Difference between revisions of "Mount Auburn Cemetery"

m (spacing fix) |

m |

||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

==History== | ==History== | ||

[[File:0117.jpg|thumb|Fig. 1, Thomas Chambers, ''Mount Auburn Cemetery'', mid-19th century.]] | [[File:0117.jpg|thumb|Fig. 1, Thomas Chambers, ''Mount Auburn Cemetery'', mid-19th century.]] | ||

| − | Prior to the founding of Mount Auburn Cemetery [Fig. 1] in 1831, residents of New England were generally interred in graveyards associated with their respective churches; in Boston, these included the King’s Chapel, Old Granary, and Central Burying Grounds along the perimeter of the [[Common]], and Copp’s Hill Burying Ground in the North End. With the enormous growth of Boston’s population following the American Revolution, however, these sites were quickly overcrowded. Boston’s early [[burial ground|burying grounds]], with their disorganized jumble of headstones, came to be seen as an aesthetic blight on the developing city, and their close proximity to both residences and businesses was considered a public health hazard.<ref>Blanche M. G. Linden, ''Silent City on a Hill: Picturesque Landscapes of Memory and Boston’s Mount Auburn Cemetery'' (1989; repr., Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2007), 118–20, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/NJ7267GQ/q/linden view on Zotero]. See also David Charles Sloane, ''The Last Great Necessity: Cemeteries in American History'' (Baltimore: | + | Prior to the founding of Mount Auburn Cemetery [Fig. 1] in 1831, residents of New England were generally interred in graveyards associated with their respective churches; in Boston, these included the King’s Chapel, Old Granary, and Central Burying Grounds along the perimeter of the [[Common]], and Copp’s Hill Burying Ground in the North End. With the enormous growth of Boston’s population following the American Revolution, however, these sites were quickly overcrowded. Boston’s early [[burial ground|burying grounds]], with their disorganized jumble of headstones, came to be seen as an aesthetic blight on the developing city, and their close proximity to both residences and businesses was considered a public health hazard.<ref>Blanche M. G. Linden, ''Silent City on a Hill: Picturesque Landscapes of Memory and Boston’s Mount Auburn Cemetery'' (1989; repr., Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2007), 118–20, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/NJ7267GQ/q/linden view on Zotero]. See also David Charles Sloane, ''The Last Great Necessity: Cemeteries in American History'' (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991), 45, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/972MSSSH/q/sloane view on Zotero], and James R. Cothran and Erica Danylchak, ''Grave Landscapes: The Nineteenth-Century Rural Cemetery Movement'' (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2018), 37–38, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/THCP4J2V view on Zotero].</ref> |

In the mid-1820s Boston mayor Josiah Quincy passed the Ordinance on the Burial of the Dead, which forbade further interments at the King’s Chapel and Old Granary Burying Grounds and better regulated other burials within city limits.<ref>Sloane 1991, 44–45, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/972MSSSH/q/sloane view on Zotero]; Linden 2007, 130, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/NJ7267GQ/q/linden view on Zotero]; and Cothran and Danylchak 2018, 38, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/THCP4J2V view on Zotero]. For the text of the ordinance, see ''The Charter of the City of Boston, and Ordinances Made and Established by the Mayor, Aldermen, and Common Council'' (Boston: True and Greene, 1827), 182–87, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/8Z9RGAV2 view on Zotero].</ref> About the same time, according to historian Blanche Linden, a growing movement for a “rural” cemetery emerged. In 1823 Dr. John Coffin, a fellow of the Massachusetts Medical Society, published a pamphlet arguing that bodies should be interred in a pastoral setting where they could “naturally” return to the earth, and in 1825 Jacob Bigelow, a professor of botany at Harvard, established an association for creating a cemetery that situated burial plots within a carefully cultivated landscape.<ref>Linden 2007, 128–35, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/NJ7267GQ/q/linden view on Zotero].</ref> | In the mid-1820s Boston mayor Josiah Quincy passed the Ordinance on the Burial of the Dead, which forbade further interments at the King’s Chapel and Old Granary Burying Grounds and better regulated other burials within city limits.<ref>Sloane 1991, 44–45, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/972MSSSH/q/sloane view on Zotero]; Linden 2007, 130, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/NJ7267GQ/q/linden view on Zotero]; and Cothran and Danylchak 2018, 38, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/THCP4J2V view on Zotero]. For the text of the ordinance, see ''The Charter of the City of Boston, and Ordinances Made and Established by the Mayor, Aldermen, and Common Council'' (Boston: True and Greene, 1827), 182–87, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/8Z9RGAV2 view on Zotero].</ref> About the same time, according to historian Blanche Linden, a growing movement for a “rural” cemetery emerged. In 1823 Dr. John Coffin, a fellow of the Massachusetts Medical Society, published a pamphlet arguing that bodies should be interred in a pastoral setting where they could “naturally” return to the earth, and in 1825 Jacob Bigelow, a professor of botany at Harvard, established an association for creating a cemetery that situated burial plots within a carefully cultivated landscape.<ref>Linden 2007, 128–35, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/NJ7267GQ/q/linden view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

