Difference between revisions of "Grove"

V-Federici (talk | contribs) m (→Inscribed) |

|||

| (126 intermediate revisions by 11 users not shown) | |||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

==History== | ==History== | ||

| − | The term grove referred to both natural and planted arrangements of trees, as indicated by Noah | + | [[File:0605.jpg|thumb|left|550 px|Fig. 1, Lieut. Birch, ''Plan of St. Augustine, Fla.'', 1819.]] |

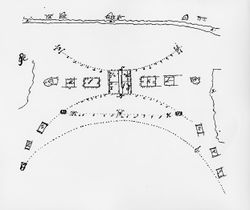

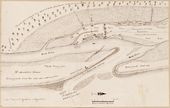

| + | The term grove referred to both natural and planted arrangements of trees, as indicated by [[Noah Webster]]’s definition of 1828. American gardeners such as [[Bernard M’Mahon]] (1806) realized the potential of indigenous vegetation and simply thinned existing trees to create so-called “natural” groves. Trees could also be planted where none existed to create “artificial” groves. Whether natural or artificial, groves of trees were an important element in the ornamental landscape, serving aesthetic and agricultural purposes. As Samuel Deane explained in the ''New-England Farmer'' (1790), groves could provide shade and windbreaks as well as syrup, firewood, and fruit. As a formal element, groves defined [[border]]s of gardens, created backdrops, and, as seen in the sketch of St. Augustine’s orange grove [Fig. 1], offered sites for collecting specific plants. | ||

| − | While generally composed of trees, groves sometimes included | + | While generally composed of trees, groves sometimes included [[shrub]]s and flowers. These plants were also found in [[wood]]s, [[shrubberies]], and [[wilderness]]es, thus blurring the lines of distinctions between these features—several treatise writers and lexicographers defined groves, for example, as small [[wood]]s. The overlapping and indistinct uses of the terms “grove,” “[[wilderness]],” and “[[shrubbery]]” are exemplified by George Washington’s notations on the garden at [[Mount Vernon]]. In 1782, he wrote that he would immediately plant groups of “[[shrub]]s and ornamental trees,” and decide later which constituted “the grove and which the [[wilderness]],” implying that the grove would ultimately be the less thickly planted of the two. To add to the confusion, Washington on another occasion referred to the arrangement of trees and [[shrub]]s just south of his house as both a grove and a [[shrubbery]]. Texts from the 19th century mentioned [[shrub]]s and flowers in groves less frequently, because these types of plants were increasingly associated with [[shrubberies]]. Thus, as time passed, the distinction between the terms became more clearly drawn. |

| − | Washington’s notations on the garden at Mount Vernon. In 1782, he wrote that he would immediately plant groups of | ||

| − | When attempting to distinguish groves from other features that employed trees (particularly | + | When attempting to distinguish groves from other features that employed trees (particularly [[wood]]s and [[clump]]s), treatise writers often focused on the question of whether groves should contain undergrowth. Various opinions emerged. Batty Langley argued in ''New Principles of Gardening'' (1728) for the inclusion of flowering [[shrub]]s with evergreens and deciduous trees. Thomas Whately, however, in ''Observations of Modern Gardening'' (1770), believed that a grove consisted of trees without undergrowth in contrast to [[wood]]s or [[clump]]s, which did contain undergrowth. Philip Miller, in ''The Gardeners Dictionary'' (1754), considered undergrowth as one factor that distinguished a “closed” grove from an “open” one. The “open” form of the feature was made by planting large trees at a distance that permitted tree tops to knit together to create a shady canopy for the [[walk]]s below. The “closed” type was composed of a denser planting of trees, [[shrub]]s, and flowers that could be arranged in figures cut through and circumscribed by [[walk]]s. |

| − | + | [[File:0969.jpg|thumb|left|Fig. 2, [[Thomas Jefferson]], Plan of the grounds at [[Monticello]], 1806.]] | |

| + | [[File:2282.jpg|thumb|Fig. 3, [[Pierre Pharoux]], Plan of Esperanza, NY [detail], n.d. A “Public Grove” is situated on either side of the “[[Common]] Ground.”]] | ||

