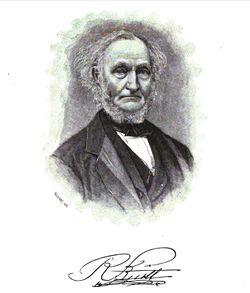

Robert Buist

Robert Buist (November 14, 1805–July 18, 1880) was a Scottish-born nursery- and seedsman based in Philadelphia. Through his businesses and his garden manuals, Buist became one of the most influential figures in American horticulture during the 19th century.

History

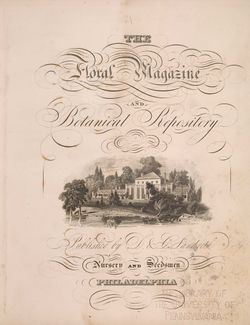

Robert Buist was born in Cupar Fyfe, Scotland, on November 14, 1805 [Fig. 1]. Though little is known about his early life, he is believed to have trained as a gardener with William McNab, who served from 1810 until 1848 as the Principal Gardener of the Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh. McNab was known for his careful relocation of the garden to its present site at Inverleith, with much of the transfer of plants occurring between 1821 and 1823, possibly during Buist’s tenure there.[1] Buist later moved to Derbyshire to work in the gardens of General Charles Stanhope, the 3rd Earl of Harrington, at Elvaston Castle, before immigrating to the United States in August 1828.[2] On arriving in Philadelphia, Buist quickly immersed himself in its horticultural community, working briefly at David Landreth’s nursery in Moyamensing before becoming the gardener of Henry Pratt’s Lemon Hill [Fig. 2]. In June 1829 he participated in the first exhibition of the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, with which he maintained a lifelong affiliation.[3]

By September 1830 Buist had left his post at Lemon Hill to go into business with the nurseryman Thomas Hibbert, whose greenhouses were located on 13th Street between Lombard and Cedar (now South) Streets. As part owner, Buist had a degree of autonomy that he likely lacked in his earlier positions—he described his situation at Landreth’s, where he was relegated to hoeing weeds, as especially dismal.[4] Within his first year of joining Hibbert, the pair considerably expanded the nursery by purchasing Bernard M’Mahon’s former botanic garden, Upsal, and Buist travelled back to Scotland and England “to make arrangements . . . to receive continued supplies of all kinds of new and desirable Plants and Flowers.”[5] While abroad, Buist also paid a visit to J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon—the preeminent horticulturist in England—and returned to Philadelphia in November 1831 with his longtime friend, the architect John Notman.[6] Buist’s travels yielded some fine stock, particularly of dahlias, which was described in the May 15, 1832, issue of the National Gazette and Literary Register as boasting “upwards of fifty of the most distinct [dahlias] in color and the largest in size; some of them Glob[e]-flowered, and Anemone-flowered, which are considered beautiful and rare.”[7]

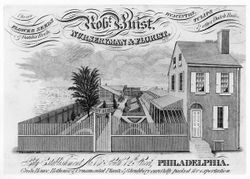

The partnership of Hibbert & Buist was successful but not long-lived; Thomas Hibbert died on May 11, 1833, just a year after the National Gazette’s report.[8] Hibbert’s widow determined to carry on her husband’s business while Buist struck out on his own, using part of the Hibbert & Buist stock to open his own independent nursery on 12th Street [Fig. 3] and a seed warehouse on Chestnut Street.[9] “R. Buist’s Exotic Nursery” featured a greenhouse 150 feet in length, 18 feet wide, and 15 feet high, that was divided into five compartments to accommodate the different plants he stocked. The front compartment was referred to as the “New-Holland House” and featured various species of Banksia—which Buist likely learned to cultivate while working with McNab, who specialized in the plant[10]—and was followed by the hothouse or stove, which featured the canary bird flower (Tropaeolum peregrinum), petunias, ficuses, and other rare plants. Toward the rear Buist created compartments dedicated to specific types of flower, including the Geranium House, the Camellia House, and the Rose House.[11]