Revision as of 14:10, September 20, 2018

Mount Auburn Cemetery was founded by Harvard botanist Jacob Bigelow and the Massachusetts Horticultural Society, and was the first cemetery to be laid out according the principles of English landscape design. Its establishment marked the beginning of the rural cemetery movement in the United States.

Overview

Alternate Names: Sweet Auburn

Site Dates: 1831–present

Site Owner: Massachusetts Horticultural Society (1831−35); Proprietors of the Cemetery of Mount Auburn (1835−present)

Associated People: Jacob Bigelow (1787−1879; original proponent of the cemetery); H. A. S. Dearborn (1783−1851; designer); Alexander Wadsworth (1806−1898; surveyor)

Location Cambridge, MA

Condition: extant

View on Google maps

History

Prior to the founding of Mount Auburn Cemetery [Fig. 1] in 1831, residents of New England were generally interred in graveyards associated with their respective churches; in Boston, these included the King’s Chapel, Old Granary, and Central Burying Grounds along the perimeter of the Common, and Copp’s Hill Burying Ground in the North End. With the enormous growth of Boston’s population following the American Revolution, however, these sites were quickly overcrowded. Boston’s early burying grounds, with their disorganized jumble of headstones, came to be seen as an aesthetic blight on the developing city, and their close proximity to both residences and businesses was considered a public health hazard.[1]

In the mid-1820s Boston mayor Josiah Quincy passed the Ordinance on the Burial of the Dead, which forbade further interments at the King’s Chapel and Old Granary Burying Grounds and better regulated other burials within city limits.[2] About the same time, according to historian Blanche Linden, a growing movement for a “rural” cemetery emerged. In 1823 Dr. John Coffin, a fellow of the Massachusetts Medical Society, published a pamphlet arguing that bodies should be interred in a pastoral setting where they could “naturally” return to the earth, and in 1825 Jacob Bigelow, a professor of botany at Harvard, established an association for creating a cemetery that situated burial plots within a carefully cultivated landscape.[3]

Despite the crowding and public health concerns of city burials, Bigelow’s proposal for a rural cemetery encountered some resistance. Many Bostonians believed rural interment was appropriate only for social outcasts; they also feared burial outside the city limits might lead to the theft of bodies by “resurrection men”—body snatchers who stole corpses for medical study.[4] Bigelow and his associates argued that a pastoral setting would allow for a more socially productive, and more American, type of mourning. Graves situated in a beautiful landscape would highlight the naturalness of death and reduce the anxiety and fear associated with the end of life [Fig. 2]. Moreover, a rural setting would recall the original landscape of New England, inviting the general public to connect to the country’s past and engage with ideas of continuity and posterity.[5]