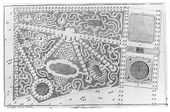

| − | + | The appellations “open” and “closed,” however, were not common in American discourse, despite [[Noah Webster|Noah Webster's]] inclusion of such distinctions in his definition. Although these adjectives were not employed to a significant degree, groves fitting these characteristics can be identified. [[Thomas Jefferson]], in his 1807 account of [[Monticello]], described his intention to trim the lower limbs of the trees in his grove, composed of a mixture of hardwoods and evergreens, “so as to give the appearance of open ground,” suggesting an “open” grove [Fig. 2]. [[Eliza Lucas Pinckney]], in 1742, evoked the sense of a “closed” grove when she delineated her collection of trees and flowers. Likewise, in 1776 George Washington suggested a similar type of grove for [[Mount Vernon]], which he described as an arrangement of flowering trees and evergreens underplanted with flowering [[shrub]]s. | |

| − | In | + | [[File:2255.jpg|thumb|left|Fig. 4, [[Pierre Pharoux]], “General Map of the honorable Wm. frederic Baron of Steuben’s Mannor”, c. 1793.]] |

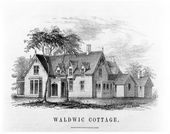

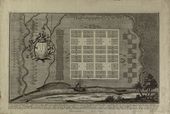

| + | Washington’s account of this “closed” grove also provides a significant clue as to the arrangement of plants. In his 1776 letter to Lund Washington, he specified that the trees “be Planted without any order or regularity,” an aesthetic in keeping with the recommendations of Langley, whose treatises were owned by Washington. The texts of Langley and Miller exemplify the gradual shift away from formal or rectilinear arrangements of trees toward more irregular or “[[natural style|natural]]” designs. 17th-century groves might be planted in [[Geometric_style|geometrical]], or otherwise such patterned figures as “the star, the direct Cross, St. Andrew’s Cross,” described by A.-J. Dézallier d’Argenville (1712). By contrast, |Langley insisted that groves be planted with “regular Irregularity; not planting them. . . with their Trees in straight Lines ranging every Way, but in a rural Manner, as if they had receiv’d their Situation from Nature itself.” In contrast to authors of earlier treatises, 19th-century American writers, including Samuel Deane (1790), [[Bernard M’Mahon]] (1806) and the anonymous author of the ''New England Farmer'' (1828), advocated regular arrangements. Few if any signs, however, indicate that Americans made “closed” groves in [[Geometric_style|geometrical]] figures, such as those described in James. [[Pierre Pharoux]]’s unexecuted plans for the new town Esperanza, New York [Fig. 3], and for Baron von Steuben’s estate in Mohawk Valley, New York [Fig. 4], are rare exceptions. | ||

| − | + | [[File:0730.jpg|thumb|Fig. 5, William Russell Birch, “The Grove in Springland,” before 1805.]] | |

| − | + | In either the regular or irregular arrangement, groves were often designed to accommodate garden structures or decorative elements. William Bentley (1791), for example, called attention to the [[pond]] with [[Statue|statuary]] found in the midst of the grove at Pleasant Hill, Joseph Barrell’s estate in Charlestown, Massachusetts; Margaret Bayard Smith (1809) recorded that [[Thomas Jefferson|Jefferson]] intended to place a monument to a friend in the midst of a grove at [[Monticello]]. William Russell Birch situated a Gothic chapel in the grove at Springland [Fig. 5]. | |

| − | + | In addition to providing settings for decorative objects, groves sometimes displayed rare or unusual tree specimens. At [[Mount Vernon]], Washington contrasted his northern grove, to be made up entirely of locust trees, with his southern grove, to be planted with “clever,” “curious,” and “ornamental” trees and [[shrub]]s. At [[The Woodlands]], [[William Hamilton]] also filled his groves with rare ornamental trees. | |

