Difference between revisions of "Bunker Hill Monument"

M-westerby (talk | contribs) |

M-westerby (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

|Associated people={{Associated person | |Associated people={{Associated person | ||

|Name=Robert Mills | |Name=Robert Mills | ||

| + | |Role=Design Competitor | ||

|From Present=No | |From Present=No | ||

|From Date=1781 | |From Date=1781 | ||

| Line 44: | Line 45: | ||

}}{{Associated person | }}{{Associated person | ||

|Name=Horatio Greenough | |Name=Horatio Greenough | ||

| + | |Role=Design Competitor | ||

|From Present=No | |From Present=No | ||

|From Date=1805 | |From Date=1805 | ||

| Line 64: | Line 66: | ||

}}{{Associated person | }}{{Associated person | ||

|Name=Solomon Willard | |Name=Solomon Willard | ||

| + | |Role=Design Winner | ||

|From Present=No | |From Present=No | ||

|From Date=1783 | |From Date=1783 | ||

Revision as of 21:41, August 16, 2021

Overview

Site Dates: 1826–1842

Associated People: Robert Mills 1781–1855, design competitor; Horatio Greenough 1805–1852, design competitor; Solomon Willard 1783–1861, design winner;

Location: Charlestown, MA · 42° 22' 34.86" N, 71° 3' 46.69" W

Condition: Extant

The Bunker Hill Monument in Charlestown, Massachusetts, commemorates a pivotal early battle in the American war for independence. It is the first colossal obelisk erected in the United States.[1]

History

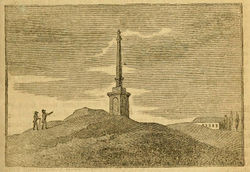

The Battle of Bunker Hill took place on June 17, 1775, on and around Breed’s Hill during the Siege of Boston. Nineteen years later, an 18-foot Tuscan pillar surmounted by a gilt urn was erected in memory of Dr. Joseph Warren (1741–1775), a hero of the battle, by the members of his Masonic Lodge [Fig. 2]. Bunker Hill became a pilgrimage site for patriotic tourism early in the 19th century. Public perception of its importance increased as a result of the well-publicized visit, in 1817, of the newly elected president James Monroe—a symbolic act of national healing following the divisive War of 1812.[2]

In 1823 a group of prominent Massachusetts citizens formed the Bunker Hill Monument Association for the purpose of creating a more ambitious memorial commensurate with the battle’s national importance. The Association envisioned “a simple, majestic, lofty, and permanent monument, which shall carry down to remote ages a testimony . . . to the heroic virtue and courage of those men who began and achieved the independence of their country.”[3] In order to protect the battlefield from encroaching development as the local population grew, the Association’s standing committee purchased 15 acres on the slope of Breed’s Hill and authorized Solomon Willard, a stone worker and builder, to draw the plan for a 221-foot column.

The committee subsequently changed course, opening a design competition in 1825 which attracted 50 entries. Although a column had been specified, a variety of alternative forms were submitted. Robert Mills, an architect who had previously designed the Washington Monument in Baltimore, submitted plans for a column as well as an obelisk, expressing his preference for the latter due to its “lofty character, great strength, and . . . fine surface for inscriptions.”[4] Mills specified that along with inscriptions, the monument was to be ornamented with numerous decorative devices—shields, stars, spears, and wreaths—which could be viewed from a series of platforms around the base and shaft of the obelisk. Horatio Greenough (1805–1852), a student at Harvard University who went on to become a noted sculptor, also submitted a design for an obelisk but in a far simpler form. In his memoirs, published in 1852, Greenough observed: “The obelisk has to my eye a singular aptitude, in its form and character, to call attention to a spot memorable in history. It says but one word, but it speaks loud. If I understand its voice, it says, Here! It says no more.”[5]

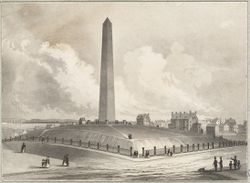

Following extensive debate over the architectural form best suited to communicate the heroic, memorial, and patriotic themes of the monument, the committee determined that the obelisk was “most congenial to republican institutions.”[6] Willard received the commission to construct the monument, which he originally designed with an Egyptian Revival base. Lack of funds required simplification of Willard’s design and the selling of most of the land purchased by the Association [Fig. 1]. Only the summit of the hill was preserved for the monument grounds.[7] Landscape improvements carried out between 1842 and 1847 included grading, planting trees and hedges, laying sidewalks, and installing iron fences [Fig. 3].[8]

The erection of the monument enhanced Bunker Hill’s popularity as a patriotic destination. As tourism increased over the course of the 19th century, it featured frequently in travel literature and the pictorial press, both as a subject in itself and as an immediately recognizable landmark in panoramic views of Boston [Fig. 4]. From the time of the monument’s official dedication in 1843, it also became a favorite site of civic ceremonies and firework displays on the anniversary of the Battle of Bunker Hill and other patriotic occasions.