The development of Mount Auburn Cemetery began in earnest in 1830, with the coordination of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society, founded only a year earlier. The plan was to incorporate in one expansive site a rural burying ground, or “garden of graves,” alongside an experimental garden that together could foster “historical and horticultural consciousness.”[6] The land Bigelow’s association purchased for the cemetery’s construction—Stone’s Woods or “Sweet Auburn,” 72 acres of rolling, wooded hills across the Charles River from Boston—had long been a place of pastoral respite for locals, including Harvard students. Writing in his journal in 1824, Ralph Waldo Emerson observed that “there is some wild land called Sweet Auburn . . . [and] the students will go in bands over a flat sandy road & in summer evenings the woods are full of them.”[7] Not surprisingly the connection between nature, culture, and the divine that drove the founding of Mount Auburn Cemetery would also shape the views of such Transcendentalists as Emerson.

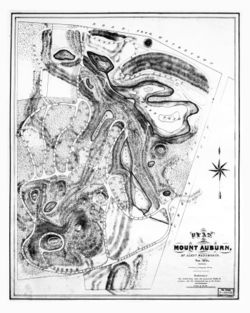

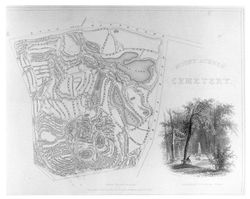

The layout of Mount Auburn began in 1831 and was overseen by the first president of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society, H. A. S. Dearborn, aided by Alexander Wadsworth [Fig. 3]. Dearborn drew on the design of the Parisian cemetery Père Lachaise—the world’s first garden or “ornamental” cemetery—and laid out the grounds according to the natural style of English landscape design.[8] He incorporated winding gravel paths, wide planted borders, and small ponds among the rolling hills of the site, which created the variety of views so essential to the English garden.[9] It was also a means of keeping burial lots properly distanced from one another. These were sold by subscription, mostly to families, but also to several local organizations, such as Harvard College and the Tremont House, a Boston hotel. The few corporate lots were intended for deceased students and visitors whose bodies could not be shipped home.[10]

Lingering concerns about a pastoral cemetery, particularly regarding the security of graves, did not seem to limit interest in Mount Auburn, but the cemetery faced other challenges. Revenue generated by the sale of lots failed to cover the cost of establishing an experimental garden, leading to the Massachusetts Historical Society’s withdrawal from the project in 1835 and the chartering of a new, charitable organization–the Proprietors of the Cemetery of Mount Auburn–to oversee the site.[11] Another challenge was the behavior of some of Mount Auburn’s visitors: although originally designed as a fully public space, the cemetery was enclosed by fences in 1833 to deter vandalism, and public visitation was limited to daylight hours. A system of fines was established to counter destructive behavior toward plants, trees, and burial markers.[12]

Mount Auburn also came under scrutiny for its apparent elitism. The prohibitive costs of the average 300-square-foot lot—about $60—were thought by some to undermine the cemetery’s accessibility and openness.[13] Early critics saw the cemetery less as a site of moral education and more as an aggrandizement of New England’s elite, a number of whom marked their burial sites with imposing monuments. Although the cemetery’s board encouraged simplicity in burial markers—preferring obelisks, tombs, and sarcophagi over more elaborate constructions—the lot of the wealthy merchant and philanthropist Samuel Appleton boasted a 12-by-6-foot Grecian temple made of Italian marble, for which he paid the enormous sum of $10,000 [Fig. 4].[14] For those who could not afford the expense of a standard lot, Mount Auburn Cemetery offered 160 individual graves that could be purchased for $10 each, though this accommodation did not fully quash the view of rural interment as a luxury unattainable for many.[15]