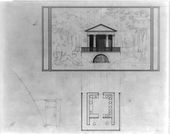

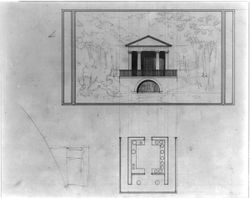

| − | + | [[File:0059.jpg|thumb|left|Fig. 6, [[Benjamin Henry Latrobe]], Spring house—elevation and plan, from “Buildings Erected or Proposed to be Built in Virginia,” 1795–99.]] | |

| + | [[File:0134.jpg|thumb|Fig. 7, Christian Remick, ''A Prospective [[View]] of part of the [[Common]]s'', c. 1768.]] | ||

| + | Groves provided shade and settings for [[walk]]s that linked buildings in a unified composition. They sheltered or highlighted important architectural features. Groves of evergreens or shade trees were well suited for graves and church settings because of the associations with perpetual life. [[Eliza Lucas Pinckney|Pinckney]] and [[Charles Willson Peale]] both spoke of the aura of solemnity found in the deep shade and quiet of their respective groves. Alexander Hamilton (1744) called the “darkened and shaded” grove very “romantick.” Architect [[Benjamin Henry Latrobe]] depicted a [[temple]] deep in a grove, a scene that recalled idealized landscapes associated with the classical past [Fig. 6]. Funerary associations of the grove, dating back to antiquity, made the feature an especially appropriate setting for commemorative monuments and landscape [[cemeteries]]. | ||

| − | + | Groves also connoted cultivation and improvement. They were frequently featured in images, such as Christian Remick’s ''Prospective View of part of the Commons'' (1768) [Fig. 7]. In [[Timothy Dwight]]’s descriptions of the cultivated American landscape, for example, he repeatedly called attention to groves as marking the transition from the wilder or unplanned landscape to the “improved” or worked landscape. Even [[A. J. Downing]], who avoided the term in his treatise, found it useful in describing his ideal [[park]] for the city of New York in 1851. | |

| − | + | —''Anne L. Helmreich'' | |

| − | + | <hr> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Texts== | |

| − | + | ===Usage=== | |

| − | + | *Smith, John, 1612, describing Native American life in America (quoted in Billings 1975: 215)<ref>Warren M. Billings, ed., ''The Old Dominion in the Seventeenth Century: A Documentary History of Virginia, 1606–1689'' (Williamsburg, VA: Institute of Early American History and Culture at Williamsburg, Virginia, 1975), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/S2TZJIN9 view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | of | ||

| − | + | :“Some times from 2 to 100 of these houses [are] togither [''sic''], or but a little separated by '''groves''' of trees. Neare their habitations is [a] little small [[wood]], or old trees on the ground, by reason of their burning of them for fire.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *[[Pinckney, Eliza Lucas]], 1742, describing Wappoo Plantation, property of [[Eliza Lucas Pinckney]], Charleston, SC (1972: 36)<ref>Eliza Lucas Pinckney, ''The Letterbook of Eliza Lucas Pinckney, 1739–1762'', ed. Elise Pinckney (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1972), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/EBQQ2RAU view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | :“You may wonder how I could in this gay season think of planting a Cedar '''grove''', which rather reflects an Autumnal gloom and solemnity than the freshness and gayty of spring. But so it is. I have begun it last week and intend to make it an Emblem not of a lady, but of a compliment which your good Aunt was pleased to make to the person her partiality has made happy by giving her a place in her esteem and friendship. I intend then to connect in my '''grove''' the solemnity (not the solidity) of summer or autumn with the cheerfulness and pleasures of spring, for it shall be filled with all kind of flowers, as well wild as Garden flowers, with seats of Camomoil and here and there a fruit tree—oranges, nectrons, Plumbs, &c., &c.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Norris, Isaac, 22 June 1743, describing Fairhill, seat of Isaac Norris, near Philadelphia, PA (Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Norris Letter Book, 1719–56) | |

