Plot/Plat

See also: Walk, Wilderness

Discussion

Plot, according to many lexicographers, was synonymous with plat. Noah Webster, for example, in 1828, used “plat” (“or small extent of ground”) to define “plot” and further indicated that the latter term held at least four distinct meanings. The first two definitions of the term—a small extent of ground or garden and an executed design of plant material—are well documented in textual and visual materials relating to the designed landscape in America. The third and fourth definitions, relating to survey plans, are less pertinent to landscape-design vocabulary and, therefore, appear less frequently in the material of our study. Even so, these latter references were still used occasionally, as indicated by Charles Willson Peale’s use of the term in 1810 to describe the plan that he had drawn of his property and by William H. Ranlett’s 1849 designation of a plan as “a protracted ground plot.”

In its first two definitions, plot referred to property divisions, which ranged in size from quarters of a garden to house lots or even larger portions of property. Used to describe a particular area of ground, the term “plot” relates closely to “plat” and, in general usage, the terms were nearly interchangeable. Timothy Dwight, in 1796, used “plat” to describe the combined lots of a New England town, while Ranlett, in 1849, used “plot” to describe the ideal layout of a village subdivided into lots [Fig. 1]. Plat, however, often had the added connotation of topographic flatness, a characteristic not necessarily associated with plot.

When used to indicate house lots, plots were typically rectangular in form, as indicated by William Strachey (1612) and Ranlett. But plots could take on a variety of forms in correspondence with their use as orchards, vineyards, pastures, gardens, walks, parks, or cornfields. James Silk Buckingham, for example, described in 1842 a triangular plot of land created by intersecting roads. In James E. Teschemacher’s 1835 report of a garden building, he describes a crescent-shaped plot, which he instructed should be kept closely mown and planted with ornamental trees.

Plots regarded as part of the cultivated, designed landscape could be planted with a variety of vegetation depending on their use. Grass was most commonly used, and a plot most frequently referred to a grassy space located near a house, particularly in the late eighteenth and first half of the nineteenth centuries, when the practice of surrounding a house with lawn became more prevalent (see Lawn). The wide variety of terms to describe the expanse of turf either in front of or behind a house is exemplified by [[Mount Vernon], where the grassy area in front of the house was described variously as plot, plat, lawn, and bowling green (see Bowling green).

Ornamentation of grass plots changed during this same period. Early descriptions of grass plots suggest a broad turfed area, perhaps bordered by ornamental shrubs and trees. Flower beds do not appear in these descriptions and, in fact, in 1803 Elizabeth Drinker recounted removing flowers from the garden in order to convert the space into grass plots with trees. By the 1820s and 1830s, descriptions of grass plots make it clear that they contained flower beds, as well as ornamental trees and shrubs. Marking the boundaries of plots was often a concern and was accomplished through the use of both organic and inorganic materials. In 1629 early English settler John Smith described setting the limits of plots with rows of trees, a technique that provided shade and a wind-break, and thus sheltered the plots’ contents. The grass plot at the Charles Norris House in Philadelphia, as described in 1867, was bordered by “roses intermixed with currant bushes.”[1] William Tennent’s 1764 prospect of Nassau Hall at the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University) depicts a grass plot, in front of the hall, demarcated by a fence [Fig. 2]. Bricks were used to enclose the plots at the State House in Philadelphia, according to William Dickinson Martin (1809). Such boundaries not only protected the space from destruction by animals, but also designated it as a special segment of the ground set apart for ornamental and utilitarian purposes.

Webster also used the term “grass-plat” to define an esplanade in a gardening context. Samuel Deane (1790) described plat as a topographically level partition of a garden. Thomas Green Fessenden (1828) and Joseph Breck (1851) continued this connotation of flatness and used the term to describe the ideal flat setting for a garden. William Cobbett (1819) equated the term with “quarter,” explaining that both terms referred to small subdivisions of a garden (see Quarter). He added that plat was the more universally understood appellation of the feature, whereas quarter was associated with specifically British usage. Plat could also refer to a portion of a map or plan that was subdivided for settlement, or to the actual subdivided lots indicated on the plan.[2] In general, references to subdivisions (or sections of ground) constitute the most common usage of this term [Fig. 3] and are the focus of the most frequently cited examples discussed here.