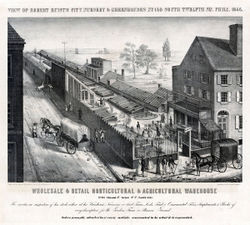

Buist’s nursery and seed warehouse throve finely during the 1830s and 1840s, allowing him to expand his business significantly. By 1837 he had built a separate camellia house and small stove at 12th Street [Fig. 4], and by 1849 he had established a nursery for fruit and ornamental trees southwest of Philadelphia, called Rosedale, where he eventually consolidated all but his seed business in 1850.[12] During these decades Buist remained an active member of the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, gaining recognition for his introduction of verbenas and the poinsettia to North America, and helped found the American Pomological Society.[13] He also authored three frequently reprinted gardening manuals—the American Flower Garden Directory (1832), the Rose Manual (1844), and the Family Kitchen Gardener (1847)—which helped make him one of the most recognizable figures in American horticulture.[14]

Even in the midst of these professional accomplishments, Buist suffered various familial challenges in the 1840s. His wife, Jane Menzies Buist—the mother of his sons, John and Robert Jr.—died from tuberculosis on July 12, 1840, and Buist remarried shortly after to Ellen Chambers (née Stephens), with whom he had one daughter.[15] During this period he also lodged two lawsuits against his brother William, who had established a nursery in Washington, DC, and who may have tried to bolster his business by trading on Robert’s success.[16] Though the court cases remain obscure, the results are not: in September 1847 Alexander Hunter, the marshal of Washington, DC, seized William’s nursery “to satisfy judicials . . . in favor of Robert Buist against said Wm. Buist.” Bankrupt and out of business, William died in July 1850.[17] Robert’s home and business, by contrast, was full to brimming at this time: according to the 1850 federal census, taken in July that year, Buist was supporting not only his new wife, stepdaughter, daughter, and son Robert Jr., but also members of his wife’s extended family and about 20 servants, laborers, and gardeners, all from Scotland and Ireland.[18]

The number of gardeners and laborers Buist brought over from Britain and Ireland greatly enhanced botanical knowledge in the United States. His service to American horticulture was described as twofold—Colonel Marshall P. Wilder of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society noted that “he not only introduced rare plants, but rare men.”[19] Buist remained active in the plant trade throughout the 1850s, 60s, and 70s, and the value of his businesses increased considerably: the 1850 census notes the “value of property owned” as $35,000, and the 1860 census indicates a personal worth estimated at $45,000, exclusive of the impressive $125,000 Buist owned in real estate.[20] It may have been his financial success that allowed Buist to relinquish control of the seed warehouse to his younger son, Robert Jr., by September 1861, and to direct his attention largely to floriculture. Robert Buist fully retired from the nursery business in 1876 and died four years later, at the age of 74.[21]

—Elizabeth Athens

Texts

- Buist, Robert, 1841, The American Flower Garden Directory, 2nd ed. (1841: 9)[22]

“The French partially adopt the . . . [Italian] system, interspersing it with parterres and figures of statuary work of every character and description. When such is well designed and neatly executed, it has a lively and interesting effect; but now the refined taste says these vagaries are too fantastic, and entirely out of place.”

- Buist, Robert, 1841, The American Flower Garden Directory, 2nd ed. (1841: 9–10)

“A late writer says of Dutch gardening, that it ‘is rectangular formality’: they take great pride in trimming their trees of yew, holly, and other evergreens, into every variety of form, such as mops, moons, halberds, chairs &c. In such a system it is indispensable to order that the compartments correspond in formality, nothing being more offensive to the eye than incongruous mixtures of character.”

- Buist, Robert, 1841, The American Flower Garden Directory, 2nd ed. (1841: 10–11)

“. . . if access to a spring can be obtained, it will prove a desideratum in completing the whole: it can be available for a fish-pond or an acquariam [sic], or can be converted into a swamp for the cultivation of many of our most beautiful and interesting native plants.”

- Buist, Robert, 1841, The American Flower Garden Directory, 2nd ed. (1841: 11)

“For perspicuity, admit that the area to be enclosed [for a flower garden] should be from one to three acres, a circumambient walk should be traced at some distance within the fence, buy which the whole is enclosed; the inferior walks should partly circumscribe and intersect the general surface in an easy serpentine and sweeping manner, and at such distances as would allow an agreeable view of the flowers when walking for exercise. Walks may be in breadth from three to twenty feet, although from four to ten feet is generally adopted . . . covered with gravel, and then firmly rolled with a heavy roller. . . .”

