Difference between revisions of "Pierre-Charles L’Enfant"

m |

m |

||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

From 1771 to 1776, Pierre-Charles L’Enfant studied at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris where his father, a painter specializing in landscapes and military subjects, was an instructor. Thereafter, he enlisted as a volunteer in the American Continental Army, serving primarily in the capacity of draftsman and surveyor. L’Enfant provided drawings for the American army’s first training manual and, while stationed at Valley Forge, drew a portrait of General [[George Washington]], who became an influential supporter of L’Enfant’s post-military career.<ref>Philander D. Chase, ed., ''The Papers of George Washington'', Revolutionary War Series, 90 vols. (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2008), 17:129, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/DN4FXZTM, view on Zotero]; Scott W. Berg, ''Grand Avenues : The Story of the French Visionary Who Designed Washington, DC'' (New York : Pantheon Books, 2007), 19–47, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/JME5Z7QW view on Zotero]; H. Paul Caemmerer, ''Pierre Charles L’Enfant, Planner of the City Beautiful, The City of Washington'' (Washington, DC: National Republic Publishing Company, 1950), 1–67, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/PUW9KRFB view on Zotero].</ref> L’Enfant had attained the rank of Captain of Engineers by the time of the British surrender in 1781. The following year, at the request of the French ambassador, [[George Washington|Washington]] sent L’Enfant to Philadelphia (then the U.S. capital) to design a colonnaded [[pavilion]] for dancing and other entertainments in honor of the birth of an heir to Louis XVI. According to Benjamin Rush, the surrounding grounds were “cut into beautiful [[walk]]s and divided with cedar and pine branches into artificial [[grove]]s.”<ref>Caemmerer 1950, 87–88, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/PUW9KRFB view on Zotero]; see also Sally Webster, “Pierre-Charles L’Enfant and the Iconography of Independence,” ''Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide'' 7 (2008), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/WUICCGFC view on Zotero].</ref> L’Enfant established a successful civil engineering practice in New York City, which became the seat of the federal government in 1785, and was celebrated for his efficient and elegant renovation of the old city hall, where the first United States Congress met and [[George Washington|Washington]] was inaugurated as president in 1789.<ref>Berg 2007, 64–70, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/JME5Z7QW view on Zotero]; Caemmerer 1950, 108–18, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/PUW9KRFB view on Zotero].</ref> | From 1771 to 1776, Pierre-Charles L’Enfant studied at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris where his father, a painter specializing in landscapes and military subjects, was an instructor. Thereafter, he enlisted as a volunteer in the American Continental Army, serving primarily in the capacity of draftsman and surveyor. L’Enfant provided drawings for the American army’s first training manual and, while stationed at Valley Forge, drew a portrait of General [[George Washington]], who became an influential supporter of L’Enfant’s post-military career.<ref>Philander D. Chase, ed., ''The Papers of George Washington'', Revolutionary War Series, 90 vols. (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2008), 17:129, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/DN4FXZTM, view on Zotero]; Scott W. Berg, ''Grand Avenues : The Story of the French Visionary Who Designed Washington, DC'' (New York : Pantheon Books, 2007), 19–47, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/JME5Z7QW view on Zotero]; H. Paul Caemmerer, ''Pierre Charles L’Enfant, Planner of the City Beautiful, The City of Washington'' (Washington, DC: National Republic Publishing Company, 1950), 1–67, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/PUW9KRFB view on Zotero].</ref> L’Enfant had attained the rank of Captain of Engineers by the time of the British surrender in 1781. The following year, at the request of the French ambassador, [[George Washington|Washington]] sent L’Enfant to Philadelphia (then the U.S. capital) to design a colonnaded [[pavilion]] for dancing and other entertainments in honor of the birth of an heir to Louis XVI. According to Benjamin Rush, the surrounding grounds were “cut into beautiful [[walk]]s and divided with cedar and pine branches into artificial [[grove]]s.”<ref>Caemmerer 1950, 87–88, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/PUW9KRFB view on Zotero]; see also Sally Webster, “Pierre-Charles L’Enfant and the Iconography of Independence,” ''Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide'' 7 (2008), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/WUICCGFC view on Zotero].