| − | + | :“. . . opening my [[wood]]s into '''groves''', enlarging my fishponds and beautifying my springs.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Moore, Francis, 1744, describing the [[Trustees’ Garden]], Savannah, GA (quoted in Marye 1933: 15)<ref>Florence (Nisbet) Marye and Philip Thornton Marye, ''Garden History of Georgia, 1733–1933'', ed. Hattie C. Rainwater and Loraine M. Cooney (Atlanta: Peachtree Garden Club, 1933), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/GNC4U42D view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“On the North-part of the Garden is left standing a '''Grove''' of Part of the old [[Wood]] as it was before the arrival of the Colony there. The Trees in the '''Grove''' are mostly Bay, Sassafras, Evergreen Oak, Pellitory, Hickary [''sic''], American Ash, and the Laurel Tulip.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Hamilton, Alexander, July 14, 1744, describing a house in Rhode Island (1948: 98)<ref>Alexander Hamilton, ''Gentleman’s Progress: The Itinerarium of Dr. Alexander Hamilton, 1744'', ed. Carl Bridenbaugh (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1948), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/EWWJNEUN view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“. . . we passed by an old fashioned wooden house att the end of a lane, darkened and shaded over with a thick '''grove''' of tall trees. This appeared to me very romantick and brought into my mind some romantick descriptions of rural scenes in Spencer’s Fairy Queen.” | |

| − | of | ||

| − | the | ||

| − | |||

| − | East Corner to Colo. Fairfax’s, extending as low as | + | *Washington, George, August 19, 1776, in a letter to Lund Washington, describing [[Mount Vernon]], [[plantation]] of George Washington, Fairfax County, VA (quoted in Riley 1989: 7)<ref>John P. Riley, ''The Icehouses and Their Operations at Mount Vernon'' (Mount Vernon, VA: Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association, 1989), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/76PVTIZM view on Zotero].</ref> |

| − | another line from the Stable to the dry Well, and | + | :“Plant Trees in the room of all dead ones in proper time this Fall. and as I mean to have '''groves''' of Trees at each end of the dwelling House, that at the South end to range in a line from the South East Corner to Colo. Fairfax’s, extending as low as another line from the Stable to the dry Well, and towards the Coach House . . . from the No. Et. Corner of the other end of the House to range so as to show the Barn &ca. in the Neck. . . these Trees to be Planted without any order or regularity (but pretty thick, as they can at any time be thin’d) and to consist that at the North end, of locusts altogether. and that at the South, of all the clever kind of Trees (especially flowering ones) that can be got, such as Crab apple, Poplar, Dogwood, Sasafras, Laurel, Willow (especially yellow and Weeping Willow, twigs of which may be got from Philadelphia) and many others which I do not recollect at present; those to be interspersed here and there with ever greens such as Holly, Pine, and Cedar, also Ivy; to these may be added the Wild flowering [[Shrub]]s of the larger kind, such as the fringe Trees and several other kinds that might be mentioned.” |

| − | towards the Coach House . . . from the No. Et. | ||

| − | Corner of the other end of the House to range so | ||

| − | as to show the Barn &ca. in the Neck . . . these | ||

| − | Trees to be Planted without any order or regularity | ||

| − | (but pretty thick, as they can at any time be | ||

| − | thin’d) and to consist that at the North end, of | ||

| − | locusts altogether. and that at the South, of all the | ||

| − | clever kind of Trees (especially flowering ones) | ||

| − | that can be got, such as Crab apple, Poplar, Dogwood, | ||

| − | Sasafras, Laurel, Willow (especially yellow | ||

| − | and Weeping Willow, twigs of which may be got | ||

| − | from Philadelphia) and many others which I do | ||

| − | not recollect at present; those to be interspersed | ||

| − | here and there with ever greens such as Holly, | ||

| − | Pine, and Cedar, also Ivy; to these may be added | ||

| − | the Wild flowering | ||

| − | as the fringe Trees and several other kinds that | ||

| − | might be mentioned.” | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | “The ground contiguous to this shed was cut | + | *Rush, Dr. Benjamin, July 15, 1782, describing the country [[seat]] of John Dickinsen, near Philadelphia, PA (quoted in Caemmerer 1950: 87)<ref>H. Paul Caemmerer, ''The Life of Pierre-Charles L’Enfant, Planner of the City Beautiful, The City of Washington'' (Washington, DC: National Republic Publishing Company, 1950), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/PHWTAERT view on Zotero].</ref> |

| − | into beautiful | + | :“The ground contiguous to this shed was cut into beautiful [[walk]]s and divided with cedar and pine branches into artificial '''groves'''. The whole, both the buildings and [[walk]]s, were accommodated with [[seat]]s.” |

