Difference between revisions of "Arboretum"

V-Federici (talk | contribs) m |

V-Federici (talk | contribs) m |

||

| Line 90: | Line 90: | ||

<gallery widths="170px" heights="170px" perrow="7"> | <gallery widths="170px" heights="170px" perrow="7"> | ||

| − | Image:0112.jpg|[[Anthony St. John Baker]], “[[View]] of the White House,” 1826, in ''Mémoires d’un voyageur qui se repose'' (1850). | + | Image:0112.jpg|[[Anthony St. John Baker]], “[[View]] of the White House,” 1826, in ''Mémoires d’un voyageur qui se repose'' (1850). The arboretum is visible on left side within the fence. |

</gallery> | </gallery> | ||

Latest revision as of 16:30, February 3, 2021

History

An arboretum was a botanic garden of trees, shrubs, and woody vines. Organized according to scientific or aesthetic principles, or a combination of these, arboreta were founded for public, private, and institutional purposes in America during the colonial and early national period. Some arboreta comprised collections of all indigenous trees while others were composed of a particular genus, such as pines (this type of arboretum was also called a pinetum). For example, the Pierce Brothers Arboretum in East Marlborough, Pennsylvania, was primarily an evergreen collection. Jane Loudon offered several organizing principles for both public and private gardens in Gardening for Ladies (1845). After the turn of the 19th century, when public gardens and civic beautification campaigns flourished, arboreta became increasingly popular. Planting and preserving trees were seen as a part of America’s need to plan for future generations, as George William Johnson discussed in A Dictionary of Modern Gardening (1847) (view text).

The White House arboretum [Fig. 1] was established during the administration of John Quincy Adams (1825–28), an ardent conservationist, exemplifying how political and economic motivations dovetailed with scientific ones. Adams was particularly interested in hardwood trees needed for shipbuilding; the economic necessity of safeguarding American trade and military interests made the preservation of hardwood forests a compelling political platform.

In his 1851 plan for the National Mall in Washington, DC, A. J. Downing called the area a “public museum of Trees” rather than an arboretum.[1] The description of his design, however, concurred exactly with the content of his other writings on arboreta. He planned to convert the whole Mall “into an extended landscape garden, to be. . . planted with specimens properly labelled, of all the varieties of trees and shrubs that flourish in this climate” [Fig. 2].[2] The parallel of the museum and the arboretum also was expressed in a statement in 1847 by J. Jay Smith, who was a frequent correspondent in Downing’s the Horticulturist (view text).

Scientific institutions were motivated to collect and study woody plants not only to add to the knowledge of the natural world, but also to classify and claim them as an American resource. Often associated with departments of botanical studies or schools of medicine, arboreta were founded at several of the early American schools and colleges, such as Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, New York, Haverford and Swarthmore Colleges in Pennsylvania, and Transylvania College in Lexington, Massachusetts. The medicinal properties of native and imported plants remained an essential part of medical training into the 20th century (see Botanic garden).

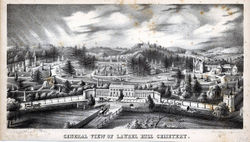

Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge and Laurel Hill Cemetery in Philadelphia were both planned to be tree and shrub collections under the supervision of local horticultural societies. Although Mount Auburn was not carried out as planned, Downing reported that Laurel Hill was laid out successfully by the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society as an arboretum.

In addition to public and institutional arboreta, private arboreta ornamented the grounds of many estates in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, where the wealthy displayed their collecting prowess and acumen. Collections of rare trees and shrubs were valuable not only for their scientific and ornamental interest but also for economic reasons. Although America’s forests seemed inexhaustible to many, plantations of trees were highly valued during the colonial period. In the early republican period when people began to think of themselves as Americans and not simply as English living abroad, figures such as Thomas Jefferson and later Downing championed American trees as a great source of pride and wealth for the young nation. Several years later, Jefferson decried the “unnecessary felling of a tree,” as a criminal act, “little short of murder.”[3] As Downing wrote, “Not to wish to know something of the character and history of trees, is as incomprehensible to us; as not to desire a knowledge of Niagara.”[4]

—Therese O’Malley

Texts

Usage

- Dearborn, H. A. S., 1832, describing Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, MA (quoted in Harris 1832: 65)[5]

- “On the southeastern and northeastern borders of the tract can be arranged the nurseries, and portions selected for the culture of fruit-trees and esculent vegetables, on an extensive scale; there may be arranged the Arboretum, the Orchard, the Culinarium, Floral departments, Melon grounds, and Strawberry beds, and Green houses.”