The grass plat was an essential component of garden design from at least the mid-eighteenth to the mid-nineteenth centuries, and the form could vary in size and shape. At William Byrd III’s Westover on the James River, in 1783, Thomas Lee Shippen described a 300-foot-by-100-yard expanse between the house and the river as a plat, and C. M. Hovey, in 1841, referred to a circular plat 100 feet in diameter at James Dundas’s residence in Philadelphia. The plat of Hermitage, Andrew Jackson’s estate in Nashville, was described as guitar shaped.

Situated adjacent to a residence, a grass plat, like a lawn or grass plot, functioned as a frame or setting [Fig. 4]. Perhaps because of this association with the residence, in particular, plat came to be regarded as analogous to yard (see Yard). An article in the Horticultural Register (1837), for example, castigated the American trend of clearing away all vegetation around the house, leaving an unornamented yard or, slightly better, “a handsome grass plat.” Walter Elder’s 1849 recommendation that a grass plat near a house could be used as a bleaching area for cloth recalls the utilitarian associations of yards.

Grass plats were not always attached to houses. Large stretches of turf, perhaps edged with walks or roads, were also incorporated into public gardens and designed landscapes, as in the representation of Gray’s Garden and Fairmount Waterworks in Philadelphia [Fig. 5]. Grass plats could also be decorated with flowers, statues, or seats and they could be bounded by vegetation, walks, or fences. Plat borders might be less obviously marked, for example, if the landscape gardener or designer utilized a ha-ha (or sunk fence), as recommended by Teschemacher in 1835. Because of the variety of ornamentation that could be accommodated by the plat, the feature bridged different styles of garden design that flourished during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

-- Anne L. Helmreich

Texts

Usage

- Callender, Hannah, 1762, describing Belmont Mansion, estate of Judge William Peters, near Philadelphia, Pa. (quoted in Vaux 1888: 455) [3]

- “On the right you enter a labyrinth of hedge of low cedar and spruce. In the middle stands a statue of Apollo.”

- Cutler, Rev. Manasseh, 14 July 1787, describing Gray’s Tavern, Philadelphia, Pa. (1987: 1:277) [4]

- “Here is a curious labyrinth with numerous windings begun, and extends along the declivity of the hill toward the gardens, but has hardly yet received its form.”

- Constantia [pseud.], 24 June 1790, “Description of Gray’s Gardens, Pennsylvania” (Massachusetts Magazine 3: 414–15)

- “this, as well as all the smaller avenues, alike produces us in the wilderness, into which we enter, passing over a neat chinese bridge, preparing with much pleasure to penetrate a recess so charming. It is indeed a wilderness of sweets, and the views instantly become romantically enchanting, the scene is every moment changing. Now, side long bends the path; then, pursues its winding way; now, in a straight line; then, in a pleasing labyrinth is lost, until, in every possible direction, it breaketh upon us, amid thick groves of pines, walnuts, chestnuts, mulberries, &c. &c. we seem to ramble, while at the same time, we are surprized [sic] by borders of the richest, and most highly cultivated flowers, in the greatest variety, which even from a royal parterre we might be led to expect.”

- Washington, George, 14 October 1792, describing Mount Vernon, plantation of George Washington, Fairfax County, Va. (quoted in Martin 1991: 216 fn. 20) [5]

- Jefferson, Thomas, 1804, describing Monticello, plantation of Thomas Jefferson, Charlottesville, Va. (quoted in Nichols and Griswold 1978: 109) [6] back up to discussion

- “The best way of forming thicket will be to plant it in labyrinth spirally, putting the tallest plants in the center & lowering gradation to the external termination. a temple or seat may be in the center, thus leaving space enough between the rows to walk & to trim up, replant [a three-pronged diagram] the shrubs.” [Fig. 9]

- Jefferson, Thomas, 1808, describing Monticello, plantation of Thomas Jefferson, Charlottesville, Va. (1944: 384) [7]

- “To describe on the ground the Labyrinth of broom.