- Buist, Robert, 1841, The American Flower Garden Directory, 2nd ed. (1841: 11–12)

“But, in commencing these operations, a design [for the flower garden] should be kept in view that will tend to expand, improve, and beautify the situation; not, as we too frequently see it, the parterre and borders with narrow walks up to the very household entrance: such is decidedly bad taste, unless compelled for want of room. . . . The outer margin of the [flower] garden should be planted with the largest trees and shrubs: the interior arrangement may be in detached groups of shrubbery and parterres.”

- Buist, Robert, 1841, The American Flower Garden Directory, 2nd ed. (1841: 12)

“In some secluded spot rock-work or a fountain, or both, may be erected; the foundation of the former should consist of mounds of earth, which will answer the purpose of more solid erections, and will make the stones go farther: rocks of the same kind and colour should be placed together, and the greatest possible variety of character, size and form, should be studied, the whole showing an evident and well defined connexion. These erections generally are stiff artificial disjointed masses, and often decorated with plants having no affinity to their arid location.”

- Buist, Robert, 1841, The American Flower Garden Directory, 2nd ed. (1841: 13)

“All the large divisions [of a flower garden] should be intersected by small alleys, or paths, about one and a half or two feet wide.”

- Buist, Robert, 1841, The American Flower Garden Directory, 2nd ed. (1841: 13)

“When there is not a green-house attached to the flower garden, there should be at least a few sashes of framing or a forcing pit to bring forward early annuals, &c., for early blooming. These should be situate [sic] in some spot detached from the garden by a fence of Roses, trained to trellises, Chinese Arbour Vitae, Privet, or even Maclura makes excellent fences. . . .”

- Buist, Robert, 1841, The American Flower Garden Directory, 2nd ed. (1841: 20)

“Thick masses of shrubbery, called thickets, are sometimes wanted. In these there should be plenty of evergreens. A mass of deciduous shrubs has no imposing effect during winter.”

- Buist, Robert, 1841, The American Flower Garden Directory, 2nd ed. (1841: 31)

“BOX EDGINGS.

“May be planted any time this month [March], or beginning of next, which in most seasons will be preferable. We will give a few simple directions how to accomplish the work. In the first place, dig over the ground deeply where the edging is intended to be planted, breaking the soil fine, and keeping it to a proper height, namely, about one inch higher than the side of the walk; but the taste of the operator will best decide, according to the situation.”

- Buist, Robert, 1841, The American Flower Garden Directory, 2nd ed. (1841: 32)

Grass verges for walks and borders, although frequently used, are, by no means, desirable, except where variety is required; they are the most laborious to keep in order, and at best are inelegant, and the only object in their favor is, there being everywhere accessible.

- Buist, Robert, 1841, The American Flower Garden Directory, 2nd ed. (1841: 145, 148)

“ON THE CONSTRUCTION OF A HOT-HOUSE. . . .

“Site and Aspect.—The house should stand on a situation naturally dry, and, if possible, sheltered from the north-west, and clear from all shade on the south, east, and west, so that the sun may at all times act effectually upon the house. The standard principle, as to aspect, is to set the front directly to the south. Any deviation from that point should incline to the east.

“Dimensions.—The length may be from ten feet upward; if beyond forty feet, the number of fires and flues are multiplied. The medium width is from twelve to sixteen feet. . . .

“Bark Pit.—We consider such an erection in the centre of a hot-house a nuisance, and prefer a stage, which may be constructed according to taste. It should be made of the best Carolina pine, leaving a passage all round, to cause free circulation of air.”

Images

Notes

- ↑ “Principal Gardeners—William McNab,” Notes from the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh 3, part 15 (March 1908): 303, 306–7, 319, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Thomas Meehan, “Robert Buist,” Gardener’s Monthly and Horticulturist 22, no. 264, ed. Thomas Meehan (December 1880): 372, view on Zotero. Meehan’s 1880 obituary of Buist is perhaps the most fulsome single description of his life and work. U. P. Hedrick discusses Buist’s relation to other nursery- and seedsmen of the period; see his History of American Horticulture in America to 1860 (1950; repr. Portland, OR: Timber Press, 1988), 248, view on Zotero.

- ↑ James Boyd, A History of the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, 1827–1927 (Philadelphia: Printed for the Society, 1929), 36, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Meehan 1880, 372, view on Zotero.