- Kirkbride, Thomas S., 1845, describing the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane, Philadelphia (quoted in Hawkins 1991: 105–6)[6]

- “ . . . it would be easy in a few years to have within our enclosure, a specimen of every tree that will live in this climate, and I know of no spot near Philadelphia, where a complete arboretum could be established with less trouble, or be a subject of greater interest or more utility than upon the 41 acres which compose our pleasure ground.”

- Downing, A. J., December 31, 1846, in a letter to Thomas P. Barton, describing Montgomery Place, country home of Mrs. Edward (Louise) Livingston, Dutchess County, NY (quoted in Haley 1988: 21)[7]

- “I am delighted to learn that you are about to add to the great charms of Montgomery Place by the formation of an arboretum. How few persons there are yet in this country who know any thing of the individual beauty of even our own forest trees! I wish you success in so laudable an undertaking.”

- Downing, A. J., October 1847, “A Visit to Montgomery Place,” describing the country home of Mrs. Edward (Louise) Livingston, Dutchess County, NY (Horticulturist 2: 160)[8]

- “Among those more worthy of note, we gladly mention an arboretum, just commenced on a fine site in the pleasure grounds, set apart and thoroughly prepared for the purpose. Here a scientific arrangement of all the most beautiful hardy trees and shrubs, will interest the student, who looks upon the vegetable kingdom with a more curious eye than the ordinary observer.” [Fig. 3]

- Darlington, William, 1849, describing the Peirce Brothers Arboretum, East Marlborough, PA (1849: 22)[9]

- “About the year 1800, also, the brothers JOSHUA and SAMUEL PEIRCE, of East Marlborough, began to adorn their premises by tasteful culture and planting; and they have produced an Arboretum of evergreens, and other elegant forest trees, which is certainly unrivalled in Pennsylvania, and probably not surpassed in these United States.”

- Downing, A. J., July 1849, “Public Cemeteries and Public Gardens,” describing Laurel Hill Cemetery, Philadelphia (Horticulturist 4: 10)[10]

- “Laurel Hill is especially rich in rare trees. We saw, last month, almost every procurable species of hardy tree and shrub growing there—among others, the Cedar of Lebanon, the Deodar Cedar, the Paulownia, the Araucaria, etc. Rhododendrons and Azaleas were in full bloom; and the purple Beeches, the weeping Ash, rare Junipers, Pines, and deciduous trees were abundant in many parts of the grounds. Twenty acres of new ground have just been added to this cemetery. It is a better arboretum than can easily be found elsewhere in the country.” [Fig. 4]

Citations

- Loudon, Jane, 1845, Gardening for Ladies (1845: 120)[11]

- “ARBORE’TUM.—A collection of trees and shrubs, containing only one or two plants of a kind, arranged together, according to some system or method. The most common arrangement is that of the Natural System; but the plants in an arboretum may be placed together according to the countries of which they are natives; according to the soil in which they grow; or according to their sizes and habits, or time of leafing, or flowering. In all small villa residences an arboretum is the most effectual means of procuring a maximum of enjoyment in a minimum of space, as far as trees and shrubs are concerned. To render an arboretum useful and interesting, each tree and shrub should be named.”

- Johnson, George William, 1847, A Dictionary of Modern Gardening (1847: 62–63)[12]

- “ARBORETUM is a collection of trees and shrubs capable of enduring exposure to our climate. These are usually arranged in genera according to their precedence in the alphabet; or in groups conformably to the Jussieuean system; and whichever is adopted it is quite compatible with an attention to facility of access by means of walks, as well as to picturesque effect.

