Difference between revisions of "Drive"

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

As the term itself implies, a drive was part of the processional experience of the natural or [[picturesque]] landscape. <ref>Much of Stephen Daniels’s discussion of the relation of Humphry Repton’s landscape design to road transportation in England is relevant to American landscape practice in the sec.ond quarter of the nineteenth century, although Repton himself does not appear to have used the term “drive” to refer to a road. See Daniels, “On the Road with Humphry Repton,” ''Journal of Garden History'' 16, no. 3 (autumn 1996): 170–91, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/3GKTB645 view on Zotero]. The Oxford English Dictionary also cites 1816 as the first instance that “drive” was applied to a carriage road, especially a private road leading to a house.</ref> It offered the carriage traveler varied scenery, [[view]]s of distant [[prospect]]s, and glimpses of the main house [Figs. 2–4]. Views of the house that became evident as one approached from an oblique angle, [[A. J. Downing|Downing]] noted, were beneficial for “displaying not only the beauty of the architectural façade but also one of the end elevations.” Thus, the [[view]]s gave “a more complete idea of the size, character, or elegance of the building.” Where possible, these modern drives took advantage of the natural scenery, as in [[A. J. Downing|Downing]]’s design for [[Montgomery place|Montgomery Place]] on the Hudson, where he followed his own advice that a road “should ''never curve without some reason'', either real or apparent [his italics].” The intricacy of the circulation routes and their incorporation of [[view]]s are further exemplified in John Notman’s plan of 1846 for Woodlawn in Princeton, N.J. [Fig. 5]. | As the term itself implies, a drive was part of the processional experience of the natural or [[picturesque]] landscape. <ref>Much of Stephen Daniels’s discussion of the relation of Humphry Repton’s landscape design to road transportation in England is relevant to American landscape practice in the sec.ond quarter of the nineteenth century, although Repton himself does not appear to have used the term “drive” to refer to a road. See Daniels, “On the Road with Humphry Repton,” ''Journal of Garden History'' 16, no. 3 (autumn 1996): 170–91, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/3GKTB645 view on Zotero]. The Oxford English Dictionary also cites 1816 as the first instance that “drive” was applied to a carriage road, especially a private road leading to a house.</ref> It offered the carriage traveler varied scenery, [[view]]s of distant [[prospect]]s, and glimpses of the main house [Figs. 2–4]. Views of the house that became evident as one approached from an oblique angle, [[A. J. Downing|Downing]] noted, were beneficial for “displaying not only the beauty of the architectural façade but also one of the end elevations.” Thus, the [[view]]s gave “a more complete idea of the size, character, or elegance of the building.” Where possible, these modern drives took advantage of the natural scenery, as in [[A. J. Downing|Downing]]’s design for [[Montgomery place|Montgomery Place]] on the Hudson, where he followed his own advice that a road “should ''never curve without some reason'', either real or apparent [his italics].” The intricacy of the circulation routes and their incorporation of [[view]]s are further exemplified in John Notman’s plan of 1846 for Woodlawn in Princeton, N.J. [Fig. 5]. | ||

| − | The feature of the drive in public space offered a more affordable venue for pedestrians and horseback riders to enjoy the natural and artificially constructed beauty of the Schuylkill River and Fairmount Waterworks, Gray’s Ferry, and Laurel Hill Cemetery in Philadelphia [Fig. 6]. [[A. J. Downing|Downing]]’s plan for Washington, D.C., incorporated several miles of drives for carriages (as opposed to walks for pedestrians) to enable visitors to circulate through the national park. In this case, the drive was also a means to an end, allowing visitors to benefit from the didactic purposes of the “sylvan museum.” | + | The feature of the drive in public space offered a more affordable venue for pedestrians and horseback riders to enjoy the natural and artificially constructed beauty of the [[Schuylkill River]] and Fairmount Waterworks, Gray’s Ferry, and Laurel Hill Cemetery in Philadelphia [Fig. 6]. [[A. J. Downing|Downing]]’s plan for Washington, D.C., incorporated several miles of drives for carriages (as opposed to walks for pedestrians) to enable visitors to circulate through the national park. In this case, the drive was also a means to an end, allowing visitors to benefit from the didactic purposes of the “sylvan museum.” |