- ↑ “Hibbert & Buist,” Poulson’s American Daily Advertiser (September 17, 1831): 4, view on Zotero.

- ↑ For Buist’s visit to Loudon, see William Wynne, “Some Account of the Nursery Gardens and the State of Horticulture in the Neighbourhood of Philadelphia,” Gardener’s Magazine, and Register of Rural & Domestic Improvement 8, no. 30, ed. J. C. Loudon (June 1832): 273, view on Zotero. Buist would be essential in securing Notman’s 1856 commission for the entrance gate of Philadelphia’s Mount Vernon Cemetery, where Buist was treasurer. Constance Greiff, John Notman, Architect: 1810–1865, exh. cat. (Philadelphia: The Athenaeum of Philadelphia, 1979), 18, 215, view on Zotero.

- ↑ National Gazette and Literary Register (May 15, 1832): 2, view on Zotero.

- ↑ “Died,” Philadelphia Inquirer (May 13, 1833): 2, view on Zotero.

- ↑ C. M. H. [C. M. Hovey], “Notices of Some of the Gardens and Nurseries in the Neighborhood of New York and Philadelphia,” American Gardeners’ Magazine, and Register of Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Horticulture and Rural Affairs 1, no. 6, ed. C. M. Hovey (June 1835): 203, view on Zotero. Buist’s nursery extended from 12th Street along Cedar, abutting the Hibbert nursery on 13th Street.

- ↑ “Principal Gardeners” 1908, 303, 307–8, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Descriptions of the nursery layout can be found in the National Gazette and Literary Register (December 19, 1833): 2, and Hovey 1835, 203–6, view on Zotero.

- ↑ [C. M. Hovey], “Notes on Some of the Nurseries and Private Gardens in the Neighborhood of New York and Philadelphia, visited in the early part of the month of March, 1837,” Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs 3, no. 6, ed. C. M. Hovey (June 1837): 202, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Meehan 1880, 373, view on Zotero.

- ↑ All three books went through numerous editions and reprints: American Flower Directory went through 6 editions and at least 19 reprints between 1832 and 1865; the Rose Manual went through 4 editions between 1844 and 1854; and the Family Kitchen Gardener went through at least 19 reprints between 1847 and 1867. For a discussion of Buist’s importance as an author, see Hedrick 1988, 481–2, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Jane Menzies’s death is noted in the July 14, 1840, issue of the National Gazette. Her cause of death was “pthisis pulmonalis”; see “Pennsylvania, Philadelphia City Death Certificates, 1803–1915,” FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:JKS8-DJM : March 8, 2018), Jane Buist, July 13, 1840; Philadelphia City Archives and Historical Society of Pennsylvania, PA; FHL microfilm 1,976,401.

- ↑ William Buist’s Washington, DC, nursery was advertised as early as May 1837 and was the subject of a notice in the Magazine of Horticulture in 1842; see the Daily Globe (May 3, 1837): 2, view on Zotero, and “Notes made during a visit to New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington, and intermediate places, from August 8th to the 23rd, 1841,” Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs 8, no. 4, ed. C. M. Hovey (April 1842): 123–25, view on Zotero.

- ↑ “Marshal’s Sale,” Daily Union (September 22, 1847): 2, view on Zotero, and “Deaths,” Daily National Intelligencer (July 6, 1850): 4, view on Zotero.

- ↑ “United States Census, 1850,” FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:M4CD-WP3 : April 12, 2016), Robert Buist, Kingsessing, Philadelphia, PA, United States; citing family 93, NARA microfilm publication M432 (Washington, DC: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.).

- ↑ Quoted in Meehan 1880, 374, view on Zotero.

- ↑ See “United States Census, 1850,” and “United States Census, 1860,” FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MXRX-SZR : December 13, 2017), Robert Buist, 1860.

- ↑ Meehan 1880, 373, view on Zotero. By September 1861, the proprietor of 922 Market Street—where Buist had eventually relocated his seed warehouse from Chestnut Street—was identified as Robert Buist Jr. See The Press (September 2, 1861): 3, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Robert Buist, The American Flower Garden Directory, 2nd ed. (Philadelphia: Carey and Hart, 1841), view on Zotero.