- “It is an evil growing out of the frequent change in the ownership of estates, that most proprietors are indisposed to plant for posterity; consequently we see but few grounds laid out with a view to permanent improvement. Those who plant are anxious themselves to reap the fruits of their exertions, not knowing, and consequently careless, who shall succeed them—where landed property is, by entail, transmitted from generation to generation, family pride, and the love of distinction, ensure every improvement being made in a permanent form—thus have been created the magnificent parks of Europeans, and their stately mansions. Our American system deprives us of such monuments of taste—but we can bear the deprivation, seeing the greater good produced thereby.” back up to History

- Smith, J. Jay, July 1847, “Arboricultural Gossip” (Horticulturist 2: 29)[13]

- “With all our truly fine sylvan scenery, there are none of your readers, who have not seen the thing for themselves, that know how properly to rate the enjoyment of those collections of fine ornamental trees which the English make at their country places, under the name of ARBORETUMS. It is for a country residence, what a museum, or rich collection in natural history or art, is for a town house; a source of interest perpetual and unvarying. Many a person (and there are, I am sorry to say, such in all countries,) to whom trees are only trees— that is, green things in the landscape, in which they perceive little distinction—are immediately struck and interested in a country place by an arboretum— that is, a collection of trees properly arranged on a large lawn, each genus, with all its varieties, near each other, so as to show off their contrasts and individualities to the highest advantage. Such a park or lawn soon seizes upon the mind and attracts it; almost insensibly one is led to compare forms and developments; and very quickly he who knew little and cared less about trees, finds himself acquiring the acquaintance of the most distinguished botanical families!” back up to History

- Webster, Noah, 1848, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1848: 65)[14]

- “ARBORETUM, n. A place in a park, nursery, &C, in which a collection of trees, consisting of one of each kind, is cultivated. Brande"

Images

Associated

E. J. Pinkerton, General View of Laurel Hill Cemetery, 1844.

A. J. Downing, Plan Showing Proposed Method of Laying Out the Public Grounds at Washington, 1851. Manuscript copy by Nathaniel Michler, 1867.

Attributed

Anthony St. John Baker, “View of the White House,” 1826, in Mémoires d’un voyageur qui se repose (1850). The arboretum is visible on left side within the fence.

Notes

- ↑ Quoted in Wilcomb E. Washburn, “Vision of Life for the Mall,” AIA Journal 47 (March 1967): 52–59, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Quoted in David Schuyler, “The Washington Park and Downing’s Legacy to Public Landscape Design,” in Prophet with Honor: The Career of Andrew Jackson Downing, 1815–1852 (Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks, 1989), 291–311, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Margaret Bayard Smith, The First Forty Years of Washington Society, ed. Gaillard Hunt (New York: Charles Scribner’s, 1906), 394, view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. Downing, “Impressions of Chatsworth,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 1, no. 7 (January 1847): 301, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thaddeus William Harris, A Discourse Delivered before the Massachusetts Horticultural Society on the Celebration of Its Fourth Anniversary, October 3, 1832 (Cambridge, MA: E. W. Metcalf, 1832), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Kenneth Hawkins, “The Therapeutic Landscape: Nature, Architecture, and Mind in Nineteenth-Century America” (PhD diss., University of Rochester, 1991), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Jacquetta M. Haley, ed., Pleasure Grounds: Andrew Jackson Downing and Montgomery Place (Tarrytown, NY: Sleepy Hollow Press, 1988), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Alexander Jackson Downing, “A Visit to Montgomery Place,” The Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 2, no. 4 (October 1847): 153–60, view on Zotero.

- ↑ William Darlington, Memorials of John Bartram and Humphry Marshall: With Notices of Their Botanical Contemporaries (Philadelphia: Lindsay & Blakiston, 1849), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Andrew Jackson Downing, “Public Cemeteries and Public Gardens,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 4, no. 1 (July 1849): 9–12, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Jane Loudon, Gardening for Ladies; and Companion to the Flower-Garden, ed. A. J. Downing (New York: Wiley & Putnam, 1845), view on Zotero.

- ↑ George William Johnson, A Dictionary of Modern Gardening, ed. David Landreth (Philadelphia: Lea and Blanchard, 1847), view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. Jay Smith, “Arboricultural Gossip,” Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste 2, no. 1 (July 1847): 28–31, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language. . . Revised and Enlarged by Chauncey A. Goodrich. . . (Springfield, MA: George and Charles Merriam, 1848), view on Zotero.