Difference between revisions of "Springside"

V-federici (talk | contribs) m (→Notes) |

V-federici (talk | contribs) m (→Notes) |

||

| Line 45: | Line 45: | ||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| − | </ | + | <references/> |

<hr> | <hr> | ||

Revision as of 20:01, August 18, 2021

Springside, the estate of Matthew Vassar in Poughkeepsie, New York, was designed by nurseryman, landscape designer, and author, Andrew Jackson Downing (1815-1852) at the apex of his career. It represents the most complete expression of his theory and practice. A. J. Downing was engaged in 1850 by Matthew Vassar (1792-1868), a wealthy beer brewer, philanthropist, and founder of Vassar College. Springside is one of the few projects by the partnership of Downing & Calvert Vaux (1825—1895) that has been preserved significantly intact.

Overview

Alternate Names: Springside Site Dates: 1850 to present Site Owner(s): Matthew Vassar (1850-1868), John O. Whitehouse (1868-), Eugene N. Howells (through 1901), William Nelson (1901-), Gerald Nelson, Geraldine Nelson Acker, and Gertrude Nelson Fitzpatrick (through 1972), Robert S. Ackerman (circa 1971—), Springside Landscape Restoration (1990 – present) Associated People: Caleb N. Bement (manager, superintendent), Mrs. Bement. Location: Poughkeepsie, NY Condition: extant; altered Google coordinates: 41.6902924,-73.931952

History

Around 1850, the agricultural landscape of the future site of Springside attracted the interest of the Board of Trustees of Poughkeepsie who hoped to establish a rural cemetery. Matthew Vassar, already a prominent figure in the city and president of the Board, purchased the farmland called “Allan farm” to secure the location.[1] A successful businessman and founder of Vassar College, he was on the board of three different banks, president of several societies in the region, including the Hudson River Railroad and the Lyceum of Literature and Mechanical Arts and president of the Board of Trustees of the city of Poughkeepsie in 1835.[2]

Following a cholera epidemic in 1842, the need for a larger burial ground became a pressing necessity for Poughkeepsie.[3] At the time, the development of rural cemeteries was seen, according to Downing scholar Robert M. Toole, “as a reaction to the unhealthy, unattracted, and overcrowded conditions of older church yard burial plots inherited from the Colonial period.”[4] Following the model of the Mount Auburn Cemetery outside of Boston, new burial grounds were built with particular attention to the design qualities of the landscape. Downing had written about the benefits of the rural cemetery in his periodical The Horticulturist in 1849, the year before he received the commission for Springside.[5] [view text]

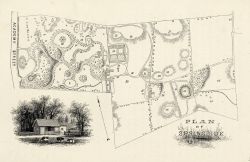

The site was initially considered for its location—Academy Street on the west, a wooded backdrop on the south, and surrounding grounds cleared by agriculture throughout—which contributed to its qualities as an enclosed, separate place, or as described, “a paradise,” at the same time functional and pleasing.[6] Vassar historian Benson J. Lossing recalled that while the village was still deciding whether to use the site, Vassar had begun “improvements of the property in a manner suitable for a cemetery or the pleasure-grounds of a private residence.”[7] [Fig. 1]

Vassar renamed the property Springside “because of the numerous fountains that were bubbling up here and there.”[8] When the city moved away from the idea of using this location, the property became Vassar’s own residence on which he eventually spent over $100,000, turning a farm that he had purchased for $8,000 into a celebrated estate.[9] [view text]

The plan of Springside was then in the hands of the most prominent American landscape architect of the time, A. J. Downing, who, through his popular publications, promoted a natural style for American domestic landscape design. With his partner Calvert Vaux, (1825-1895) he would design Vassar’s residence in the Gothic Revival or Hudson River Bracketed style of architecture known for its “asymmetric outline, sloping gables, irregular windows and rustic finish that existed in "harmonious combination" with a more natural, unregulated landscape.”[10] Through these features, Springside embodied Downing's principles of “variety, unity and harmony” in both architecture and landscape design.[11] This combination of natural and designed features was recalled by Calvert Vaux in 1857, while revisiting Springside. [view text]

In his biography “Vassar College and its Founder,” Lossing dedicated a lengthy description to Springside adding a plan of the park along with illustrations of notable features—such as Willow Spring and Poplar Summit. [view text]

He wrote that Springside featured an entrance with a “broad, gravely road,” as well as a deer-park, a rustic bridge, a duck-pond, a smaller pond with gold fishes, a rustic cabin roofed with pantiles, a gardener’s cottage as well as evergreen trees, meadows, shrubs, hemlock saplings, “groups of stones, among which [were] rustic seats,” a conservatory with a crystal roof, as well as a pagoda and a summer-house.[12][Fig. 2]

According to Lossing, at the time of writing in 1867, Springside was characterized by a picturesque landscape design that emphasized “the raw materials of wood, water, and surface” for a charming effect, therefore confirming Downing’s departure from the geometric style of the 18th and early 19th century.[13] Other scholars, such as Toole, see Springside as an exemplar of Downing’s Beautiful style rather than the picturesque. [view text]