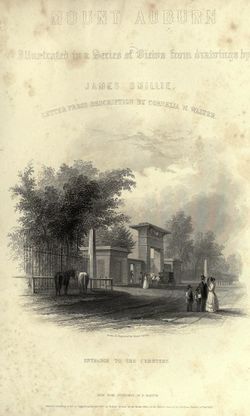

Many of Mount Auburn’s visitors were neither proprietors nor friends and family of people interred at the site; despite the restrictions placed on the public, the cemetery functioned as “a place of general resort and interest, as well to strangers as to citizens,” one whose “shades and paths, ornamented with monumental structures, of various beauty and elegance, have already . . . awakened a deep moral sensibility in many a pious bosom.”[16] A market for Mount Auburn guidebooks quickly developed, beginning with The Picturesque Companion, and Visitor’s Guide, through Mount Auburn (1839) and perhaps reaching its apogee with Cornelia W. Walter’s Mount Auburn Illustrated (1847), which was frequently reprinted over the next decade. In her book Walter, a former editor of the Boston Transcript, provided readers a brief history of the cemetery and an architectural tour through its more celebrated monuments, illustrated by the prolific engraver James Smillie. The volume begins with a description of the imposing Egyptian-style portal at the cemetery’s entrance [Fig. 5] and passes by a variety of architectural styles—the neo-Gothic design of the Chapel and the classicizing temple on Samuel Appleton’s lot—before concluding with a view from Mount Auburn’s highest point, the “mount” of its name.

Walter’s guidebook, organized by prospects both of and from Mount Auburn, offsets manmade structures against the site’s pastoral setting to underscore the restorative qualities of nature. The mount of Mount Auburn, she observed, provides a view of “the numerous spires of the near city of Boston,” which—framed by the Charles River and the “varied undulations of the hills and dales, the tranquil lakes, and the deep shadows of the groves”—metamorphoses from an overcrowded metropolis into an image of solemnity and repose [Fig. 6].[17] The effect she described is the very one articulated by Mount Auburn’s promoters, who had intended to articulate a harmonious accord between life and death, culture and nature, history and horticulture.

The creation of Mount Auburn Cemetery, along with the reframing of death and decay as wholly natural processes, permanently altered Americans’ practices of burial and mourning and led to development of rural cemeteries across the United States. Between 1831 and 1873, more than 175 such cemeteries were established, including Philadelphia’s celebrated Laurel Hill (1838) and Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery (1838).[18]

—Elizabeth Athens

Texts

- Story, Joseph, September 24, 1831, describing Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, MA (1831: 16–17, 29)[19]

- “A rural Cemetery seems to combine in itself all the advantages, which can be proposed to gratify human feelings, or tranquillize human fears; to secure the best religious influences, and to cherish all those associations, which cast a cheerful light over the darkness of the grave.

- “And what spot can be more appropriate than this for such a purpose? Nature seems to point it out with significant energy, as the favorite retirement for the dead. There are around us all the varied features of her beauty and grandeur—the forest-crowned height; the abrupt acclivity; the sheltered valley; the deep glen; the grassy glade; and the silent grove. Here are the lofty oak, the beech, that ‘wreaths its old fantastic roots so high,’ the rustling pine, and the drooping willow; —the tree, that sheds its pale leaves with every autumn, a fit emblem of our own transitory bloom; and the evergreen, with its perennial shoots, instructing us, that ‘the wintry blast of death kills not the buds of virtue.’ Here is the thick shrubbery to protect and conceal the new-made grave; and there is the wild-flower creeping along the narrow path, and planting its seeds in the upturned earth. All around us there breathes a solemn calm, as if we were in the bosom of a wilderness, broken only by the breeze as it murmurs through the tops of the forest, or by the notes of the warbler pouring forth his matin or his evening song. . . .

- “The grounds of the Cemetery have been laid out with intersecting avenues, so as to render every part of the wood accessible. These avenues are curved and variously winding in their course, so as to be adapted to the natural inequalities of the surface. By this arrangement, the greatest economy of the land is produced, combining at the same time the picturesque effect of landscape gardening. Over the more level portions, the avenues are made twenty feet wide, and are suitable for carriage roads.”

- Dearborn, H. A. S., 30 September 1831, describing Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, MA (quoted in Ward 1831: 48)[20]

- “The nurseries may be established, the departments for culinary vegetables, fruit, and ornamental trees, shrubs and flowers, laid out and planted, a green house built, hot-beds formed, the small ponds and morasses converted into picturesque sheets of water, and their margins diversified by clumps and belts of our most splendid native flowering trees, and shrubs, requiring a soil thus constituted for their successful cultivation, while their surface may be spangled with the brilliant blossoms of Nymphae, and the other beautiful tribes of aquatic plants.”