</ref> L’Enfant established a successful civil engineering practice in New York City, which became the seat of the federal government in 1785, and was celebrated for his efficient and elegant renovation of the old city hall, where the first United States Congress met and [[George Washington|Washington]] was inaugurated as president in 1789.<ref>Berg 2007, 64–70, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/JME5Z7QW view on Zotero]; Caemmerer 1950, 108–18, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/PUW9KRFB view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| − | In July 1790, Congress authorized the building of a new capital city on the Potomac River. L’Enfant had already written to [[George Washington|Washington]] the previous year asking to design “the Foundation of a city which is to become the Capital of this vast Empire.”<ref>Caemmerer 1950, 127, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/PUW9KRFB view on Zotero].</ref> Duly appointed to survey and map the Federal territory, L’Enfant developed a visionary plan for a great metropolis. Drawing on his experience as a military engineer and borrowing ideas from the maps of various European cities provided to him by [[Thomas Jefferson]], he reinterpreted Old World conventions according to American ideals.<ref>Berg 2007, 105–13, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/JME5Z7QW view on Zotero]; Kirk Savage, ''Monument Wars: Washington, DC, the National Mall, and the Transformation of the Memorial Landscape'' (Berkeley | + | In July 1790, Congress authorized the building of a new capital city on the Potomac River. L’Enfant had already written to [[George Washington|Washington]] the previous year asking to design “the Foundation of a city which is to become the Capital of this vast Empire.”<ref>Caemmerer 1950, 127, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/PUW9KRFB view on Zotero].</ref> Duly appointed to survey and map the Federal territory, L’Enfant developed a visionary plan for a great metropolis. Drawing on his experience as a military engineer and borrowing ideas from the maps of various European cities provided to him by [[Thomas Jefferson]], he reinterpreted Old World conventions according to American ideals.<ref>Berg 2007, 105–13, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/JME5Z7QW view on Zotero]; Kirk Savage, ''Monument Wars: Washington, DC, the National Mall, and the Transformation of the Memorial Landscape'' (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 29–30, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/WNN7I268 view on Zotero]; Pamela Scott, “‘This Vast Empire’: The Iconography of the Mall, 1791–1848,” in ''The Mall in Washington'', ed. Richard Longstreth, Studies in the History of Art, Center for Advanced Studies in the Visual Arts, Symposium Papers, XIV (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1991), 37–45, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/N4WS8QU7 view on Zotero]; Therese O’Malley, “Art and Science in American Landscape Architecture: The National Mall, Washington, DC 1791–1852" (PhD diss., University of Pennsylvania, 1989), 26–48, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/TQVME883 view on Zotero]. J. L. Sibley Jennings Jr., “Artistry as Design: L’Enfant’s Extraordinary City,” ''Quarterly Journal of the Library of Congress'' 36 (1979): 231–37, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/TC3E674S view on Zotero]; Caemmerer 1950, 147, 149, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/PUW9KRFB view on Zotero].</ref> Exploiting the existing topography, L’Enfant reserved the most commanding positions for “Grand Edifices” (principally, the “Congress House” and “President’s House”) and “Grand [[Square]]s.” He connected these focal points by means of thirteen diagonally radiating [[avenue]]s representative of the original colonies. The long [[vista]]s were to be punctuated by a series of landscaped circles and [[square]]s ornamented with [[fountain]]s, [[column]]s, [[obelisk]]s, and other monuments in memory of those who had contributed to the nation’s liberty and independence. Each of the states of the union was to take responsibility for “improving” one of the [[square]]s as an expression of its distinct identity. An underlying network of intersecting streets, laid out in an orthogonal gridiron pattern, provided the connective tissue that unified the capital [Fig. 1.]<ref>Richard W. Stephenson, ''“A Plan Whol[l]y New”: Pierre Charles L’Enfant’s Plan of the City of Washington'' (Washington, DC: Library of Congress, 1993), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/Q3WX7W32 view on Zotero]; Caemmerer 1950, 150–65, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/PUW9KRFB view on Zotero]; Herman Kahn and Pierre L’Enfant, “Appendix to Pierre L’Enfant’s Letter to the Commissioners May 30, 1800,” ''Records of the Columbia Historical Society'' 44/45 (1942/43): 191–213, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/6FSVS97H view on Zotero].</ref> |

