Labyrinth

See also: Walk, Wilderness

Discussion

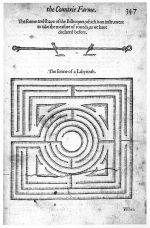

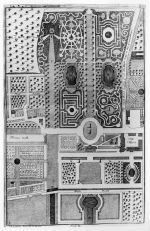

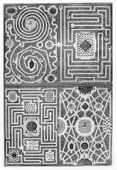

Although labyrinth was the term of choice for professional writers such as Thomas Sheridan (1789), who described it as “a place formed with inextricable windings,” the term was virtually synonymous with that of “maze” in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century gardening literature, as well as in general usage.[1] Samuel Johnson, for example, in 1755 defined labyrinth as “a maze.” The winding walks referred to by Johnson and other garden writers (such as Philip Miller and Bernard M’Mahon) were the distinguishing feature of labyrinths. This characteristic was also clear in illustrations from English garden treatises that were available in North America [Figs. 1–3]. These sharply turning walkways were frequently framed by dense, high hedges, and often backed by shrubs and woods that occluded the perambulator’s view (see Walk). A visitor’s perception was affected by the combination of dense vegetation and intricately patterned walks, which produced an intentional state of disorientation and surprise. If the visitor succeeded in penetrating to the center of the labyrinth, he or she was typically rewarded by arriving at an ornamented space, often highlighted with a garden structure, such as an obelisk, a temple, or a seat. Thomas Jefferson (1804) suggested such a design in his reference to a thicket labyrinth.

Gardeners and garden writers of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries mentioned a broad range of vegetation that could be used to construct this garden feature. Hannah Callender (1762) referred to cedar and spruce that were maintained as a hedge (view citation); George Washington mentioned pine; Jefferson specified broom; and John Pendleton Kennedy reminisced about boxwood. M’Mahon recommended hedges of hornbeam (a nut-bearing tree), beech, elm, “or any other kind that can be kept neat by clipping,” or, in the case of smaller labyrinths, box edged with plants. All of these materials could produce the desired density and could also, because of either thickness or prickly texture, prevent visitors from wandering off the carefully laid out paths. Because these plants also tolerated trimming well, the edges of walks could be cleanly demarcated. At times, nonliving material was substituted for living hedges and borders. At New Harmony, for example, four-foot-high wooden fences covered with various climbing vines were used to define the walks.

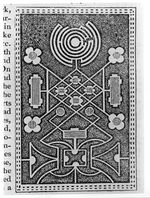

Many of the plants utilized in labyrinths were also employed in wildernesses, as was the technique of planting low hedges or borders backed by trees and shrubs (see Wilderness). Hence, many garden writers conflated labyrinth and wilderness, as in the case of John Parkinson (1629). The labyrinth at times was referred to as a specialized form of wilderness, for example M’Mahon(1806). Although Batty Langley, in New Principles of Gardening (1728), referred to wildernesses and labyrinths as separate features, he treated them similarly, placing them in remote regions of gardens and even balancing one against another, as in the plan for an improved garden at Twickenham. His description of this garden specified the location of the labyrinth, among the grove and wilderness, seen above the statue in the plan [Fig. 4]. He described the “Improvement of the Labyrinth at Versailles” [Fig. 5] as “the finest design of any” that he had ever seen.

While the meaning of the term “labyrinth” was relatively clear throughout the period of this study, the history of its presence in American gardens is less well understood. According to Philip Miller (1759), labyrinths were a rarity in English gardens and successful only in large-scale gardens, such as those at Hampton Court. Given these conditions, one might expect few labyrinths in the American context, especially since the funds and royal imperative associated with Hampton Court were largely absent in the New World.[2]

Nevertheless, a number of labyrinths in public and private American grounds have been documented. Labyrinths were sources of amusement and therefore were included in the popular public gardens, such as Gray’s Tavern in Philadelphia, and Berkeley Springs in Virginia (later West Virginia) [Fig. 6]. In 1762 Hannah Callender described a labyrinth at Judge William Peters’s Belmont Mansion, near Philadelphia. In this garden, the labyrinth was part of a larger arrangement of features, including parterres, topiary, and clipped hedges, which were associated with the geometric or ancient style as opposed to modern fashion (see Ancient style, Geometric style, and Modern style).[3] Labyrinths were built at Mount Vernon and Monticello. Jefferson made a labyrinth in the thicket, a garden feature closely related to shrubbery and often associated with the modern or natural style of landscape gardening (see Modern style and Thicket).

Most descriptions of labyrinths in the American context unfortunately do not specify labyrinth design, which could take on a variety of configurations. The condemnation of “stars and other ridiculous figures” issued by the Encyclopaedia (1798) suggests some range of taste or preference in the areas of design. Jefferson’s plan of Monticello is exceptional because it documents a spiral, pinwheel-like arrangement of shrubs, with six-foot-wide walks evenly dispersed. The plan of the labyrinth at Harmony, Pa., is an elaborate version of a spiral configuration [Fig. 7] and was repeated at the settlement in New Harmony, Ind., which was modeled after the Pennsylvania community.

