of New England in the improvement of fruits and cereals. He imported choice seeds, which he was ever ready to impart to his neighbors. . . He also took great pains in promoting agriculture, and introducing from abroad the best kinds of stock on his farm; superior oxen and more productive cows were not to be seen.”

- Boardman, Samuel Lane, 1865, describing Benjamin Vaughan’s daily habits (1865: 188)[19]

- “A gentleman who was acquainted with Dr. Vaughan, and from whom I have obtained some incidents of his life, says it was his custom in fair weather to walk a certain number of miles, each day, for exercise; and when the weather would not admit of his being out of doors, he would walk upon his piazza as many hours as would be equivalent to the distance walked.”

Other Resources

Library of Congress Name Authority File

American National Biography Online

Benjamin Vaughan Papers, American Philosophical Society

Charles Vaughan Papers, Bowdoin College

Benjamin and William Oliver Vaughan Papers, 1774-1830

Vaughan Family Papers, 1768-1950, Massachusetts Historical Society

Notes

- ↑ Andrew J. Hamilton, “Atlantic Cosmopolitanism and Nationalism: Benjamin Vaughan and the Limits of Free Trade in the Eighteenth Century” (PhD diss., University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2004), 91–127, view on Zotero; Craig Compton Murray, “Benjamin Vaughan (1751–1835): The Life of an Anglo-American Intellectual” (PhD diss., Columbia University, 1989), 209, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Peter Stallybrass, “Benjamin Franklin: Printed Corrections and Erasable Writing,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 150 (December 2006): 563–65, view on Zotero; Benjamin Franklin, The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, ed. Barbara B. Oberg, 47 vols. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995), 31:210–18, view on Zotero; Ellen Cohn, “Benjamin Franklin, Benjamin Vaughan, and Political, Miscellaneous and Philosophical Pieces,” in Benjamin Franklin, An American Genius, ed. Gianfranca Balestra and Luigi Sampietro (Rome: Bulzoni, 1993), 149–61, view on Zotero; see also Benjamin Vaughan to Benjamin Franklin, January 31, 1783, Paris, “The Electric Ben Franklin,” website.

- ↑ Murray 1989, 206, 216, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Murray 1989, 210, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson, The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, ed. Julian P. Boyd, 41+ vols. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1961) 16: 274–76, view on Zotero; Charlotte M. Porter, “Philadelphia Story: Florida Gives William Bartram a Second Chance,” Florida Historical Quarterly 71 (January 1993): 319–20, view on Zotero; Murray 1989, 206–8, 216, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Robert Hallowell Gardiner, “Memoir of Benjamin Vaughan, M.D. and LL.D.,” Collections of the Maine Historical Society 6 (1859): 89, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Murray 1989, 384–85, 511, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Henry D. Kingsbury and Simeon L. Deyo, eds., Illustrated History of Kennebec County, Maine; 1625–1799–1892, 2 vols. (New York: H. W. Blake & Company, 1892), 1:191, view on Zotero; Samuel L. Boardman, “Appendix to Report on Kennebec County,” in Twelfth Annual Report of the Secretary of the Maine Board of Agriculture (Augusta, ME: Stevens & Sayward, Printers to the State, 1867), 220 view on Zotero.

- ↑ Murray 1989, 385, 519, view on Zotero; Kingsbury and Deyo, 1892, 1:191, 220, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Murray 1989, 386, view on Zotero.

- ↑ John C. Green and John G. Burke, “The Science of Minerals in the Age of Jefferson,” Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 68 (1978): 78–79, 83, 89, 102, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Murray 1989, 500, 503, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Samuel L. Boardman, “A General View of the Agriculture and Industry of the County of Kennebec, with Notes upon Its History and Natural History,” in Tenth Annual Report of the Secretary of the Maine Board of Agriculture (Augusta, ME: Stevens & Sayward, Printers to the State, 1865), 10: 137–38, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Murray 1989, 502–3, 508–9, 527, 535, view on Zotero; Green and Burke 1978, 78, view on Zotero; Emma Huntington Nason, Old Hallowell on the Kennebec (Augusta, ME: Press of Burleigh & Flynt, 1909), 86, view on Zotero; John H. Sheppard, Reminiscences of the Vaughan Family, and More Particularly of Benjamin Vaughan, LL.D. (Boston: David Clapp & Son, 1865), 16, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Timothy Dwight, Travels; in New-England and New-York, 4 vols. (New Haven: Timothy Dwight, 1821–22) view on Zotero.

- ↑ Alden Bradford, Biographical Notices of Distinguished Men in New England, (Boston: S.G. Simkins, 1842), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Robert Hallowell Gardiner, “Memoir of Benjamin Vaughan, M.D. and L.L.D.,” Collections of the Maine Historical Society, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Sheppard 1865, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Boardman 1865, view on Zotero.