Toole also argued that Vassar himself became invested in the design of the grounds as demonstrated by the literature on the subject in his library.[14] He often discussed the making of Springside with colleagues, friends, and family.[15] Whether rural cemetery or country private estate, Springside was the result of the intrinsic landscape features that attracted Downing, such as the variety of its terrain and vegetation, coupled with Vassar’s own vision for the development of his property.[16] Harvey K. Flad highlights how Springside was an ideal ground for Downing’s approach to landscape design with its balanced combination between a “park-like” and a “pastoral landscape” that could embed both “sylvan and pastoral beauty.”[17] Importantly, Downing added “utility” to a picturesque landscape that was as much as a pleasure ground as a “working farm with kitchen garden, stables, orchard, and pasture,”[18] in the tradition of the ferme ornée or ornamental farm. [Fig. 3]

In Spring 1852, the local paper The Poughkeepsie Eagle, published an “Ode to Springside,” [view text] and reported that Vassar “was beautifying the place with ornamental trees, walks, ponds, fountains etc.,” and “more than 1000 forest trees,” while the previous year “he set out a very large number of evergreen trees along the winding paths.”[19] Vassar commissioned several paintings from English landscape painter Henry Gritten that record the landscape’s features and the improvements under his stewardship. [Fig. 4] The paintings, executed in 1852, are important documents of how Downing probably last saw Springside.[20]

Many of Vassar’s contemporaries, including poets and musicians, have celebrated Springside or taken inspiration from it as the site became known. During Vassar’s lifetime he himself opened the park to visitors regularly. In 1852, Russell Comstock, a visitor of Springside, described the “pictorial” quality of the location, emphasizing the rhythm of hills, meadows and watercourses. [view text]

Vassar used Springside as a summer residence until he permanently moved there in 1864. He and his wife Catherine Valentine, lived in the caretaker’s cottage while waiting for a large villa to be built. Both were designed by Downing in 1851 and then Vaux in 1854, but were never executed.[21] After Vassar’s death, Springside remained a one-family residence through the early 1970s when it was purchased in part by Robert S. Ackerman, a developer. A request for re-zoning in 1968 alerted local preservationists who petitioned to rescue the site from the peril of commercial use. Although Springside was granted the status of National Historic Landmark in August 1969, a combination of neglect and fire destroyed all but one of the original twelve buildings. Only the Gatehouse remains. During these years, the unregulated growth of the vegetation compromised much of Downing’s original landscape plan.[22] Small improvements were made under various owners and some of the land sold. The rest was neglected, allowing Springside to remain almost intact since Vassar’s death.[23]

Today, the park is managed by volunteers of the Springside Landscape Restoration, an association that took title of the site in the 1990. The park is a National Historic Landmark comprised of 23.6 of the original 43 acres of land.

Texts

Notes

- ↑ Lossing, Benson John, Vassar College and its founder, New York, 1867, pp. 59-60, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Flad, K. Harvey “Matthew Vassar’s Springside:... the hand of Art when guided by Taste,” in Prophet with Honor, Dumbarton Oaks, 1989, p. 220, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Toth, Kyle, Bringing the Public Back to the Park: Analysis of Springside Landscape’s Preservation Maintenance Plan (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA (2018), p. 15, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Toole, M. Robert, “Springside: A. J. Downing's only extant garden,” in The Journal of Garden History, 9:1, 20-39, p. 20, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Downing, Andrew Jackson, “Public Cemeteries and Public Gardens,” in Landscape Gardening and Rural Architecture, New York and London, 1861, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Toole, p. 20 and 30 and footnotes.

- ↑ Lossing, p. 61

- ↑ Lossing, p. 61.

- ↑ Source - Springside Historic Site, http://springsidelandmark.org/history/, accessed July 27, 2021.

- ↑ Rodrigues, Sarah, 2004, Springside, in Vassar Encyclopedia, [1], accessed July 27, 2021.

- ↑ Rodrigues, Sarah, 2004, Springside, in Vassar Encyclopedia, http://vcencyclopedia.vassar.edu/matthew-vassar/springside.html, accessed July 27, 2021.

- ↑ Lossing, pp 65-69, 75-76, 79.

- ↑ Downing, Andrew Jackson, 1844, Excerpt from A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America;... (1844: 59—60), vie on Zotero.

- ↑ Toole, p. 21.

- ↑ See Flad and Vassar’s correspondence with his biographer Lossing as well as records in his nephew’s diary entries as mentioned in Flad, K. Harvey, “Matthew Vassar’s Springside:... the hand of Art when guided by Taste,” pp 223 and footnotes, and 245-246 and footnotes.

- ↑ Flad, pp. 223-224, see also Toole, p. 22.

- ↑ Quotes by Downing’s “Management of Large Places” in Flad, K. Harvey, “Matthew Vassar’s Springside:... the hand of Art when guided by Taste,” p. 242, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Flad, p. 243

- ↑ Quote in Flad, p. 243

- ↑ Toole, p. 25

- ↑ Toole, p. 25

- ↑ Source - http://springsidelandmark.org/history/, accessed July 27, 2021.

- ↑ Source - http://springsidelandmark.org/history/, accessed July 27, 2021.