The evidence of labyrinths in early American gardens suggests that the number of labyrinths declined as the feature was increasingly associated with old-fashioned garden practices. In his dictionary (1828), Noah Webster stated that the garden oriented definition of labyrinth was no longer used. A. J. Downing, in his 1849 edition of A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, firmly categorized labyrinths under the rubric of the geometric (or ancient) garden style of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Yet, labyrinths never completely disappeared from the American landscape, as demonstrated by a view from the Mount Croton Garden in New York [Fig. 8], and its elaborate hedged labyrinth, exactly in the rectangular form that Downing declared was used by ancient gardeners. The popularity of this labyrinth for public amusement assured its continuity.

-- Anne L. Helmreich

Texts

Usage

- Callender, Hannah, 1762, describing Belmont Mansion, estate of Judge William Peters, near Philadelphia, Pa. (quoted in Vaux 1888: 455) [4] back up to discussion

- “On the right you enter a labyrinth of hedge of low cedar and spruce. In the middle stands a statue of Apollo.”

- Cutler, Rev. Manasseh, 14 July 1787, describing Gray’s Tavern, Philadelphia, Pa. (1987: 1:277) [5]

- “Here is a curious labyrinth with numerous windings begun, and extends along the declivity of the hill toward the gardens, but has hardly yet received its form.”

- Constantia [pseud.], 24 June 1790, “Description of Gray’s Gardens, Pennsylvania” (Massachusetts Magazine 3: 414–15)

- “this, as well as all the smaller avenues, alike produces us in the wilderness, into which we enter, passing over a neat chinese bridge, preparing with much pleasure to penetrate a recess so charming. It is indeed a wilderness of sweets, and the views instantly become romantically enchanting, the scene is every moment changing. Now, side long bends the path; then, pursues its winding way; now, in a straight line; then, in a pleasing labyrinth is lost, until, in every possible direction, it breaketh upon us, amid thick groves of pines, walnuts, chestnuts, mulberries, &c. &c. we seem to ramble, while at the same time, we are surprized [sic] by borders of the richest, and most highly cultivated flowers, in the greatest variety, which even from a royal parterre we might be led to expect.”

- Washington, George, 14 October 1792, describing Mount Vernon, plantation of George Washington, Fairfax County, Va. (quoted in Martin 1991: 216 fn. 20) [6]

- Jefferson, Thomas, 1804, describing Monticello, plantation of Thomas Jefferson, Charlottesville, Va. (quoted in Nichols and Griswold 1978: 109) [7]

- “The best way of forming thicket will be to plant it in labyrinth spirally, putting the tallest plants in the center & lowering gradation to the external termination. a temple or seat may be in the center, thus leaving space enough between the rows to walk & to trim up, replant [a three-pronged diagram] the shrubs.” [Fig. 9]

- Jefferson, Thomas, 1808, describing Monticello, plantation of Thomas Jefferson, Charlottesville, Va. (1944: 384) [8]

- “To describe on the ground the Labyrinth of broom.

- “go to the 5th. beginning in the avenue of broom for the apple-tree-rows, viz. a.

- “measure off at right angles with that 165. f. to b.

- “describe round a circle of 55. f radius

- “where it crosses the line a. b. viz. at c. stick a pin.

- “divide the circle into 8. parts, sticking pins, viz at 43.2 f distance measured on the periphery.

- “lay off a tangent from each point (with the theodolite)

- “take the radius (55 f.) on that tangent & describe a quadrant from the pin in the periphery

- “take for a new center the pin in the periphery which is a quadrant distant from the pin last mentd. & with the semicircle (110 f.) for a radius describe from the end of the last quadrant a portion of a circle till it intersects the tangent.

- “on each side of this spiral, parallel to it, & at 9 f. distance from it describe lines.

- “plant broom every 6 f. along these lines, and allowing the plants to put out branches 6. f. each way it will leave walks of 6. f. wide, without ever rendg. necessy to trim.

- “between walk & walk the whole interval must be filled with broom at 6. f. distance. to bound which properly, a circle of 165 f. rad. must be circumscribd round the whole.

- “(note these walks will go off from the circle where the plats of broom were erroneously placed in the figure.)”

- Kellogg, Miner K., c.1825–27, describing a settlement in New Harmony, Ind. (quoted in Pitzer and Elliott 1979: 288) [9]

- “The first Labyrinth I ever saw was at New Harmony. It was grown in an open field near the town and a source of constant amusement to children. Its lines were formed of vines grown upon light fences and about four feet high, converging as they reached the centre. Here the visitor came upon a circular hut made of the ends of rough logs cut to a point externally leaving one window—& a blind door which had to be sought out—& only found by pushing at the walls.” [Fig. 10]

- Kennedy, John Pendleton, 1833, in an address to the Horticultural Society of Maryland, describing the flower hall of the First Annual Exhibition (p. 25) [10]

- “A garden is a theme of pleasant recollections to us in every stage of life. We remember, with a peculiar fondness, those days of infancy which were spent in playing through the labyrinths of the trimmed hedges of box, and where the althea, the lilac and the hawthorn, bounded the parterre.”