A succession of clashes with the commissioners overseeing L’Enfant’s work resulted in his dismissal in 1792.<ref>Caemmerer 1950, 169–215, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/PUW9KRFB view on Zotero].</ref> Nevertheless, his plan for the city of Washington remained a touchstone for the capital’s development into the late 20th century.<ref>Michael Bednar, ''L’Enfant’s Legacy: Public Open Spaces in Washington, DC'' (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/92VCHXR9 view on Zotero]; O’Malley 1989, 174, 184, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/TQVME883 view on Zotero]; Jennings 1979, 242–62, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/PUW9KRFB view on Zotero].</ref> L’Enfant worked on a number of other projects that ended abortively as a result of their outsize ambition and expense, as well as the architect’s prickly personality. These include the city plan and hydraulic system for Paterson, New Jersey (1793), [[Robert Morris]]’s mansion in Philadelphia (1794–96), Fort Mifflin on the Delaware (1793–95), and Fort Washington on the Potomac (1814).<ref>Ryan K. Smith, ''Robert Morris’s Folly: The Architectural and Financial Failures of an American Founder'' (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014), 60–201, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/ZKNMARKC view on Zotero]; Russell I. Fries, “European vs. American Engineering: Pierre Charles L’Enfant and the Water Power System of Paterson, NJ,” ''Northeast Historical Archaeology'' 4 (1974): 68–70, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/II6KF9NI view on Zotero].</ref> | A succession of clashes with the commissioners overseeing L’Enfant’s work resulted in his dismissal in 1792.<ref>Caemmerer 1950, 169–215, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/PUW9KRFB view on Zotero].</ref> Nevertheless, his plan for the city of Washington remained a touchstone for the capital’s development into the late 20th century.<ref>Michael Bednar, ''L’Enfant’s Legacy: Public Open Spaces in Washington, DC'' (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/92VCHXR9 view on Zotero]; O’Malley 1989, 174, 184, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/TQVME883 view on Zotero]; Jennings 1979, 242–62, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/PUW9KRFB view on Zotero].</ref> L’Enfant worked on a number of other projects that ended abortively as a result of their outsize ambition and expense, as well as the architect’s prickly personality. These include the city plan and hydraulic system for Paterson, New Jersey (1793), [[Robert Morris]]’s mansion in Philadelphia (1794–96), Fort Mifflin on the Delaware (1793–95), and Fort Washington on the Potomac (1814).<ref>Ryan K. Smith, ''Robert Morris’s Folly: The Architectural and Financial Failures of an American Founder'' (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014), 60–201, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/ZKNMARKC view on Zotero]; Russell I. Fries, “European vs. American Engineering: Pierre Charles L’Enfant and the Water Power System of Paterson, NJ,” ''Northeast Historical Archaeology'' 4 (1974): 68–70, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/II6KF9NI view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

Revision as of 18:24, October 3, 2018

Pierre-Charles L’Enfant (August 2, 1754–June 14, 1825) was a French architect, civil engineer, and urban designer best known for his plan of 1791 of the nations capital city of Washington, DC.