The attention given in American landscape designs of the 1840s to circulation routes suitable for carriages in both public and residential space may partly reflect the technological innovations in vehicle suspension systems that had developed in England. These improvements and the simultaneous efforts to develop roadways allowed faster travel that, in turn, was instrumental in the growing practice of touring British country estates. <ref>Daniels, “On the Road with Humphry Repton,” 170–73, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/3GKTB645 view on Zotero].</ref> While touring was not as highly developed in America, landscape designs often incorporated the same aesthetic principles of opening [[view]]s and creating a varied experience for the visitor driving through the landscape. <ref>For an overview of the history of carriage design in America, see Merri McIntyre Ferrell, “A Harmony of Parts: The Aesthetics of Carriages in Nineteenth-Century America,” in | The attention given in American landscape designs of the 1840s to circulation routes suitable for carriages in both public and residential space may partly reflect the technological innovations in vehicle suspension systems that had developed in England. These improvements and the simultaneous efforts to develop roadways allowed faster travel that, in turn, was instrumental in the growing practice of touring British country estates. <ref>Daniels, “On the Road with Humphry Repton,” 170–73, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/3GKTB645 view on Zotero].</ref> While touring was not as highly developed in America, landscape designs often incorporated the same aesthetic principles of opening [[view]]s and creating a varied experience for the visitor driving through the landscape. <ref>For an overview of the history of carriage design in America, see Merri McIntyre Ferrell, “A Harmony of Parts: The Aesthetics of Carriages in Nineteenth-Century America,” in | ||

Revision as of 14:59, June 6, 2017

See also: Avenue

History

Approaches, roads, avenues, and other circulation routes have always been an important component of American landscape design, but the term drive as a designation for a carriage road (as opposed to walks and paths for pedestrians and horseback riders) did not come into common usage in America until the second quarter of the nineteenth century. Even then it appears to have been used only by treatise writers. Although earlier sites, such as Monticello and Mount Vernon, included similar serpentine ways leading to the house, these routes usually were designated as avenues or roads.

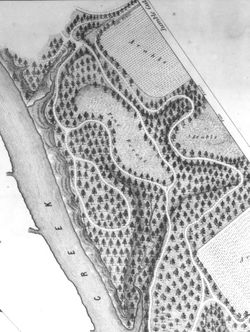

A. J. Downing distinguished a drive from an approach, placing emphasis on the location of the roadways within an estate. In his lexicon, an approach, whether straight in the manner of the “ancient style” or serpentine following the “modern style,” led the traveler from the public road to the house. The drive, in contrast, began where the approach terminated and carried the visitor through the estate, as with the several miles of graveled drives that he praised at Beaverwyck, near Albany, or the circuitous drives of Anthony Bleeker’s 1847 plan for Point Breeze [Fig. 1] in Bordentown, N.J. Other treatise writers, such as James E. Teschemacher in 1835, used the term “drive” more broadly to include curvilinear drives to the house, those that Downing would have called “approaches.” The majority of descriptions of drives, with their sweeping curves (which allowed one to experience the changing scenery of the landscape), relate to the large estates of America’s wealthiest families. Only by the mid-nineteenth century did the term’s meaning shift, when George Jaques in 1852 applied the term to circulation routes at residential dwellings of modest scale. As such, the meaning began to approximate the contemporary term driveway.

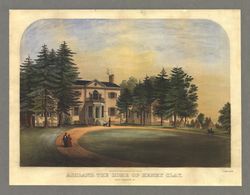

As the term itself implies, a drive was part of the processional experience of the natural or picturesque landscape. [1] It offered the carriage traveler varied scenery, views of distant prospects, and glimpses of the main house [Figs. 2–4]. Views of the house that became evident as one approached from an oblique angle, Downing noted, were beneficial for “displaying not only the beauty of the architectural façade but also one of the end elevations.” Thus, the views gave “a more complete idea of the size, character, or elegance of the building.” Where possible, these modern drives took advantage of the natural scenery, as in Downing’s design for Montgomery Place on the Hudson, where he followed his own advice that a road “should never curve without some reason, either real or apparent [his italics].” The intricacy of the circulation routes and their incorporation of views are further exemplified in John Notman’s plan of 1846 for Woodlawn in Princeton, N.J. [Fig. 5].