Citations

- Lawson, William, 1618, A New Orchard and Garden ([1618] 1982: 11) [11]

- “If within one large square the Gardiner shall make one round Labyrinth or Maze with some kind of beries, it will grace your forme, so there be sufficient roomth left for walks, so will foure or moe round knots doe.”

- Parkinson, John, 1629, Paradisi in Sole Paradisus Terrestris ([1629] 1975: 5) [12]

- “For there may be therein [the garden] walkes eyther open or close, eyther publike or private, a maze or wildernesse.”

- Langley, Batty, 1728, New Principles of Gardening ([1728] 1982: 195–96) [13]

- “General DIRECTIONS, &c. . . .

- “X. That all those Parts which are out of View from the House, be form’d into Wildernesses, Labyrinths, &c.”

- Chambers, Ephraim, 1741–43, Cyclopaedia (2:n.p.) [14]

- “LABYRINTH . . . among the ancients, was a large intricate edifice cut out into various isles, and meanders, running into each other, so as to render it difficult to get out of it.”

- Johnson, Samuel, 1755, A Dictionary of the English Language (2:n.p.) [15]

- “LA’BYRINTH. n.s. [labyrinthus, Latin.] A maze; a place formed with inextricable windings.”

Images

Inscribed

John Haviland, The Pagoda and Labyrinth Garden, Fairmount Waterworks, c. 1828. The Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pa.

Batty Langley, "Four several Designs for Wildernesses and Labyrinths", 1728.

Associated

Attributed

W. Weingartner, Town Plan of Harmonie, Indiana, 1833. Pennsylvania State Archives.

W. Weingartner, Town Plan of Harmonie, Indiana, 1833. Pennsylvania State Archives, detail.

Notes

- ↑ For a general discussion of labyrinths in gardens, with illustrated examples, see Adrian Fisher and George Gester, Labyrinth, Solving the Riddle of Maze (New York: Harmony Books, 1990).

- ↑ It should be noted that the maze currently located in the grounds of the Governor’s Palace, Williamsburg, Va., is a twentieth-century construction for which no documentation during the colonial period of habitation exists. See Charles B. Hosmer, “The Colonial Revival in the Public Eye: Williamsburg and Early Garden Restoration,” in The Colonial Revival in America, ed. Alan Axelrod (New York: W. W. Norton, 1985) for a discussion of the Williamsburg gardens and their role in defining colonial revival garden styles.

- ↑ Therese O’Malley, “Landscape Gardening in the Early National Period,” in Views and Visions, American Landscape before 1830, ed. Edward J. Nygren with Bruce Robertson(Washington, D.C.: Corcoran Gallery of Art, 1986), 144.

- ↑ Vaux, George. 1888. “Extracts from the Diary of Hannah Callender.” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 12 (1): 432–56. view on Zotero

- ↑ Cutler, Manasseh. 1987. Life, Journals, and Correspondence of Rev. Manasseh Cutler. Edited by William Parker Cutler and Julia Perkin Cutler. 2 vols. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press. view on Zotero

- ↑ Martin, Peter. 1991. The Pleasure Gardens of Virginia: From Jamestown to Jefferson. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. view on Zotero

- ↑ Nichols, Frederick Doveton, and Ralph E. Griswold. 1978. Thomas Jefferson, Landscape Architect. Charlottesville, Va.: University Press of Virginia. view on Zotero

- ↑ Jefferson, Thomas. 1944. The Garden Book. Edited by Edwin M. Betts. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society. view on Zotero

- ↑ Pitzer, Donald E., and Josephine Elliott. 1979. “New Harmony’s First Utopias, 1814-1824.” Indiana Magazine of History 75 ((September)): 225–300. view on Zotero

- ↑ Kennedy, John Pendleton. 1833. Address Delivered before the Horticultural Society of Maryland at Its First Annual Exhibition, June 12, 1833. Baltimore, Md.: John D. Toy. view on Zotero

- ↑ Lawson, William. [1618] 1982. A New Orchard and Garden... with the Country Housewifes Garden. New York: Garland. view on Zotero

- ↑ Parkinson, John. 1629. Paradisi in Sole Paradisus Terrestris. London: Humfrey Lownes and Robert Young. view on Zotero

- ↑ Langley, Batty. [1728] 1982. 'New Principles of Gardening, or The Laying out and Planting Parterres, Groves, Wildernesses, Labyrinths, Avenues, Parks, &c. Originally published London: A. Bettesworth and J. Batley, etc. view on Zotero

- ↑ Chambers, Ephraim. 1741-1743. Cyclopaedia, or An Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences. . . . 2 vols. London: D. Midwinter et al. view on Zotero

- ↑ Johnson, Samuel. 1755. A Dictionary of the English Language: In Which the Words Are Deduced from the Originals and Illustrated in the Different Significations by Examples from the Best Writers. 2 vols. London: W. Strahan for J. and P. Knapton. view on Zotero