History

From 1771 to 1776, Pierre-Charles L’Enfant studied at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris where his father, a painter specializing in landscapes and military subjects, was an instructor. Thereafter, he enlisted as a volunteer in the American Continental Army, serving primarily in the capacity of draftsman and surveyor. L’Enfant provided drawings for the American army’s first training manual and, while stationed at Valley Forge, drew a portrait of General George Washington, who became an influential supporter of L’Enfant’s post-military career.[1] L’Enfant had attained the rank of Captain of Engineers by the time of the British surrender in 1781. The following year, at the request of the French ambassador, Washington sent L’Enfant to Philadelphia (then the U.S. capital) to design a colonnaded pavilion for dancing and other entertainments in honor of the birth of an heir to Louis XVI. According to Benjamin Rush, the surrounding grounds were “cut into beautiful walks and divided with cedar and pine branches into artificial groves.”[2] L’Enfant established a successful civil engineering practice in New York City, which became the seat of the federal government in 1785, and was celebrated for his efficient and elegant renovation of the old city hall, where the first United States Congress met and Washington was inaugurated as president in 1789.[3]

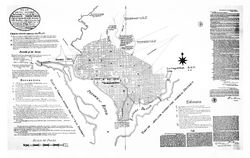

In July 1790, Congress authorized the building of a new capital city on the Potomac River. L’Enfant had already written to Washington the previous year asking to design “the Foundation of a city which is to become the Capital of this vast Empire.”[4] Duly appointed to survey and map the Federal territory, L’Enfant developed a visionary plan for a great metropolis. Drawing on his experience as a military engineer and borrowing ideas from the maps of various European cities provided to him by Thomas Jefferson, he reinterpreted Old World conventions according to American ideals.[5] Exploiting the existing topography, L’Enfant reserved the most commanding positions for “Grand Edifices” (principally, the “Congress House” and “President’s House”) and “Grand Squares.” He connected these focal points by means of thirteen diagonally radiating avenues representative of the original colonies. The long vistas were to be punctuated by a series of landscaped circles and squares ornamented with fountains, columns, obelisks, and other monuments in memory of those who had contributed to the nation’s liberty and independence. Each of the states of the union was to take responsibility for “improving” one of the squares as an expression of its distinct identity. An underlying network of intersecting streets, laid out in an orthogonal gridiron pattern, provided the connective tissue that unified the capital [Fig. 1.][6]

A succession of clashes with the commissioners overseeing L’Enfant’s work resulted in his dismissal in 1792.[7] Nevertheless, his plan for the city of Washington remained a touchstone for the capital’s development into the late 20th century.[8] L’Enfant worked on a number of other projects that ended abortively as a result of their outsize ambition and expense, as well as the architect’s prickly personality. These include the city plan and hydraulic system for Paterson, New Jersey (1793), Robert Morris’s mansion in Philadelphia (1794–96), Fort Mifflin on the Delaware (1793–95), and Fort Washington on the Potomac (1814).[9]

—Robyn Asleson

Texts

- L’Enfant, Pierre-Charles, March 11, 1791, in a letter to Thomas Jefferson, describing Washington, DC (quoted in Caemmerer 1950: 136)[10]

- “The remainder part of that ground towards Georgetown is more broken. It may afford pleasant seats, but, although the bank of the river between the two creeks can command as grand a prospect as any of the other spots, it seems to be less commendable for the establishment of a city, not only because the level surface it presents is but small, but because the hights from beyond Georgetown absolutely command the whole.”

- L’Enfant, Pierre-Charles, June 22, 1791, in a report to George Washington on his plans for Washington, DC (quoted in Caemmerer 1950: 151–53)[11]

- “. . . having first determined some principal points to which I wished making the rest subordinate I next made the distribution regular with streets at right angle north-south and east west but afterwards I opened others on various directions as avenues to and from every principal places, wishing by this not merely to contrast with the general regularity nor to afford a greater variety of pleasant seats and prospect as will be obtained from the advantageous ground over the which the avenues are mostly directed but principally to connect each part of the city with more efficacy by, if I may so express, making the real distance less from place to place in menaging on them a reisprocity of sight and making them thus seemingly connected promot a rapide stellement over the whole. . . .