- Dearborn, H. A. S., 1832, describing Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, MA (quoted in Harris 1832: 63–65, 67–68, 72, 80)[21]

- “With the Experimental Garden it is recommended to unite a Rural Cemetery; for the period is not distant, when all the burial grounds within the city will be closed, and others must be formed in the country,—the primitive and only proper location. There the dead may repose undisturbed, through countless ages. There can be formed a public place of sepulture, where monuments can be erected to our illustrious men, whose remains, thus far, have unfortunately been consigned too obscure and isolated tombs, instead of being collected within one common depository, where their great deeds might be perpetuated and their memories cherished by succeeding generations. Though dead, they would be eternal admonitors to the living,—teaching them the way which leads to national glory and individual renown. . . .

- “For the accommodation of the Garden of Experiment and Cemetery, at least seventy acres of land are deemed necessary; and in making the selection of a site, it was very important that from forty to fifty acres should be well or partially covered with forest trees and shrubs, which could be appropriated for the latter establishment; and that it should present all possible varieties of soil, common in the vicinity of Boston; be diversified by hills, valleys, plains, brooks, and low meadows and bogs, so as to afford proper localities for every kind of tree and plant, that will flourish in this climate;—be near to some large stream or river; and easy of access by land and water; but still sufficiently retired.

- “To realize these advantages it is proposed, that a tract of land called ‘Sweet Auburn,’ situated in Cambridge, should be purchased. As a large portion of the ground is now covered with trees, shrubs, and wild flowering plants, avenues and walks may be made through them, in such a manner as to render the whole establishment interesting and beautiful, at a small expense, and within a few years; and ultimately offer an example of landscape or picturesque gardening, in conformity to the modern style of laying out grounds, which will be highly creditable to the Society. . . .

- “The establishment of rural cemeteries similar to that of Pere La Chaise, has often been the subject of conversation in this country, and frequently adverted to by the writers in our scientific and literary publications. . . .

- “That part of the land which has been recommended for a Cemetery may be circumvallated by a spacious avenue bordered by trees, shrubbery, and perennial flowers; rather as a line of demarcation than of disconnexion; for the ornamental grounds of the Garden should be apparently blended with those of the Cemetery, and the walks of each so intercommunicate as to afford an uninterrupted range over both, as one common domain.

- “Among the hills, glades, and dales, which are now covered with evergreen and deciduous trees and shrubs, may be selected sites for isolated graves, and tombs, and these, being surmounted with columns, obelisks, and other appropriate monuments of granite and marble, may be rendered interesting specimens of art; they will also vary and embelish the scenery embraced within the scope of the numerous sinuous avenues, which may be felicitously opened in all directions and to a vast extent, from the diversified and picturesque features which the topography of the tract of land presents. . . .

- “The approach from the main road leading to Watertown, was by a broad and umbrageous avenue to the foot of the hill, which closes the dale of consecration on the north. . . . In the rear, under the shade of a stately grove of walnuts, where the main avenue divides and gracefully sweeps round the lofty hills to the east and west, the company [attending the consecration] descended from their carriages, and entered the secluded and romantic silvan theatre, by two foot paths, which wound through lonely vales of arching verdure. . . .

- “The upper Garden Pond has been excavated, to a sufficient depth to afford a constant sheet of water, with a fall at the outlet of three feet, and being embanked, avenues with a border of six feet, for shrubs and flowers, have been made all round it. . . .

- “Arrangements have been made for excavating, to a greater depth, Forest and Consecration-Dell Ponds, and surrounding them by embellished pathways, like those of Garden-Pond, and for cleaning the eastern portion of Garden and of Meadow Ponds, of bushes and weeds; all which will be done during the winter, that season being the most favorable for such work.”