- “go to the 5th. beginning in the avenue of broom for the apple-tree-rows, viz. a.

- “measure off at right angles with that 165. f. to b.

- “describe round a circle of 55. f radius

- “where it crosses the line a. b. viz. at c. stick a pin.

- “divide the circle into 8. parts, sticking pins, viz at 43.2 f distance measured on the periphery.

- “lay off a tangent from each point (with the theodolite)

- “take the radius (55 f.) on that tangent & describe a quadrant from the pin in the periphery

- “take for a new center the pin in the periphery which is a quadrant distant from the pin last mentd. & with the semicircle (110 f.) for a radius describe from the end of the last quadrant a portion of a circle till it intersects the tangent.

- “on each side of this spiral, parallel to it, & at 9 f. distance from it describe lines.

- “plant broom every 6 f. along these lines, and allowing the plants to put out branches 6. f. each way it will leave walks of 6. f. wide, without ever rendg. necessy to trim.

- “between walk & walk the whole interval must be filled with broom at 6. f. distance. to bound which properly, a circle of 165 f. rad. must be circumscribd round the whole.

- “(note these walks will go off from the circle where the plats of broom were erroneously placed in the figure.)”

- Kellogg, Miner K., c.1825–27, describing a settlement in New Harmony, Ind. (quoted in Pitzer and Elliott 1979: 288) [8]

- “The first Labyrinth I ever saw was at New Harmony. It was grown in an open field near the town and a source of constant amusement to children. Its lines were formed of vines grown upon light fences and about four feet high, converging as they reached the centre. Here the visitor came upon a circular hut made of the ends of rough logs cut to a point externally leaving one window—& a blind door which had to be sought out—& only found by pushing at the walls.” [Fig. 10]

- Kennedy, John Pendleton, 1833, in an address to the Horticultural Society of Maryland, describing the flower hall of the First Annual Exhibition (p. 25) [9]

- “A garden is a theme of pleasant recollections to us in every stage of life. We remember, with a peculiar fondness, those days of infancy which were spent in playing through the labyrinths of the trimmed hedges of box, and where the althea, the lilac and the hawthorn, bounded the parterre.”

Citations

- Lawson, William, 1618, A New Orchard and Garden ([1618] 1982: 11) [10]

- “If within one large square the Gardiner shall make one round Labyrinth or Maze with some kind of beries, it will grace your forme, so there be sufficient roomth left for walks, so will foure or moe round knots doe.”

- Parkinson, John, 1629, Paradisi in Sole Paradisus Terrestris ([1629] 1975: 5) [11]

- “For there may be therein [the garden] walkes eyther open or close, eyther publike or private, a maze or wildernesse.”

- [Dézallier d’Argenville, A.-J.], 1712, The Theory and Practice of Gardening ([1712] 1969: 60) [12]

- "Lastly, The tenth Plate of Groves contains the Design of a Labyrinth, of a Contrivance entirely new: 'Tis a large Volute or Spiral Walk, in the Center of which is a Bason, accompanied with a Hall pierced by weight Walks, which carry you to four Cross-Ways, from whence you pass insensibly into the Windings of the Maze, set off with Cabinets, Latticed-Arbors, Green-plots, Fountains, Figures, &c. which very agreeably surprize and amuse those that have lost their Way in it. The great number of Alleys, and the various Turnings in the Composition of this Labyrinth, render it extremely intricate and puzzling, without taking any thing from the Beauty and Regularity of the Design. There is but one Entrance into it, which is also the Outlet, where there is placed a Cabinet of Lattice-work, on purpose to render it still more difficult." [Fig. 11]

- Langley, Batty, 1728, New Principles of Gardening ([1728] 1982: 195–96) [13]

- “General DIRECTIONS, &c. . . .