| − | pine branches into artificial groves. The whole, | ||

| − | both the buildings and | ||

| − | with | ||

| − | |||

| − | describing Mount Vernon, plantation of George | + | *Washington, George, December 25, 1782, describing [[Mount Vernon]], [[plantation]] of George Washington, Fairfax County, VA (quoted in Johnson 1953: 87–88)<ref>Gerald W. Johnson, ''Mount Vernon: The Story of a Shrine'' (New York: Random House, 1953), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/F2JS5DHZ view on Zotero].</ref> |

| − | Washington, Fairfax County, | + | :“I wish that the afore-mentioned [[shrub]]s and ornamental and curious trees may be planted at both ends that I may determine hereafter from circumstances and appearances which shall be the '''grove''' and which the [[wilderness]]. It is easy to extirpate Trees from any spot but time only can bring them to maturity.” |

| − | 1953: 87–88) | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Shippen, Thomas Lee, 31 | + | [[File:0036.jpg|thumb|Fig. 8, Thomas Lee Shippen, Plan of Westover, 1783. The grove is marked at “&c” at upper left quadrant.]] |

| + | *Shippen, Thomas Lee, December 31, 1783, describing Westover, seat of William Byrd III, on the James River, VA (1952: n.p.)<ref>Thomas Lee Shippen, ''Westover Described in 1783: A Letter and Drawing Sent by Thomas Lee Shippen, Student of Law in Williamsburg, to His Parents in Philadelphia'' (Richmond, VA: William Byrd Press, 1952), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/3IWWPMJ5 view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | :“The crooked line markd x [on the accompanying drawing] shews you where the garden is which is very large and exceedingly beautiful indeed. The one opposite to it &c is the place where there is a pretty '''grove''' neatly kept, from which the walk thro’ one of the pretty [[gate]]s markd g leads you to the improved grounds before the house.” [Fig. 8] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Washington, George, 1785 and 1786, describing [[Mount Vernon]], [[plantation]] of George Washington, Fairfax County, VA (Jackson and Twohig, eds., 1978: 4:99, 107, 304)<ref>George Washington, ''The Diaries of George Washington'', ed. Donald Jackson and Dorothy Twohig, 6 vols (Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia, 1978), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/9ZIIR3FT view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“[March 7, 1785] Planted all my Cedars, all my Papaw, and two Honey locust Trees in my [[Shrubberies]] and two of the latter in my '''groves'''—one at each (side) of the House and a large Holly tree on the Point going to the Sein landing. . . | |

| − | + | :“Finished Plowing the Ground adjoining the Pine '''Grove''', designed for Clover & Orchard grass Seed. . . | |

| − | + | :“[March 24, 1785] Finding the Trees round the [[Walk]]s in my wildernesses rather too thin I doubled them by putting (other Pine) trees between each. | |

| − | + | :“Laid off the [[Walk]]s in my '''Groves''', at each end of the House. . . | |

| − | + | :“[April 6, 1786] Transplanted 46 of the large Magnolio of So. Carolina from the box brought by G. A. Washington last year—viz.—6 at the head of each of the Serpentine [[Walk]]s next the Circle—26 in the [[Shrubbery]] or '''grove''' at the South end of the House & 8 in that at the No. end. The ground was so wet, more could not at this time be planted there.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *[[Manasseh Cutler|Cutler, Manasseh]], July 13, 1787, describing the [[State House Yard]], Philadelphia, PA (1987: 1:262)<ref name="Cutler">William Parker Cutler, ''Life, Journals, and Correspondence of Rev. Manasseh Cutler, LL.D.'' (Athens: Ohio University Press, 1987), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/3PBNT7H9 view on Zotero]. | |

| − | + | </ref> | |

| − | + | :“It was so lately laid out in its present form that it has not assumed that air of grandeur which time will give it. The trees are yet small, but most judiciously arranged. The artificial [[mound]]s of earth, and depressions, and small '''groves''' in the [[square]]s have a most delightful effect.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *[[Manasseh Cutler|Cutler, Manasseh]], July 14, 1787, describing [[Gray's Garden|Gray’s Tavern]], Philadelphia, PA (1987: 1:275–77)<ref name="Cutler"></ref> | |