- Anonymous, 1839, describing Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, MA (1839: 3)[22]

- ”The celebrity attained by Mount Auburn, pronounced by European travellers the most beautiful Cemetery in existence, and which, perhaps, without assuming too much, may be called the Père la Chaise of America,—the extraordinary natural loveliness of the spot,—the admirable character of the establishment which is there maintained,—the fact that this was the first conspicuous example of the kind in our country.”

- Anonymous, 1839, describing Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, MA (1839: 47–48)[23]

- “That part of the land which has been recommended for a CEMETERY, may be circumvallated by a spacious avenue, bordered by trees, shrubbery and perennial flowers,—rather as a line of demarcation, than of disconnexion,—for the ornamental grounds of the GARDEN should be apparently blended with those of the Cemetery, and the walks of each so intercommunicate, as to afford an uninterrupted range over both, as one common domain.”

- Buckingham, James Silk, 1841, describing Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, MA (1841: 2:382)[24]

- “A comparison has been often made between the Père la Chaise of Paris and the Mount Auburn of Boston, and the similarity of their situation and their purpose naturally forces this comparison on the mind. Having seen both, I may venture to offer an opinion on this subject, with great deference, however, to those who may think otherwise. In many respects, then, I think Mount Auburn superior to Père la Chaise. Its natural scenery of hill and dale, of river, lake, and forest-trees, with other surrounding objects, presents a combination which is not to be found in the cemetery of Paris, and which is far more in harmony with the repose of the dead than the most sumptuous monuments, without these combinations, can be. In this last respect Père la Chaise is perhaps unrivalled.”

- Walter, Cornelia W., 1847, describing Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, MA (1847: 14)[25]

- “The avenues are winding in their course and exceedingly beautiful in their gentle circuits, adapted picturesquely to the inequalities of the surface of the ground, and producing charming landscape effects from this natural arrangement, such as could never be had from straightness or regularity. . . .

- “The gateway of Mount Auburn opened from what is known as the north boundary line of the Cemetery. This avenue forms a wide carriage-road, and is one of the most beautiful openings ever improved for such a purpose. With the exception of the necessary grading, levelling, and cutting done of the brushwood, and the planting of a few trees, it has been left as Nature has made it. On either side it is overshadowed by the foliage of forest-trees, firs, pines, and other evergreens; and here you first begin to see the monuments starting up from the surrounding verdure, like bright remembrances from the heart of earth” [Fig. 7].

- Cleaveland, Nehemiah, 1847, describing Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, MA (quoted in Walter 1847: 20)[26]

- “In 1844, the increasing funds of the corporation justified a new expenditure for the plain but massy iron fence which encloses the front of the Cemetery. This fence is ten feet in height, and supported on granite posts extending four feet into the ground. It measures half a mile in length, and will, when completed, effectually preserve the Cemetery inviolate from any rude intrusion. The cost of the gateway was about $10,000—the fence, $15,000.

- “A continuation of the iron fence on the easterly side is now under contract, and a strong wooden palisade is, as we learn, to be erected on the remaining boundary during the present year.”

- Downing, Alexander Jackson, July 1849, “Public Cemeteries and Public Gardens” (Horticulturist 4: 9–10)[27]

- “Indeed, in the absence of great public gardens, such as we must surely one day have in America, our rural cemeteries are doing a great deal to enlarge and educate the popular taste in rural embellishment. They are for the most part laid out with admirable taste; they contain the greatest variety of trees and shrubs to be found in the country, and several of them are kept in a manner seldom equalled in private places. . . .

- “The character of each of the three great cemeteries is essentially distinct. Greenwood, the largest, and unquestionably the finest, is grand, dignified, and park-like. It is laid out in a broad and simple style, commands noble ocean views, and is admirably kept. Mount Auburn is richly picturesque, in its varied hill and dale, and owes its charm mainly to this variety and intricacy of sylvan features. Laurel Hill is a charming pleasure-ground, filled with beautiful and rare shrubs and flowers; at this season, a wilderness of roses, as well as fine trees and monuments.”

- Loudon, J. C. (John Claudius), 1850, describing cemeteries in America (1850: 333)[28]

- “857. Cemeteries. . . .