- “X. That all those Parts which are out of View from the House, be form’d into Wildernesses, Labyrinths, &c.”

- Chambers, Ephraim, 1741–43, Cyclopaedia (2:n.p.) [14]

- “LABYRINTH . . . among the ancients, was a large intricate edifice cut out into various isles, and meanders, running into each other, so as to render it difficult to get out of it.”

- Johnson, Samuel, 1755, A Dictionary of the English Language (2:n.p.) [15] back up to discussion

- “LA’BYRINTH. n.s. [labyrinthus, Latin.] A maze; a place formed with inextricable windings.”

- Miller, Philip, 1759, The Gardeners Dictionary (n.p.) [16] back up to discussion

- “Labyrinth, a winding, mazy, and intricate turning to and fro, through a Wilderness or Wood. The Design of a labyrinth is to cause an intricate and difficult Labour to find the center, and the Aim is, to make Walks so intricate, that a Person may lose himself in them. . . . As to the Contrivance of them, it will not be possible to give Directions in Words, there are several plans and designs in Books on Gardening; they are rarely met with success but in great & noble gardens, as Hampton, Court.”

- Sheridan, Thomas, 1789, A Complete Dictionary of the English Language (n.p.) [17] back up to discussion

- “LABYRINTH, lab’-ber-inth. s. . . . a place formed with inextricable windings.”

- Anonymous, 1798, Encyclopaedia (7:542) [18] back up to discussion

- “When wildernesses are intended, they should not be cut into stars and other ridiculous figures, nor formed into mazes or labyrinths, which in a great design appear trifling.”

- M’Mahon, Bernard, 1806, The American Gardener’s Calendar (pp. 67–68) [19]

- “A Labyrinth, is a maze or sort of intricate wilderness-plantation, abounding with hedges and walks, formed into many windings and turnings, leading to one common centre, extremely difficult to find out; designed in large pleasure-grounds by way of amusement.

- “It is generally formed with hedges, commonly in double rows, leading in various intricate turnings, backward and forward, with intervening plantations, and gravel-walks alternately between hedge and hedge; the great aim is to have the walk contrived in so many mazy, intricate windings, to and fro, that a person may have much difficulty in finding out the centre, by meeting with as many stops and disappointments as possible; for he must not cross, or break through the hedges; so that in a well contrived labyrinth, a stranger will often entirely loose himself, so as not to find his way to the centre, nor out again.

- “As to plans of them, it is impossible to describe such, by words, any further than the above hints, and their contrivance must principally depend, on the ingenuity of the designer.

- “But as to the hedges, walks, and trees; the hedges are usually made of hornbeam, beech, elm, or any other kind that can be kept neat by clipping. The walks should be five feet wide at least, laid with gravel, neatly rolled, and kept clean; and the trees and shrubs to form a thicket of wood between the hedges, may be of any hardy kinds of the deciduous tribe, interspersed with some evergreens; and in the middle of the labyrinth should be a spacious open, ornamented with some rural seats and shady bowers, &c.

- “Sometimes small labyrinths are formed with box-edgings, and borders for plants, with handsome narrow walks between, in imitation of the larger ones; which have a very pleasing and amusing effect in small gardens.”

- Gregory, G., 1816, A New and Complete Dictionary of Arts and Sciences (2:n.p.) [20]

- “LABYRINTH, in gardening, a winding mazy walk between hedges, through a wood or wilderness. The chief aim is to make the walks so perplexed and intricate, that a person may lose himself in them, and meet with as great a number of disappointments as possible. They are rarely to be meet with, except in great gardens; as Versailles, Hampton-court, &c.”

- Webster, Noah, 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (n.p.) [21] back up to discussion

- “LAB’YRINTH, n. [L. labyrinthus. . . .]

- “1. Among the ancients, an edifice or place full of intricacies, or formed with winding passages, which rendered it difficult to find the way from the interior to the entrance. The most remarkable of these edifices mentioned, are the Egyptian and the Cretan labyrinths. Encyc. Lempriere.

