Frances Palmer

Frances (“Fanny”) Flora Bond Palmer (June 26, 1812–August 20, 1876) was one of the few women to work as a professional lithographer in the mid-nineteenth century United States. She created prints in the 1840s that illustrated several important botanical and architectural texts, including William H. Ranlett’s The Architect (1847). Palmer joined Nathaniel Currier’s lithography firm full-time around 1849 and became one of the company’s most prolific artists.

History

The artist and lithographer Frances Palmer [Fig. 1] emigrated from her birthplace of Leister, England, to the United States in 1843 with her husband, Edmund Seymour Palmer (1809–1859), their children, and her younger siblings Maria Bond (b. 1815) and Robert Bond Jr. (b. 1821). She became well known as a professional lithographer during the 1840s–1860s while working in New York City. In the early part of her career in New York, Palmer designed and printed illustrations for several important botanical and architectural texts. Sometime around 1849 she joined the staff as a full-time artist at the N. Currier lithography firm (later known as Currier & Ives).

Palmer began her career in Leister, England. Her first artistic training likely occurred at Miss Linwood’s academy for girls, a school Palmer attended as a child that was run by the “nationally recognized artist” Mary Linwood (1755–1845). Soon after marrying Edmund Palmer in 1832, the twenty-year-old Frances Palmer began to work as a professional artist.[1] By 1841 Palmer and her husband had opened a lithography business together in Leister, for which Frances worked primarily as the artist and draftsman and Edmund as the printer. They advertised experience printing a wide range of subjects, including “Views, architectural and botanical drawings, maps, plans of estates, railway sections, elevations, law forms, invoice heads, tickets, checks, fac similes [sic], circulars and writings, of every description, and in every character.”[2] The Palmers received a commission to produce illustrations of picturesque local views for a publication by the local scholar Thomas Rossell Potter entitled The History and Antiquities of Charnwood Forest (1842).[3] They also published Sketches in Leicestershire (1842–43), a portfolio of twenty-seven local views, thirteen of which were fully designed and lithographed by Frances (view text – July 1, 1842, review).[4]

Soon after arriving in New York City in 1843 the Palmers partnered with the established lithographer Edward Jones, but by 1846 they had started their own firm under the name “F. & S. Palmer.” During this period, Frances Palmer also began to show her watercolor landscapes at exhibitions in New York City, including the 1844 annual exhibition at the National Academy of Design.[5] According to the scholar Charlotte Streifer Rubinstein, Palmer experimented with an even wider variety of subjects in New York than she had in England: “Whereas in England Palmer had restricted herself largely to picturesque local and historic sites, she now drew ships, battle scenes, botanicals, landscapes, architecture, sheet-music covers, cartoons, and magazine illustrations.”[6]

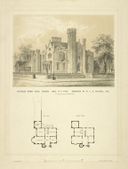

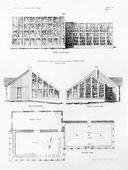

Palmer’s architectural prints from this period include an 1844 lithographic depiction of a fashionable gothic villa designed by architect A. J. Davis that stood on 5th Avenue in New York City [Fig. 2]. Davis’s original sepia, ink, and watercolor drawing served as the basis for Palmer’s print, but she added additional figures strolling by the mansion to integrate the architecture into its environment. In 1847 the Palmers also created the illustrations for William H. Ranlett’s two-volume The Architect based on Ranlett’s drawings [Fig. 3]. Through this project, Frances Palmer became well acquainted with a variety of Victorian architectural styles that she later integrated into her own compositions when creating suburban scenes for Currier & Ives.[7] Ranlett praised Frances Palmer’s work in the “Advertisement” at the front of the first volume of The Architect, noting that the “most difficult” of the illustrations were “executed on the stones by Mrs. F. Palmer, who stands at the head of the art” (view text).

In 1847 the Palmers also published some of Frances’s original landscape views in The New York Drawing Book, a series of two four-page booklets that featured original compositions for art students to copy. Two of the lithographs feature scenes from Brooklyn’s Greenwood Cemetery. Old Entrance to Greenwood Cemetery [Fig. 4] depicts a road curving past a gateway and fence into a wooded landscape with a view of boats on the Gowanus Bay visible in the background. Sylvan Lake, Greenwood Cemetery shows a woman and young child taking in a picturesque view of one of the cemetery’s placid, tree-lined lakes [Fig. 5].