- “A public cemetery was formed in 1831 at Mount Auburn, about three miles from Boston, and is easily approached either by the road, or the river which washes its borders. . . . ‘This romantic and picturesque cemetery,’ says Dr. Mease, ‘is the fashionable place of interment with the people of Boston.’ . . .

Images

Map

Other Resources

Notes

- ↑ Blanche M. G. Linden, Silent City on a Hill: Picturesque Landscapes of Memory and Boston’s Mount Auburn Cemetery (1989; repr., Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2007), 118–20, view on Zotero. See also David Charles Sloane, The Last Great Necessity: Cemeteries in American History (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991), 45, view on Zotero, and James R. Cothran and Erica Danylchak, Grave Landscapes: The Nineteenth-Century Rural Cemetery Movement (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2018), 37–38, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Sloane 1991, 44–45, view on Zotero; Linden 2007, 130, view on Zotero; and Cothran and Danylchak 2018, 38, view on Zotero. For the text of the ordinance, see The Charter of the City of Boston, and Ordinances Made and Established by the Mayor, Aldermen, and Common Council (Boston: True and Greene, 1827), 182–87, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Linden 2007, 128–35, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Linden 2007, 161, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Sloane 1991, 45, view on Zotero, and Linden 2007, 141, 145, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Sloane 1991, 46, view on Zotero, and Linden 2007, 145, view on Zotero. The phrase “Garden of Graves” was the title of an essay on Mount Auburn by John Pierpont, published in Nathaniel Parker Willis, ed., The Token (Boston: S. G. Goodrich, 1832), 374–90, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Edward Waldo Emerson and Waldo Emerson Forbes, eds., Journals of Ralph Waldo Emerson, 1820–24 (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1909), 350, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Sloane 1991, 46, 49–50, view on Zotero, and Linden 2007, 173–74, view on Zotero. As Linden notes, Alexander Wadsworth surveyed the site but the design was primarily Dearborn’s. For more on the design and architecture of Père Lachaise, see Richard A. Etlin, The Architecture of Death: The Transformation of the Cemetery in Eighteenth-Century Paris (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1984), 310–35, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Linden 2007, 147, 155–59, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Cornelia W. Walter, Mount Auburn Illustrated (New York: R. Martin, 1847), 68, view on Zotero, and Linden 2007, 164, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Cothran and Danylchak 2018, 38, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Linden 2007, 167, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Sloane 1991, 53, view on Zotero, and Linden 2007, 163, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Sloane 1991, 53, view on Zotero, and Linden 2007, 186–87, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Sloane 1991, 54, view on Zotero, and Linden 2007, 163, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Joseph Story, October 17, 1834, Records of Committees, quoted in Linden 2007, 168, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Walter 1847, 112–13, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Sloane 1991, 63, view on Zotero; see also Appendix C in Cothran and Danylchak 2018, 231–39, which provides a select list of rural cemeteries organized by name, date, and location, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Joseph Story, An Address Delivered on the Dedication of the Cemetery at Mount Auburn (Boston: Joseph T. and Edwin Buckingham, 1831), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Malthus Ward, An Address Pronounced Before the Massachusetts Horticultural Society (Boston: J. T. & E Buckingham, 1831), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thaddeus William Harris, A Discourse Delivered Before the Massachusetts Horticultural Society on the Celebration of its Fourth Anniversary, October 3, 1832 (Cambridge, MA: E. W. Metcalf, 1832), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Anonymous, The Picturesque Pocket Companion and Visitor’s Guide through Mount Auburn (Boston: Otis, Broader, 1839), view on Zotero.

- ↑ The Picturesque Pocket Companion 1839, view on Zotero.

- ↑ James Silk Buckingham, America, Historical, Statistical, and Descriptive, 2 vols. (New York: Harper, 1841), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Walter 1847, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Walter 1847, view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. Downing, “Public Cemeteries and Public Gardens,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 4, no. 1 (July 1849): 9–12, view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening, new ed., corrected and improved (London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans, 1850), view on Zotero.