Difference between revisions of "Dovecote/Pigeon house"

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

==History== | ==History== | ||

| − | [[File:0631.jpg|thumb|left|Fig. 1, Anonymous, Dovecote at Shirley on the James, n.d., in Alice B. Lockwood, Gardens of Colony and State (1934), vol. 2, p. 80.]] | + | [[File:0631.jpg|thumb|left|Fig. 1, Anonymous, Dovecote at Shirley on the James, n.d., in Alice B. Lockwood, ''Gardens of Colony and State'' (1934), vol. 2, p. 80.]] |

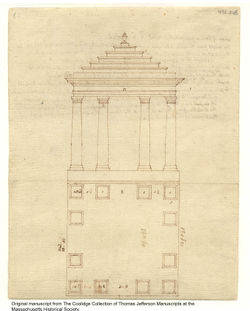

A dovecote, dovehouse, or pigeon house, was a structure for breeding and housing domestic pigeons. <ref>A pigeon is a bird in the order of Columbae, of which there are a great number of species. Several of the smaller species of pigeons are known as doves, including the stock dove, ring-dove, and turtledove.</ref> Because pigeons provided meat and eggs as well as fertilizer, dovecotes were constructed to ensure the birds’ safety and to aid in the retrieval of eggs. A key element in their design was an elevated position for roosting niches. Some dovecotes consisted of boxes mounted on the side of a building or placed on poles, as described in 1842 by Edward James Hooper. Others were free-standing structures, such as the outbuilding noted by William Fitzhugh in 1686. Still others were located on top of another structure, as in the 1736 South Carolina plantation advertisement listing a dove-house above a brick necessary. While all had multiple entrances and roosting niches, the designs for dovecotes ranged from simple utilitarian structures to more elaborate designs, such as the circular brick dovecote at Shirley on the James River [Fig. 1] and the neoclassical design for a temple and dovecote at Monticello [Fig. 2]. Jefferson’s design, which was never executed, proposed access holes in the frieze for the birds to come and go. <ref>William Howard Adams, ed., ''The Eye of Thomas Jefferson'' (Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1976), 333. [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/IWQT8BPV view on Zotero.]</ref> | A dovecote, dovehouse, or pigeon house, was a structure for breeding and housing domestic pigeons. <ref>A pigeon is a bird in the order of Columbae, of which there are a great number of species. Several of the smaller species of pigeons are known as doves, including the stock dove, ring-dove, and turtledove.</ref> Because pigeons provided meat and eggs as well as fertilizer, dovecotes were constructed to ensure the birds’ safety and to aid in the retrieval of eggs. A key element in their design was an elevated position for roosting niches. Some dovecotes consisted of boxes mounted on the side of a building or placed on poles, as described in 1842 by Edward James Hooper. Others were free-standing structures, such as the outbuilding noted by William Fitzhugh in 1686. Still others were located on top of another structure, as in the 1736 South Carolina plantation advertisement listing a dove-house above a brick necessary. While all had multiple entrances and roosting niches, the designs for dovecotes ranged from simple utilitarian structures to more elaborate designs, such as the circular brick dovecote at Shirley on the James River [Fig. 1] and the neoclassical design for a temple and dovecote at Monticello [Fig. 2]. Jefferson’s design, which was never executed, proposed access holes in the frieze for the birds to come and go. <ref>William Howard Adams, ed., ''The Eye of Thomas Jefferson'' (Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1976), 333. [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/IWQT8BPV view on Zotero.]</ref> | ||

Revision as of 13:56, February 23, 2017

(Dovecoat, Dove-cot, Dove house, Pidgeon house)

See also: Aviary

History

A dovecote, dovehouse, or pigeon house, was a structure for breeding and housing domestic pigeons. [1] Because pigeons provided meat and eggs as well as fertilizer, dovecotes were constructed to ensure the birds’ safety and to aid in the retrieval of eggs. A key element in their design was an elevated position for roosting niches. Some dovecotes consisted of boxes mounted on the side of a building or placed on poles, as described in 1842 by Edward James Hooper. Others were free-standing structures, such as the outbuilding noted by William Fitzhugh in 1686. Still others were located on top of another structure, as in the 1736 South Carolina plantation advertisement listing a dove-house above a brick necessary. While all had multiple entrances and roosting niches, the designs for dovecotes ranged from simple utilitarian structures to more elaborate designs, such as the circular brick dovecote at Shirley on the James River [Fig. 1] and the neoclassical design for a temple and dovecote at Monticello [Fig. 2]. Jefferson’s design, which was never executed, proposed access holes in the frieze for the birds to come and go. [2]