- “2. A maze; an inexplicable difficulty.

- “3. Formerly, an ornamental maze or wilderness in gardens. Spenser.”

- Johnson, George William, 1847, A Dictionary of Modern Gardening (p. 336) [22]

- “LABYRINTH is an arrangement of walks, inclosed by hedges or shrubberies, so intricate as to be very difficult to escape from. From the twelfth century to the end of the seventeenth, they were a very favourite portion of English pleasure grounds, but they are now more judiciously banished.”

- Downing, A. J., 1849, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (p. 91) [23] back up to discussion

- “One of the favorite fancies of the geometric gardener was the Labyrinth . . . of which a few celebrated examples are still in existence in England, and which consisted of a multitude of trees thickly planted in impervious hedges, covering sometimes several acres of ground. These labyrinths were the source of much amusement to the family and guests, the trial of skill being to find the centre, and from that point to return again without assistance; and we are told by a historian of the garden of that period, that ‘the stranger having once entered, was sorely puzzled to get out.’” [Fig. 12]

Images

Inscribed

Michael van derGucht, “The Design of a Labyrinth with Cabinets and Fountains”, in [A.-J. Dézallier d’Argenville], The Theory and Practice of Gardening (1712), pl. 10.

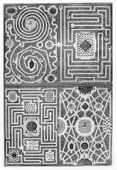

Batty Langley, "Several Designs for Wildernesses and Labyrinths," in New Principles of Gardening (1728), pl. VII.

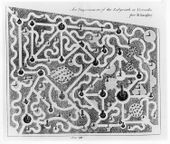

Batty Langley, “An Improvement of the Labyrinth at Versailles,” in New Principles of Gardening (1728), pl. VIII.

Thomas Jefferson, Letter describing plans fora “Garden Olitory” at Monticello [detail], c. 1804.

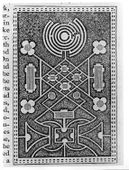

J. C. Loudon, Plan of a pleasure-ground with labyrinth, in An Encyclopaedia of Gardening (1826), p. 1021, fig. 719.

Charles Varlé, “Project for the improvement of the Square and the Town of Bath," 1809.

Hugh Bridport, The Pagoda and Labyrinth Garden, c. 1828.

Anonymous, “A Labyrinth,” in A. J. Downing, A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1849), p. 91, fig. 17.

Associated

Attributed

Batty Langley, “An Improvement of a beautiful Garden at Twickenham,", in New Principles of Gardening (1728), pl. IX.

W. Weingartner, Town Plan of Harmonie, Indiana, 1833.

Benjamin Franklin Smith, Jr. (artist), William Wellstood (engraver), "From the Latting Observatory," 1855.

Notes

- ↑ Deborah Logan, The Norris House (Philadelphia: The Fair-Hill Press, 1867), 8. view on Zotero

- ↑ For = the use of this term in the context of American settlement patterns, see Hildegard Binder Johnson, “Towards a National Landscape,” in The Making of the American Landscape, ed. Michael P. Conzen (New York: Routledge, 1990), 127–45. view on Zotero

- ↑ Vaux, George. 1888. “Extracts from the Diary of Hannah Callender.” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 12 (1): 432–56. view on Zotero

- ↑ Cutler, Manasseh. 1987. Life, Journals, and Correspondence of Rev. Manasseh Cutler. Edited by William Parker Cutler and Julia Perkin Cutler. 2 vols. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press. view on Zotero

- ↑ Martin, Peter. 1991. The Pleasure Gardens of Virginia: From Jamestown to Jefferson. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. view on Zotero

- ↑ Nichols, Frederick Doveton, and Ralph E. Griswold. 1978. Thomas Jefferson, Landscape Architect. Charlottesville, Va.: University Press of Virginia. view on Zotero

- ↑ Jefferson, Thomas. 1944. The Garden Book. Edited by Edwin M. Betts. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society. view on Zotero