—Robyn Asleson

Texts

- Standing Committee of the Bunker Hill Monument Association, September 24, 1824, circular about Bunker Hill Monument (quoted in Wheildon 1865: 64–67)[9]

- “The spot itself on which this memorable action took place, is extremely favorable for becoming the site of a monumental structure. . . . An elevated monument on this spot would be the first landmark of the mariner in his approach to our harbor; while the whole neighboring country, . . . with their rich fields, villages and spires; the buildings of the University, the bridges, the numerous ornamental country seats and improved plantations, the whole bounded by a distant line of hills and farming landscape which cannot be surpassed in variety and beauty, would be spread out as in a picture, to the eye of the spectator on the summit of the proposed structure. . . .

- “In forming an estimate of the cost of the structure proposed, a single eye has been had to the principle which dictates its erection. Everything separated from the idea of substantial strength and severe taste has been discarded, as foreign from the grave and serious character both of the men and events to be commemorated. With this principle in view, it has been ascertained that a monumental column, of a classic model, with an elevation to make it the most lofty in the world, may be erected of our fine Chelmsford granite, for about thirty-seven thousand dollars. . . .

- “The beautiful and noble arts of design and architecture have hitherto been engaged in arbitrary and despotic service. The Pyramids and Obelisks of Egypt ; the monumental columns of Trajan and Aurelius, have paid no tribute to the rights and feelings of man. Majestic and graceful as they are, they have no record but that of sovereignty, sometimes cruel and tyrannical, and sometimes mild: but never that of a great, enlightened and generous people. . . . Our fellow-citizens of Baltimore have set us a noble example of redeeming the arts to the cause of free institutions, in the imposing monument they have erected to the memory of those who fell in defending their city. If we cannot be the first to set up a structure of this character, let us not be other than the first to improve upon the example; to arrest and fix the feelings of our generation on the important events of an earlier and more momentous struggle, and to redeem the pledge of gratitude to the high-souled heroes of that trying day.”

- Mills, Robert, March 20, 1825, in a letter to the Bunker Hill Monument Commission (quoted in Gallagher 1935: 204–6)[10]

- “I have the honor to submit for your consideration and approval, a design for the Monument you propose erecting on the spot, where the Brave General Warren and his worthy associates fell; to commemorate their valor, and the gratitude of their Country. . . .

- “In the design for the Monument which I now have the honor to lay before you, I would recommend the adoption of the obelisk form, in preference to the Column—the detail I have affixed to this species of pillar, will be found to give it a peculiarly interesting character, embracing originality of effect with simplicity of design, economy in execution, great solidity and capacity for decoration, reaching to the highest degree of splendor consistant with good taste. . . .

- “The obelisk form is, for monuments, of greater antiquity than the Column as appears from history, being used as early as the days of Ramises King of Egypt in the time of the Trojan War—Kercher reckons up 14 obelisk that were celebrated above the rest, namely, that of Alexandria; that of the Barberins; those of Constantinople; of the Mons Esquilinus; of the Campus Flaminius; of Florence; of Heliopolis; of Ludorisco; of St. Makut, of the Medici of the vatican; of M. Coelius, and that of Pamphila. The highest on record mentioned, is that erected by Ptolemy Philadelphus in memory of Arsinoe.

- “The obelisk form is peculiarly adapted to commemorate great transactions from its lofty character, great strength, and furnishing a fine surface for inscriptions—There is a degree of lightness and beauty in it that affords a finer relief to the eye than can be obtained in the regular proportioned Column.

- “Our monument includes a square of 24 feet at the base above the zocle or plinth, and is 15 feet square at the top—Its total elevation is 220 feet above the pavement—The shaft is divided into four great compartments for inscriptive, and other decorations, which come more immediately under the eye by means of oversailing platforms, enclosed by balastrades, supported as it were by winged globes (symbols of immortality peculiarly of a monumental Character).

- “A series of shields band round the foot of the shaft, representing the 13 States, which form’d the Federal union, as principal, having their arms sculptured on their face—A star, on a plain tablet in connection with the former, represents each the other states which now constitute our Union—the whole surmounted by spears and wreathes.

- “A flight of stone steps, or a rising platform, surround the base, from whence the lower inscriptions are read—

- “This is inclosed by a rich bronzed palisade—The entrance into the monument is from this platform, when a flight of stone steps, winding round a pillar, ascends to the top, and communicates with the several platforms. Between the galleries, on each face of the pillar, a wreath, hung on a speer, encircles the letter W, which is otherwise decorated and constitute apertures for lighting the interior of the Monument—over the Last wreath, and near the apex of the obelisk, a great star is placed, emblematic of the glory to which the name of Warren has risen—A tripod crowns the whole and forms the surmounting of the Monument—This tripod is the classic emblem of immortality.”

- Willard, Solomon, 1825, in a letter to George Ticknor, member of the Bunker Hill Monument Association Standing Committee (quoted in Wheildon 1865: 79)[9]

- “I have made another slight sketch of the obelisk you suggested. I have supposed that the monument would be enclosed by an iron fence and have sketched the frustums of pyramids, in the Egyptian style, at the angles, which may serve as accompaniments and also for a lodge, watch house, &c. The obelisk and base is as sketched before, with the addition of a broad platform and a subterranean entrance.