Conclusions regarding the chronology and regional use of the term “dovecote,” particularly in relation to pigeon house, are difficult to make given the limited sample of references and images. The term “pigeon house” was defined synonymously with dovecote by Noah Webster (1828) and J. C. Loudon (1838). Moreover, the term “pigeon house” in American usage seems to have been increasingly preferred over dovecote during the course of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries by such writers as Col. Landon Carter (1764) and Martha Ogle Forman (1819). [3] The term “dovecote” was not abandoned altogether however, as evidenced by Frederick Law Olmsted’s 1852 description of Riversdale, George and Rosalie Stier Calvert’s estate in Maryland: “The kept grounds are very limited, and in simple but quiet taste. . . . There is a fountain, an ornamental dove-coat, and ice-house.” [4]

The number of American references is small, and they derive mostly from the south and mid-Atlantic. Charles Willson Peale’s mention of his pigeon house at Belfield was one of the more colorful accounts of the feature. He wrote in 1814 that “once a pair of Squabs was taken to the Kitchen, but the Parent came after them and alighting on the Kitchen window, Mrs. Peale’s delicate feelings could not suffer them to be killed and accordingly they were returned to the Pidgeon-house.”

-- Elizabeth Kryder-Reid

Texts

Usage

- Fitzhugh, William, 22 April 1686, describing Eagle’s Nest, estate of William Fitzhugh, Stafford County, Va. (quoted in Davis 1963: 175) [5]

- “the Plantation where I now live contains a thousand Acres . . . ground & fencing, . . . upon the same land is my own Dwelling house ...& all houses for use well furnished with brick Chimneys, four good Cellars, a Dairy, Dovecoat, Stable, Barn, Hen house Kitchen & all other conveniencys, & all in a manner new.”

- Anonymous, 1736, describing in the South Carolina Gazette Goose Creek, estate of Peter Smith, Berkeley County, S.C. (quoted in Lounsbury 1994: 117) [6]

- “[The plantation to be sold contains] a necessary-house neatly built, and above it a dove-house with nests for 50 pair of pigeons.”

- Anonymous, 5 January 1740, describing a plantation for rent in Charleston, S.C. (South Carolina Gazette)

- “On Tuesday the 21st of February next, will be exposed to Sale at publick Outcry, at my Plantation near the Brick Church in the Parish of St. Thomas. . . . And the late Landgrave Daniel’s Plantation upon Daniel’s Island, now in my Possession with a large Brick House . . . and a Brick Dove-House thereon, is to be let.”

- Carter, Landon, 1764, describing property in Richmond County, Va. (quoted in Lounsbury 1994: 271) [6]

- “Colo. Tayloe’s Ralph [was] sent back here to cut my dishing capstones for my Pigeonhouse posts to keep down the rats.”

- Peale, Charles Willson, 30 October 1814, describing Belfield, estate of Charles Willson Peale, Germantown, Pa. (Miller, Hart, and Ward, eds., 2000: 5:382–83) [7]

- “once a pr. of squabs was taken to the Kitchen, but the Parent came after them and alighting on the Kitchen window, Mrs. Peale’s delicate feelings could not suffer them to be killed and accordingly they were returned to the Pidgeon-house.”

- Forman, Martha Ogle, 1819 and 1823, describing Rose Hill, home of Martha Ogle Forman, Baltimore County, Md. (1976: 76, 159) [8]

- “[11 February 1819] Planted potatoes in the front lot east of the Pigeon house....

- “[8 May 1823] Rachel finished whitewashing the garden poles, the Pigeon house and the fence round the lawn.”

Citations

- Johnson, Samuel, 1755, A Dictionary of the English Language (2:n.p.) [9]

- “P’IGEON. n.s. [pigion, Fr.] A fowl bred in cots or a small house: in some places called dovecote.”

- Hale, Thomas, 1758, A Compleat Body of Husbandry (2:104) [10]

- “I have spoke often to farmers to recommend setting up of dovecoats; but have found it difficult to make them listen to me. While they have bought pigeons dung at a large price, and fetch’d it from a great distance, they have still been backward to think of keeping pigeons for their supply. There is a superstition among them, that it is unlucky to set up a new dovecoat: this has come from father to son, and they persuade themselves it would certainly be follow’d by death in the family.”