- ↑ Pitzer, Donald E., and Josephine Elliott. 1979. “New Harmony’s First Utopias, 1814-1824.” Indiana Magazine of History 75 ((September)): 225–300. view on Zotero

- ↑ Kennedy, John Pendleton. 1833. Address Delivered before the Horticultural Society of Maryland at Its First Annual Exhibition, June 12, 1833. Baltimore, Md.: John D. Toy. view on Zotero

- ↑ Lawson, William. [1618] 1982. A New Orchard and Garden... with the Country Housewifes Garden. New York: Garland. view on Zotero

- ↑ Parkinson, John. 1629. Paradisi in Sole Paradisus Terrestris. London: Humfrey Lownes and Robert Young. view on Zotero

- ↑ [Dézallier d'Argenville, A.-J. (Antoine Joseph)]. [1712] 1969. The Theory and Practice of Gardening; wherein is fully handled all that relates to fine gardens, . . . containing divers plans, and general dispositions of gardens; . . . English-language edition prepared by John James from the 1709 French original and printed in London by Geo. James. Reprint, Farnborough, England: Gregg. view on Zotero

- ↑ Langley, Batty. [1728] 1982. 'New Principles of Gardening, or The Laying out and Planting Parterres, Groves, Wildernesses, Labyrinths, Avenues, Parks, &c. Originally published London: A. Bettesworth and J. Batley, etc. view on Zotero

- ↑ Chambers, Ephraim. 1741-1743. Cyclopaedia, or An Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences. . . . 2 vols. London: D. Midwinter et al. view on Zotero

- ↑ Johnson, Samuel. 1755. A Dictionary of the English Language: In Which the Words Are Deduced from the Originals and Illustrated in the Different Significations by Examples from the Best Writers. 2 vols. London: W. Strahan for J. and P. Knapton. view on Zotero

- ↑ Miller, Philip. 1759. The Gardeners Dictionary: Containing the Methods of Cultivation and Improving the Kitchen, Fruit, and Flower Garden. As Also, the Physick Garden, Wilderness, Conservatory, and Vineyard... Interspers’d with the History of the Plants, the Characters of Each Genus and the Names of All the Particular Species, in Latin and English; and an Explanation of All the Terms Used in Botany and Gardening, Etc. 7th ed. London: Philip Miller. view on Zotero

- ↑ Sheridan, Thomas A. 1789. A Complete Dictionary of the English Language, Carefully Revised and Corrected by John Andrews.... 5th ed. Philadelphia: William Young. view on Zotero

- ↑ 1798. Encyclopaedia, or A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and Miscellaneous Literature. 18 vols. Philadelphia: Thomas Dobson. view on Zotero

- ↑ M’Mahon, Bernard. 1806. The American Gardener’s Calendar: Adapted to the Climates and Seasons of the United States. Containing a Complete Account of All the Work Necessary to Be Done... for Every Month of the Year.... Philadelphia: Printed by B. Graves for the author. view on Zotero

- ↑ Gregory, G. 1816. A New and Complete Dictionary of Arts and Sciences. 3 vols. Philadelphia: Isaac Peirce. view on Zotero

- ↑ Webster, Noah. 1828. An American Dictionary of the English Language. 2 vols. New York: S. Converse. view on Zotero

- ↑ Johnson, George William. 1847. A Dictionary of Modern Gardening. Edited by David Landreth. Philadelphia: Lea and Blanchard. view on Zotero

- ↑ Downing, A. J. [Andrew Jackson]. 1849. A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted to North America; with a View to the Improvement of Country Residences. Comprising Historical Notices and General Principles of the Art, Directions for Laying out Grounds and Arranging Plantations, the Description and Cultivation of Hardy Trees, Decorative Accompaniments to the House and Grounds, the Formation of Pieces of Artificial Water, Flower Gardens, Etc.: With Remarks on Rural Architecture. 4th ed. New York: G. P. Putnam. view on Zotero