The feature of the drive in public space offered a more affordable venue for pedestrians and horseback riders to enjoy the natural and artificially constructed beauty of the Schuylkill River and Fairmount Waterworks, Gray’s Ferry, and Laurel Hill Cemetery in Philadelphia [Fig. 6]. Downing’s plan for Washington, D.C., incorporated several miles of drives for carriages (as opposed to walks for pedestrians) to enable visitors to circulate through the national park. In this case, the drive was also a means to an end, allowing visitors to benefit from the didactic purposes of the “sylvan museum.”

The attention given in American landscape designs of the 1840s to circulation routes suitable for carriages in both public and residential space may partly reflect the technological innovations in vehicle suspension systems that had developed in England. These improvements and the simultaneous efforts to develop roadways allowed faster travel that, in turn, was instrumental in the growing practice of touring British country estates. [2] While touring was not as highly developed in America, landscape designs often incorporated the same aesthetic principles of opening views and creating a varied experience for the visitor driving through the landscape. [3] Downing cautioned that “the curves should never be so great, or lead over surfaces so unequal, as to make it disagreeable to drive upon them.”

-- Elizabeth Kryder-Reid

Texts

Usage

- Downing, A. J., October 1847, describing Montgomery Place, country home of Mrs. Edward (Louise) Livingston, Dutchess County, N.Y. (quoted in Haley 1988: 45) [4]

- “On the south [natural boundary of the estate] is a rich oak wood, in the centre of which is a private drive.”

- Downing, A. J., 1849, describing Montgomery Place, country home of Mrs. Edward (Louise) Livingston, Dutchess County, N.Y. (p. 49) [5]

- “A large conservatory, an exotic garden, an arboretum, etc., are among the features of interest in this admirable residence. Including a drive through a fine bit of natural wood, south of the mansion, there are five miles of highly varied and picturesque private roads and walks, through the pleasure-grounds of Montgomery Place.”

- Downing, A. J., 1849, describing Beaverwyck, the seat of William P. Van Rensselaer, near Albany, N.Y. (p. 51) [5]

- “The whole estate is ten or twelve miles square. . . . The home residence embraces several hundred acres, with a large level lawn, bordered by highly varied surface of hill and dale. . . . The grounds are yet newly laid out, but with much judgement; and six or seven miles of winding gravelled roads and walks have been formed—their boundaries now leading over level meadows, and now winding through woody dells. The drives thus afforded, are almost unrivalled in extent and variety, and give the stranger or guest, an opportunity of seeing the near and distant views to the best advantage.” [Fig. 7]

- Downing, A. J., December, 1851, “State and Prospects of Horticulture” (Horticulturist 6: 540–41) [6]

- “The plan [for a public ground in Washington] embraces four or five miles of carriage-drive—walks for pedestrians—ponds of water, fountains and statues—picturesque groupings of trees and shrubs, and a complete collection of all the trees that belong to North America. It will, if carried out as it has been undertaken, undoubtedly give a great impetus to the popular taste in landscape-gardening and the culture of ornamental trees; and as the climate of Washington is one peculiarly adapted to this purpose—this national park may be made a sylvan museum such as it would be difficult to equal in beauty and variety in any part of the world.” [Fig. 8]

Citations

- Loudon, J. C., 1826, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (p. 1021) [7]

- “7267. The riding, or drive, is a road indicated rather than formed, which passes through the most interesting and distant parts of a residence not seen in detail from the walks, and as far into the adjoining lands of wildness or cultivation, as the property of the owner extends. It is also frequently conducted as much farther as the disposition of adjoining proprietors permits, or the general face of the country renders desirable.”

- Teschemacher, James E., 1 November 1835, “On Horticultural Architecture” (Horticultural Register 1: 411) [8]

- “The approach to the house should be by a broad semi-circular drive intersecting the lawns, and leading by branches to the stables and out buildings, as well as to the flower and kitchen gardens; this last, if near the house, must be completely concealed, either by walls covered with fruit trees, or by shrubberies, and may be preferably laid out in a series of parallelograms.”