| − | + | :“As we were walking on the northern side of the Garden, upon a beautiful glacis, we found ourselves on the borders of a '''grove''' of wood and upon the brow of a steep hill. . . At a distance, we could just see three very high arched [[bridge]]s, one beyond the other. . . We saw them through the '''grove''', the branches of the trees partly concealing them, which produced the more romantic and delightful effect. As we advanced on the brow of this hill, we observed a small foot-path, which led by several windings into the '''grove'''. We followed it; and though we saw that it was the work of art, yet it was a most happy imitation of nature. It conducted us along the declivity of the hill, which on every side was strewed with flowers in the most artless manner, and evidently seemed to be the bounty of nature without the aid of human care. At length we seemed to be lost in the [[wood]]s, but saw in the distance an antique building, to which our path led us. . . At this [[hermitage]] we came into a spacious graveled [[walk]], which directed its course further along the '''grove''', which was tall [[wood]] interspersed with close thickets of different growth. As we advanced, we found our gravel [[walk]] dividing itself into numerous branches, leading into different parts of the '''grove'''. We directed our course nearly north, though some of our company turned into the other [[walk]]s, but were soon out of sight, and thought proper to return and follow us. We at length came to a considerable [[eminence]], which was adorned with an infinite variety of [[bed]]s of flowers and artificial '''groves''' of flowering [[shrub]]s. On the further side of the eminence was a [[fence]], beyond which we perceived an extensive but narrow opening. When we came to the [[fence]], we were delightfully astonished with the [[view]] of one of the finest [[cascade]]s in America. . . The distance we judged to be about a quarter of a mile, which being seen through the narrow opening in the tall '''grove''', and the fine mist that rose incessantly from the rocks below, had a most delightful effect.” | |

| − | them by | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Adams, Abigail, November 21, 1790, describing Bush Hill, estate of Lt. Gov. James Hamilton, near Philadelphia, PA (1841: 2:207)<ref>Abigail Adams, ''Letters of Mrs. Adams, the Wife of John Adams'', ed. Charles Francis Adams, 3rd ed. (Boston: C. C. Little and J. Brown, 1841), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/5USKR5MS view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“Bush Hill, as it is called, though by the way there remains neither bush nor [[shrub]] upon it, and very few trees, except the pine '''grove''' behind it,— yet Bush Hill is a very beautiful place.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *[[Bartram, William]], 1791, describing St. Simon’s Island, GA (1928: 72–73)<ref name="Bartram">William Bartram, ''Travels through North and South Carolina, Georgia, East and West Florida'', ed. Mark Van Doren (New York: Dover, 1928), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/88NA3B2P view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“This delightful habitation was situated in the midst of a spacious '''grove''' of Live Oaks and Palms, near the strand of the bay, commanding a [[view]] of the inlet. A cool area surrounded the low but convenient buildings, from whence, through the '''groves''', was a spacious [[avenue]] into the island, terminated by a large savanna. . . | |

| − | + | :“Our rural table was spread under the shadow of Oaks, Palms, and Sweet Bays, fanned by the lively salubrious breezes wafted from the spicy '''groves'''. Our music was the responsive love-lays of the painted nonpareil, and the alert and gay mock-bird; whilst the brilliant humming-bird darted through the flowery '''groves''', suspended in air, and drank nectar from the flowers of the yellow Jasmine, Lonicera, Andromeda, and sweet Azalea.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *[[Bartram, William]], 1791, describing an Indian village in Florida (1928: 96)<ref name="Bartram"></ref> | |

| − | + | :“There was a large Orange '''grove''' at the upper end of their village; the trees were large, carefully pruned, and the ground under them clean, open, and airy.” | |

| − | |||

| − | the | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | and | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | [[File:0722.jpg|thumb|Fig. 9, Anonymous, “Barrell Farm,” Pleasant Hill, 1817. A “Poplar Grove” was located on axis with main house, between the fish pond on the Barrell property and the river.]] | |