The Palmers lithographed many of the illustrations for Asa B. Strong’s American Flora, or History of Plants and Wildflowers (1848), a popular four-volume encyclopedia that advertised itself on the title page as “a book of reference for botanists, physicians, florists, gardeners, students, etc.”[8] Frances Palmer’s lithographs include the frontispiece for the second volume [Fig. 6], sixteen lithographs of Strong’s original botanical drawings that appear in the second and third volumes, including the Caper Bush [Fig. 7], and a portrait of the Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778) that appears in the third volume.[9]

Palmer soon began to publish prints under her own name—no longer “F. & S. Palmer”—and at a new address, indicating that the professional partnership with her husband had come to an end, likely due, at least in part, to financial challenges. By 1849, the well-known New York City lithographer Nathaniel Currier (1813–1888) began to use Palmer’s work regularly as the basis for prints published by his firm, although initially he did not include her name below the images. However, by the end of the year, he printed Palmer’s name (“F. F. Palmer”) on two prints, View of New York. From Brooklyn Heights and View of New York. From Weehawken—North River [Fig. 8], a rare recognition for the period as most artists working for Currier remained anonymous. With her new full-time position at the N. Currier lithography firm (renamed Currier & Ives in 1857), Palmer became the primary earner for her family.[10] In her early days with N. Currier, Palmer sometimes traveled out to Long Island in Currier’s carriage to sketch with pencil background material—farmhouses and barns, fences, etc.—to serve as source material for the firm’s large staff.[11] While working for N. Currier, she produced approximately two hundred prints depicting a wide variety of subjects, including city and suburban views, marine subjects, farm scenes, suburban and country homes, western landscapes, and still lifes, among others. She also took on freelance work with the assistance of male apprentices that she trained and paid to assist her (view text – Penny 1863). Palmer worked for Currier & Ives until 1868 and remained in the United States until her death from tuberculosis in 1876.[12]

—Lacey Baradel

Texts

- Review of Frances Palmer’s and Edmund Palmer’s lithographs, May 13, 1842, published in the Leicester Journal (quoted in Rubinstein 2018: 16)

- “Leicester General News Room and Library—A perspective view of this ornament to our town, drawn on stone, by Mrs. Palmer, executed in tinted Lithography, by Mr. E. J. [sic] Palmer, has just been published. . . . In this specimen before us, we have proof also that the difficult process of Lithography is skilfully [sic] conducted by a resident Lithographer. Of this view, although we pretend not that Mrs. Palmer’s drawing on stone equals in the handling the productions of the long-practiced Barnard, nor that the finer specimens of [Charles Joseph] Hulmandel’s [sic] Press do not surpass, in the more delicate effects, those of Mr. Palmer’s; it is impossible to deny that the former is an accomplished Artist, and the latter a skilful [sic] director in this beautiful art; and we look forward with pleasure to the promised appearance of their joint efforts in the publication of a series of views, in numbers, of the most picturesque localities in our Town and Country.”

- Review of Frances Palmer’s and Edmund Palmer’s lithographs, July 1, 1842, published in the Leicester Journal (quoted in Rubinstein 2018: 16)

- “SKETCHES IN LEICESTERSHIRE—We take the earliest opportunity of recommending this very promising work, the first number of which has just appeared to the notice of our readers. The views. . . The Hanging Rock; St. Mary’s Church, Leicester, from the S.W.; and that most picturesque and interesting of all the heights included in this extensive range of the Charnwood, Beacon Hill. Each is managed with great artistic effect; and the manner in which the lithographer has fulfilled his [sic] task is deserving of every commendation. . . . The view of Beacon Hill is in Mrs. Palmer’s most tasteful and successful style, and is distinguished by a boldness and freedom not often exhibited by a female pencil. . . . The tint delicately thrown upon the sky moreover, (apparently a soft and tranquil autumnal heaven,) is the very finish required as a contrast to the stern features of the rugged landscape which frowns beneath it. . . . We cordially recommend Mrs. Palmer’s work to the notice, not only of all attached to our local scenery, but of all interested (as who in these days is not!) in the general progress and advancement of the graphic art.” back up to History

- William H. Ranlett, describing Frances Palmer’s work (Ranlett 1847 1:1)[13]