- Downing, A. J., 1849, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (pp. 337, 341–42) [5]

- “There are two guiding principles which have been laid down for the formation of Approach roads. The first, that the curves should never be so great, or lead over surfaces so unequal, as to make it disagreeable to drive upon them; and the second, that the road should never curve without some reason, either real or apparent.

- “The Drive is a variety of road rarely seen among us, yet which may be made a very agreeable feature in some of our country residences, at a small expense. It is intended for exercise more secluded than that upon the public road, and to show the interesting portions of the place from the carriage, or on horseback. Of course it can only be formed upon places of considerable extent; but it enhances the enjoyment of such places very highly, in the estimation of those who are fond of equestrian exercises. It generally commences where the approach terminates, viz. near the house: and from thence, proceeds in the same easy curvilinear manner through various parts of the grounds, farm, or estate. Sometimes it sweeps through the pleasure grounds, and returns along the very beach of the river, beneath the fine over-hanging foliage of its projecting bank; sometimes it proceeds towards some favorite point of view, or interesting spot on the landscape; or at others it leaves the lawn and traverses the farm, giving the proprietor an opportunity to examine his crops, or exhibit his agricultural resources to his friends.”

- Jaques, George, January 1852, “Landscape Gardening in New-England” (Horticulturist 7: 35) [9]

- “A gracefully curved drive or walk, (from the public street to the buildings,) entering through an irregular group of trees, and forced into its curvature by another little group, will of itself impart to a rural home charms far more pleasing than ten times their cost could infuse into the stiff, old straight-lined primness of the ancient style.”

Images

Inscribed

J. C. Loudon, Plan of a ferme ornée with wild and irregular hedges, in An encyclopædia of gardening, (1826), p. 1023, fig. 722.

Associated

Anonymous, "Beaverwyck, the Seat of Wm. P. Van Rensselaer, Esq.," in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, (1849), pl. opp. p. 51, fig. 7.

A. J. Downing, "Plan showing proposed method of laying out the public grounds at Washington," 1851.

A. J. Downing, Plan Showing Proposed Method of Laying Out the Public Grounds at Washington, 1851. Manuscript copy by Nathaniel Michler, 1867.

Attributed

Anne-Marguerite-Henriette Rouillé de Marigny Hyde de Neuville, Washington City, 1821.

Anonymous, "Kenwood, Residence of J. Rathbone, Esq. near Albany, N.Y.," in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, (1849), pl. opp. p. 50, fig. 9.

Anonymous, "Villa of Theodore Lyman, Esq., near Boston," in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, (1849), p. 387, fig. 48.

Notes

- ↑ Much of Stephen Daniels’s discussion of the relation of Humphry Repton’s landscape design to road transportation in England is relevant to American landscape practice in the sec.ond quarter of the nineteenth century, although Repton himself does not appear to have used the term “drive” to refer to a road. See Daniels, “On the Road with Humphry Repton,” Journal of Garden History 16, no. 3 (autumn 1996): 170–91, view on Zotero. The Oxford English Dictionary also cites 1816 as the first instance that “drive” was applied to a carriage road, especially a private road leading to a house.

- ↑ Daniels, “On the Road with Humphry Repton,” 170–73, view on Zotero.

- ↑ For an overview of the history of carriage design in America, see Merri McIntyre Ferrell, “A Harmony of Parts: The Aesthetics of Carriages in Nineteenth-Century America,” in Nineteenth Century American Carriages: Their Manufacture, Deco.ration and Use (Stony Brook, N.Y.: The Museums at Stony Brook, 1987), 34–65, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Jacquetta M. Haley, ed., Pleasure Grounds: Andrew Jackson Downing and Montgomery Place (Tarrytown, N.Y.: Sleepy Hollow Press, 1988), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 A. J. [Andrew Jackson] Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America, 4th edn (Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1991), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Andrew Jackson Downing, "The State and Prospects of Horticulture", The Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste, 6 (1851), 537–41, view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening, 4th edn (London: Longman et al, 1826), view on Zotero.

- ↑ James E. Teschemacher, "On Horticultural Architecture", The Horticultural Register and Gardener’s Magazine, 1 (1835), 157–61, view on Zotero.

- ↑ George Jaques, "Landscape Gardening in New-England", The Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste, 7 (1852), 33–36, view on Zotero.