- “It has always seemed to me that any of the three figures which have been proposed, if well designed, would make a respectable monument. The obelisk I have always preferred for its severe cast and its nearer approach to the simplicity of nature than the others. The column might be more splendid. The character of the obelisk, without a pedestal, seems to me to be strictly appropriate for the occasion and I think would rank first as a specimen of art and be highly creditable to the taste of the age.”

- Mills, Robert, July 1, 1832, in a letter to Richard Walleck (quoted in Gallagher 1935: 102)[10]

- “When the Bunker Hill Monument Committee advertised for designs for the Monument, I took a good deal of pains to study one which should do honor to the memory of those worthies it was intended to commemorate, and prove an ornament to the city it was to overlook. I went into some detail on the subject of monuments generally and in sending them two designs, recommended in strong terms the adoption of the Obelisk design, not only from its combining simplicity and economy with grandeur, but as there was already a column of massy proportions erected in Baltimore, we ought not, therefore, to repeat this figure, but construct one of equally imposing figure.”

- Greenough, Horatio, c. 1851, “The Washington Monument” (quoted in Tuckerman 1853: 82)[11]

- “The obelisk has to my eye a singular aptitude, in its form and character, to call attention to a spot memorable in history. It says but one word, but it speaks loud. If I understand its voice, it says, Here! It says no more. For this reason it was that I designed an obelisk for Bunker Hill, and urged arguments that appeared to me unanswerable against a column standing alone. . . .

- “The column used as a form of monument has two advantages. First, it is a beautiful object—confessedly so. Secondly, it requires no study or thought; the formula being ready made to our hands.

- “I object, as regards the first of these advantages, that the beauty of a column, perfect as it is, is a relative beauty, and arises from its adaptation to the foundation on which it rests, and to the entablature which it is organized to sustain. The spread of the upper member of the capital calls for the entablature, cries aloud for it. The absence of that burden is expressive either of incompleteness, if the object be fresh and new, or of ruin if it bear the marks of age. The column is, therefore, essentially fractional—a capital defect in a monument, which should always be independent. I object to the second advantage as being one only to the ignorant and incapable. I hold the chief value of a monument to be this, that it affords opportunity for feeling, thought, and study, and that it not only occasions these in the architect, but also in the beholder.”

Images

Anonymous, “View of Bunker’s Hill,” in Gentleman’s Magazine 60, part 1 (February 1790): plate III, facing 140.

Nathaniel Currier after J. Fisher, View of Bunker Hill and Monument, June 17, 1843, c. 1843.

Anonymous, Boston Massachusetts. View of Bunker Hill Monument, Charles.[town], c. 1848.

Other Resources

Library of Congress Name Authority File

Bunker Hill website (National Park Service)

Notes

- ↑ John Zukowsky, “Monumental American Obelisks: Centennial Vistas,” Art Bulletin 58 (December 1976): 574, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Sarah J. Purcell, Sealed with Blood: War, Sacrifice, and Memory in Revolutionary America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010), 106, 164, view on Zotero.

- ↑ George Washington Warren, The History of the Bunker Hill Monument Association (Boston: James R. Osgood, 1877), 47, view on Zotero; see also Purcell 2010, 195–99, view on Zotero.

- ↑ John M. Bryan, Robert Mills: America’s First Architect (Princeton, NJ: Princeton Architectural Press, 2001), 204, view on Zotero; Pamela Scott, “Robert Mills and American Monuments,” in Robert Mills, Architect, ed. John M. Bryan (Washington, DC: American Institute of Architects Press, 1989), 133, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Henry T. Tuckerman, A Memorial of Horatio Greenough, Consisting of a Memoir, Selections from His Writings, and Tributes to His Genius (New York: G. P. Putnam & Co., 1853), 82, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Purcell 2010, 199–200; see also Nathalia Wright, “The Monument That Jonathan Built,” American Quarterly Observer 5 (1953): 167–71, view on Zotero.

- ↑ William W. Wheildon, Memoir of Solomon Willard, Architect and Superintendent of the Bunker Hill Monument (Boston: The Monument Association, 1865), 58–224, view on Zotero; see also Solomon Willard, Plans and Sections of the Obelisk on Bunker’s Hill, with the Details of Experiments Made in Quarrying the Granite (Boston: Charles Cook, 1843), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Kristen Heitert, Archeological Overview and Assessment of Bunker Hill Monument, Charlestown, Massachusetts, Submitted to the Northeast Region Archeology Program National Park Service, Public Archeology Laboratory, January 2009, 38–39, view on Zotero.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Weildon 1935, view on Zotero.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 H. M. Pierce Gallagher, Robert Mills, Architect of the Washington Monument, 1781–1855 (New York: Columbia University Press: 1935), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Tuckerman 1853, view on Zotero.