- “. . . a canal being easy to open from the eastern branch and to be lead across the first settlement and carried toward the mouth of the [T]iber where it will again give an issue into the Potowmack and at a distance not to far off for to admit the boats from the grand navigation canal from getting in, will undoubtedly facilitate a conveyance most advantageous to trading Interest. . . .

- “I placed the three grand Departments of State contigous to the principle Palace and on the way leading to the Congressional House the gardens of the one together with the park and other improvement on the dependency are connected with the publique walk and avenue to the Congress house in a manner as most [must] form a whole as grand as it will be agreeable and convenient to the whole city which form [from] the distribution of the local [locale] will have an early access to this place of general resort and all along side of which may be placed play houses, room of assembly, accademies and all such sort of places as may be attractive to the learned and afford diversion to the idle. . . .

- “I propose in this map, of leting the [T]iber return in its proper channel by a fall which issuing from under the base of the Congress building may there form a cascade of forty feet heigh [sic] or more than one hundred waide [sic] which would produce the most happy effect in rolling down to fill up the canall [sic] and discharge itself in the Potowmack of which it would then appear as the main spring when seen through that grand and majestic avenue intersecting with the prospect from the palace at a point which being seen from both I have designated as the proper for to erect a grand equestrian figure.”

- L’Enfant, Pierre-Charles, August 19, 1791 describing his plans for Washington, DC (quoted in Caemmerer 1950: 157)[11]

- “The grand avenue connecting the palace and the Federal House will be magnificent, with the water of the cascade [falling] to the canal which will extend to the Potomac; as also the several squares which are intended for the Judiciary Courts, the National Bank, the grand Church, the play house, markets and exchange, offering a variety of situations unparallelled for beauty, suitable for every purpose, and in every point convenient, calculated to command the highest price at a sale.”

- L’Enfant, Pierre-Charles, January 4, 1792, from notes on “Plan of the City” describing Washington, DC (quoted in Caemmerer 1950: 163–65)[10]

- “I. The positions for the different Grand Edifices, and for the several Grand Squares or Areas of different shapes as they are laid down, were first determined on the most advantageous ground, commanding the most extensive prospects, and the better susceptible of such improvements as the various intents of the several objects may require. [Fig. 2]

- “II. Lines or Avenues of direct communication have been devised, to connect the separate and most distant objects with the principal, and to preserve through the whole a reciprocity of sight at the same time. Attention has been paid to the passing of those leading avenues over the most favorable ground for prospect and convenience.

- “III. North and South lines, intersected by others running due East and West, make the distribution of the city into streets, squares, etc. . . .

- “Every Grand transverse Avenue, and every principal divergent one, such as the communication from the President’s House to the Congress House etc. are 160 feet in breadth and thus divided:

- 10 feet of pavement on each side . . . . . . 20

- 30 feet of gravel walk planted

- with trees on each side . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 60

- 80 feet in the middle for carriage way . . 80

- 160 feet. . . .

- “B. An historic Column—also intended for a Mile or itinerary Column, from whose station (a mile from the Federal house) all distances of places throughout the Continent to be calculated.

- “C. A Naval itinerary Column, proposed to be erected to celebrate the first prize of a Navy and to stand a ready Monument to consecrate its progress and achievements. . . .

- “E. Five grand fountains intended with a constant spout of water. N. B. There are within the limits of the City above 25 good springs of excellent water abundantly supplied in the driest season of the year.

- “F. Grand Cascade, formed of water from the sources of the Tiber.

- “G. Public walk, being a square of 1200 feet, through which carriages may ascend to the upper Square of the Federal House.

- “H. Grand Avenue, 400 feet in breadth, and about a mile in length, bordered with gardens, ending in a slope from the houses on each side. This Avenue leads to Monument A and connects the Congress Garden with the

- “I. President’s park and the

- “K. well-improved field. . . .