| − | + | *Bentley, William, June 12, 1791, describing Pleasant Hill, seat of Joseph Barrell, Charlestown, MA (1962: 1:264)<ref>William Bentley, ''The Diary of William Bentley, D.D., Pastor of the East Church, Salem, Massachusetts'' (Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith, 1962), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/B63ABACF view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | :“[June] 12. Was politely received at dinner by Mr Barrell, & family, who shewed me his large & elegant arrangements for amusement, & philosophic experiments. . . His Garden is beyond any example I have seen. A young '''grove''' is growing in the back ground, in the middle of which is a [[pond]], decorated with four ships at anchor, & a marble figure in the centre. The [[Chinese manner]] is mixed with the European in the [[Summer house]] which fronts the House, below the [[Flower Garden]].” [Fig. 9] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *[[Dwight, Timothy]], 1794, describing Greenfield Hill, CT (quoted in Clarke 1993: 1:386)<ref name="Clarke">Graham Clarke, ed., ''The American Landscape: Literary Sources and Documents'', 3 vols. (East Sussex, England: Helm Information, 1993), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/TRGJ9W95 view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | ::“On yon bright plain, with beauty gay, | |

| − | + | ::Where waters wind, and cattle play, | |

| − | + | ::Where gardens, '''groves''', and [[orchard]]s bloom, | |

| − | + | ::Unconscious of her coming doom, | |

| − | + | ::Once Fairfield smil’d. The tidy dome, | |

| − | + | ::Of pleasure, and of peace, the home, | |

| + | ::There rose; and there the glittering spire, | ||

| + | ::Secure from sacrilegious fire.” | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *La Rochefoucauld Liancourt, François Alexandre-Frédéric, duc de, 1795–97, describing Norristown, PA (1800: 1:5–6)<ref>François-Alexandre-Frédéric duc de La Rochefoucauld Liancourt, ''Travels through the United States of North America, the Country of the Iroquois, and Upper Canada, in the Years 1795, 1796, and 1797'', ed. Brisson Dupont and Charles Ponges, trans. H. Newman, 2nd ed., 4 vols. (London: R. Philips, 1800), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/SRMDWJ2M view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“Very few of them [country houses] are without a small garden; but it is rare to observe one, that has a '''grove''' adjoining, or that is surrounded with trees; it is the custom of the country to have no [[wood]] near the houses. Customs are sometimes founded in reason, but it is difficult to conjecture the design of this practice in a country, where the heat in summer is altogether intolerable, and where the structure of the houses is designedly adapted to exclude that excessive heat.* | |

| + | :“*The ''reason is'', because the country was universally wooded, when the building of these houses was first begun; and in a country thus wooded, to clear the space round the dwelling-house was just as natural, as to plant round the house in a country otherwise bare of [[wood]].— ''Translator''.” | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Anonymous, June 14, 1800, describing in the ''Federal Gazette'' the estate of Adrian Valeck, Baltimore, MD (quoted in Sarudy 1989: 136)<ref>Barbara Wells Sarudy, “Eighteenth-Century Gardens of the Chesapeake,” ''Journal of Garden History'' 9 (1989): 104–59, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/PGSNXHMJ view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“A large garden in the highest state of cultivation, laid out in numerous and convenient [[walk]]s and [[square]]s bordered with [[espalier]]s, on which. . . the greatest variety of fruit trees, the choicest fruits from the best [[nursery|nurseries]] in this country and Europe have been attentively and successfully cultivated. . . Behind the garden in a '''grove''' and [[shrubbery]] or bosquet planted with a great variety of the finest forest trees, oderiferous & other flowering shrubs etc.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *[[Manasseh Cutler|Cutler, Manasseh]], January 2, 1802, describing [[The Woodlands]], [[seat]] of [[William Hamilton]], near Philadelphia, PA (1987: 2:145)<ref name="Cutler"></ref> | |