- “The volume contains 60 plates—19 of them tinted in a style of lithography which will commend itself to every judge of art. The most difficult of them being executed on the stones by Mrs. F. PALMER, who stands at the head of the art. . . . The plates are from the well-known lithographic press-room of Messrs. PALMER.” back up to History

- Virginia Penny, describing Frances Palmer’s career and working process (Penny 1863: 69)[14]

- “Mrs. P., Brooklyn, an English lady, learned to draw when eight years old, and studied lithography with a distinguished artist of London, who executed entirely with his left hand, having lost three fingers on his right when he was a child. She has spent twenty-two years in lithographing—seventeen of them in this county. She is probably the only lady professionally engaged in this business in the United States. She has earned almost constantly, I was told, from $12 to $30 a week. . . . Mrs. P. excels in architectural drawing. She thinks one must have the talent of an artist, and great practice with the pencil, to succeed. She has given instruction to several youths, but never to one of her own sex. One must be articled, and pass through a regular course of advancement, to follow it advantageously. To an apprentice, after two or three years’ practice, a small premium is paid. She had one youth to learn of her, who, after four years’ time, received $7 a week from her for his work. She thinks there will be employment to a few well qualified. She has always kept busy.” back up to History

Images

E. Jones, F. [Fanny] Palmer, and E. Palmer (lithographers), Alexander Jackson Davis (architect), Suburban Gothic Villa, Murray Hill, N.Y. City. Residence of W. C. Waddell, Esq. 5th Avenue, Between 37 & 38th Street. Below, Plans of First and Second Floors, n.d.

Other Resources

Library of Congress Authority File

“Lasting Impressions: The Artists of Currier & Ives,” Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library

Notes

- ↑ Linwood specialized in creating needlework copies of paintings by artists such as Thomas Gainsborough, Sir Joshua Reynolds, and Rembrandt van Rijn and framing them under glass to emulate the original oil paintings. Charlotte Streifer Rubinstein, Fanny Palmer: The Life and Work of a Currier & Ives Artist, ed. Diann Benti (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 2018), 2, 6, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Palmer, Frances, The Grove Encyclopedia of American, vol. 4, edited by Joan M. Marter (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 10. Quote from advertisement in Thomas Cook’s Trade Directory of Leister (1842); qtd. in Rubinstein 2018, 12.

- ↑ T. R. Potter, The History and Antiquities of Charnwood Forest (London: Hamilton, Adams, and Co., 1842), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Rubinstein 2018, 16.

- ↑ Rubinstein 2018, 23–24 view on Zotero. See also Mary Bartlett Cowdrey, "Fanny Palmer, an American Lithographer," in Prints: Thirteen Illustrated Essays on the Art of the Print, ed. Carl Zigrosser (New York: Holt, Reinhart, and Winston, 1962), 217–34, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Rubinstein 2018, 27.

- ↑ Rubinstein 2018, 30–31, 46 view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. B. Strong, The American Flora, or History of Plants and Wild Flowers (New York: Green & Strong, 1848), view on Zotero. Other lithographs were completed by several different lithographers, including W. M. Moody, E. Whitefield, and F. Michelin. See Rubinstein 2018, 272 view on Zotero.

- ↑ For a full list of the lithographs in Strong’s encyclopedia that were executed by the Palmers, see Rubinstein 2018, 272–74 view on Zotero.

- ↑ By the 1850 federal census, Seymour Palmer’s occupation was listed as a tavern keeper and he seems to have abandoned work in the printing trade from this point on. By 1855 Edmund Palmer no longer appeared in the city’s business directories and was described by at least one contemporary acquaintance as “a ne’er-do-well.” Rubinstein 2018, 46, 50, 52, 55 view on Zotero.

- ↑ Rubinstein 2018, 90.

- ↑ According to Rubinstein, no prints by Palmer produced after 1868 have been located and confirmed. Rubinstein 1868, 174 view on Zotero. For a list of prints by (or attributed to) Palmer published by Currier & Ives, see Appendix 3 and 3A in Rubinstein 2018, 281–338.

- ↑ William H. Ranlett, The Architect: A Series of Original Designs, for Domestic and Ornametnal Cottages and Villas, Connected with Landscape Gardening, Adapted to the United States… (New York: Dewitt & Davenport, 1847), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Virginia Penny, The Employments of Women: A Cyclopaedia of Woman’s Work (Boston: Walker, Wise, & Company, 1863), view on Zotero.