- “M. . . . The Squares colored yellow, being fifteen in number, are proposed to be divided among the several States of the Union, for each of them to improve, or subscribe a sum additional to the value of the land; that purpose and the improvements around the Square to be completed in a limited time.

- “The center of each Square will admit of Statues, Columns, Obelisks, or any other ornament such as the different States may choose to erect: to perpetuate not only the memory of such individuals whose counsels or Military achievements were conspicuous in giving liberty and independence to this Country; but also those whose usefulness hath rendered them worthy of general imitation, to invite the youth of succeeding generations to tread in the paths of those sages, or heroes whom their country has thought proper to celebrate.

- “The situation of these Squares is such that they are the most advantageously and reciprocally seen from each other and as equally distributed over the whole City district, and connected by spacious avenues round the grand Federal Improvements and as contiguous to them, and at the same time as equally distant from each other, as circumstances would admit. The Settlements round those Squares must soon become connected.”

Images

Other Resources

Library of Congress Authority File

The Cultural Landscape Foundation

Notes

- ↑ Philander D. Chase, ed., The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, 90 vols. (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2008), 17:129, view on Zotero; Scott W. Berg, Grand Avenues : The Story of the French Visionary Who Designed Washington, DC (New York : Pantheon Books, 2007), 19–47, view on Zotero; H. Paul Caemmerer, Pierre Charles L’Enfant, Planner of the City Beautiful, The City of Washington (Washington, DC: National Republic Publishing Company, 1950), 1–67, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Caemmerer 1950, 87–88, view on Zotero; see also Sally Webster, “Pierre-Charles L’Enfant and the Iconography of Independence,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 7 (2008), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Berg 2007, 64–70, view on Zotero; Caemmerer 1950, 108–18, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Caemmerer 1950, 127, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Berg 2007, 105–13, view on Zotero; Kirk Savage, Monument Wars: Washington, DC, the National Mall, and the Transformation of the Memorial Landscape (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 29–30, view on Zotero; Pamela Scott, “‘This Vast Empire’: The Iconography of the Mall, 1791–1848,” in The Mall in Washington, ed. Richard Longstreth, Studies in the History of Art, Center for Advanced Studies in the Visual Arts, Symposium Papers, XIV (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1991), 37–45, view on Zotero; Therese O’Malley, “Art and Science in American Landscape Architecture: The National Mall, Washington, DC 1791–1852" (PhD diss., University of Pennsylvania, 1989), 26–48, view on Zotero. J. L. Sibley Jennings Jr., “Artistry as Design: L’Enfant’s Extraordinary City,” Quarterly Journal of the Library of Congress 36 (1979): 231–37, view on Zotero; Caemmerer 1950, 147, 149, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Richard W. Stephenson, “A Plan Whol[l]y New”: Pierre Charles L’Enfant’s Plan of the City of Washington (Washington, DC: Library of Congress, 1993), view on Zotero; Caemmerer 1950, 150–65, view on Zotero; Herman Kahn and Pierre L’Enfant, “Appendix to Pierre L’Enfant’s Letter to the Commissioners May 30, 1800,” Records of the Columbia Historical Society 44/45 (1942/43): 191–213, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Caemmerer 1950, 169–215, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Michael Bednar, L’Enfant’s Legacy: Public Open Spaces in Washington, DC (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006), view on Zotero; O’Malley 1989, 174, 184, view on Zotero; Jennings 1979, 242–62, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Ryan K. Smith, Robert Morris’s Folly: The Architectural and Financial Failures of an American Founder (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014), 60–201, view on Zotero; Russell I. Fries, “European vs. American Engineering: Pierre Charles L’Enfant and the Water Power System of Paterson, NJ,” Northeast Historical Archaeology 4 (1974): 68–70, view on Zotero.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Caemmerer 1950, view on Zotero.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedCaemmerer 1950