- Webster, Noah, 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (n.p.) [11]

- “DOVE-COT, n. A small building or box in which domestic pigeons breed. . . .

- “DOVE-HOUSE, n. A house or shelter for doves. . . .

- “PIG’EON, n....

- “The domestic pigeon breeds in a box, often attached to a building, called a dovecot or pigeon-house. The wild pigeon builds a nest on a tree in the forest.”

- Loudon, J. C., 1838, The Suburban Gardener (p. 710) [12]

- “The Pigeon-house, or Dovecot.—The common pigeon, of which there are many varieties, may be kept in a small house, in a manner similar to common fowls; but it succeeds better in buildings somewhat elevated, or in low buildings in which the place of entrance is made in the roof; because pigeons fly higher than any other domesticated birds. A very convenient situation is a loft over some other building, or when there are various out-buildings, a turret may be added where it will have a good effect in an architectural point of view, and the interior turned into a place for pigeons.”

- Hooper, Edward James, 1842, The Practical Farmer, Gardener and Housewife (pp. 317–18) [13]

- “PIGEONS. . . . A pretty object in a poultry yard is a wooden structure or dovecote raised from the ground on one or more high posts.”

- Webster, Noah, 1848, An American Dictionary of the English Language (p. 363) [14]

- “DOVE’-COT, (duv’-kot,) n. A small building or box, raised to a considerable hight [sic] above the ground, in which domestic pigeons breed.”

Images

Inscribed

- 0555.jpg

Anonymous, Plat of 117 Broad Street, Charleston, 1797.

Attributed

Thomas Jefferson, Design for a garden temple and dovecote at Monticello, c. 1778.

J. C. Loudon, "Wire-cages," in An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1826), p. 347, fig. 301.

Notes

- ↑ A pigeon is a bird in the order of Columbae, of which there are a great number of species. Several of the smaller species of pigeons are known as doves, including the stock dove, ring-dove, and turtledove.

- ↑ William Howard Adams, ed., The Eye of Thomas Jefferson (Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1976), 333. view on Zotero.

- ↑ Carl R. Lounsbury, ed., An Illustrated Glossary of Early Southern Architecture and Landscape (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Frederick Law Olmsted, A Journey in the Seaboard Slave States: With Remarks on their Economy (New York: Dix & Edwards; London: Sampson Low, 1856), 6. view on Zotero.

- ↑ Richard Beale Davis, William Fitzhugh and His Chesapeake World, 1676-1701 (Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press, 1963), view on Zotero.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Carl R. Lounsbury, ed., An Illustrated Glossary of Early Southern Architecture and Landscape (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Lillian B. Miller et al, eds., The Selected Papers of Charles Willson Peale and His Family: Charles Willson Peale: Artist in Revolutionary America, 1735-1791. Vol. 1; Charles Willson Peale, Artist as Museum Keeper, 1791-1810. Vol 2, Pts. 1-2; The Belfield Farm Years, 1810-1820. Vol. 3; The Autobiography of Charles Willson Peale. Vol. 5. (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1983–2000), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Martha Ogle Forman, Plantation Life at Rose Hill: The Diaries of Martha Ogle Forman, 1814-1845 (Wilmington, Del.: Historical Society of Delaware, 1976), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Samuel Johnson, A Dictionary of the English Language: In Which the Words Are Deduced from the Originals and Illustrated in the Different Significations by Examples from the Best Writers, 2 vols (London: W. Strahan for J. and P. Knapton, 1755), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Hale, A Compleat Body of Husbandry Containing Rules for Performing, in the Most Profitable Manner, the Whole Business of the Farmer and Country Gentleman, 2nd edn, 4 vols (London: T. Osborne, 1758), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language, 2 vols (New York: S. Converse, 1828)

- ↑ J. C. Loudon (John Claudius), The Suburban Gardener, and Villa Companion (London: Longman et al, 1838), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Edward James Hooper, The Practical Farmer, Gardener and Housewife, or Dictionary of Agriculture, Horticulture, and Domestic Economy (Cincinnati, Ohio: George Conclin, 1842), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language... Revised and Enlarged by Chauncey A. Goodrich.... (Springfield, Mass.: George and Charles Merriam, 1848), view on Zotero.