| − | + | :“We then walked over the [[pleasure ground]]s in front and a little back of the house. It is formed into [[walk]]s, in every direction, with [[border]]s of flowering [[shrub]]s and trees. Between are [[lawn]]s of green grass, frequently mowed to make them convenient for walking, and at different distances numerous copse of native trees, interspersed with artificial '''groves''', which are set with trees collected from all parts of the world.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *[[Thomas Jefferson|Jefferson, Thomas]], 1807, describing [[Monticello]], [[plantation]] of [[Thomas Jefferson]], Charlottesville, VA (quoted in Nichols and Griswold 1978: 111)<ref>Frederick Doveton Nichols and Ralph E. Griswold, ''Thomas Jefferson, Landscape Architect'' (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1978), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/RUZC4Q3D view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“The canvas at large [of a Garden or pleasure ground] must be '''Grove''', of the largest trees, (poplar, oak, elm, maple, ash, hickory, chestnut, Linden, Weymouth pine, sycamore) trimmed very high, so as to give it the appearance of open ground, yet not so far apart but that they may cover the ground with close shade.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *[[Latrobe, Benjamin Henry]], March 17, 1807, describing the White House, Washington, DC (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation) | |

| − | + | :“In removing the ground, it would certainly be necessary to go down in front of the colonnade to the level of about one foot below the bases of the [[Column]]s but, it will certainly not deprive this colonnade of any part of its beauty to pass behind a few gentle Knolls and '''groves''' or [[Clump]]s in its front, and much expense of removing earth would be thereby saved.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Smith, Margaret Bayard, August 1, 1809, describing [[Monticello]], [[plantation]] of [[Thomas Jefferson]], Charlottesville, VA (1906: 73)<ref>Margaret Bayard Smith, ''The First Forty Years of Washington Society'', ed. Gaillard Hunt (New York: Charles Scribner’s, 1906), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/FTDFHRFH view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“As we passed the graveyard, which is about half way down the mountain, in a sequestered spot, he told me he there meant to place a small gothic building,—higher up, where a beautiful little [[mound]] was covered with a '''grove''' of trees, he meant to place a monument to his friend Wythe.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | describing the | + | *Cuming, Fortesque, 1810, describing a seat in Pittsburgh, PA (1810: 227)<ref>Fortescue Cuming, ''Sketches of a Tour to the Western Country'' (Pittsburgh: Cramer, Spear and Eichbaum, 1810), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/EFUIGI3M view on Zotero].</ref> |

| − | + | :“What adds to the beauty of Mr. Tannehill’s [[seat]] is, a handsome '''grove''' of about two acres of young black oaks, northwest of his dwelling, through the middle of which runs a long frame [[bowery]], on whose end fronting the road, is seen this motto, ‘''1808, Dedicated to Virtue, Liberty, and Independence''’ Here a portion of the citizens meet on each 4th of July, to hail with joyful hearts the day that gave birth to the liberties and happiness of their country. On the opposite side of the road to the [[bowery]], is a spring issuing from the side of the hill, whose water trickles down a rich clover patch, through which is a deep hollow with several small [[cascade]]s, overhung with the willow, and fruit trees of various kinds.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *[[Peale, Charles Willson]], July 22, 1810, describing [[Belfield]], estate of [[Charles Willson Peale]], Germantown, PA (Miller et al., eds., 1991: 3:51)<ref>Lillian B. Miller et al., eds., ''The Selected Papers of Charles Willson Peale and His Family'', vol. 3, ''The Belfield Farm Years, 1810–1820'' (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1991), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/IZAKPCBG view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“I am often pleased with the solemn '''groves''' skirting [[meadow]]s in majestic silence and cool appearance.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | [[File:1051.jpg|thumb|Fig. 10, Daniel Wadsworth, “Monte Video, Approach to the House,” in Benjamin Silliman, ''Remarks Made on a Short Tour between Hartford and Quebec, in the Autumn of 1819'' (1824), pl. opp. 16.]] | |

| + | *Silliman, Benjamin, 1819, describing Monte Video, property of Daniel Wadsworth, Avon, CT (1824: 14–15)<ref>Benjamin Silliman, ''Remarks Made on a Short Tour between Hartford and Quebec, in the Autumn of 1819'' (New Haven, CT: S. Converse, 1824), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/B5VWTWM5 view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | :“From the boat or [[summerhouse|summer house]], several paths diverge. . . the first passes round the [[lake]], and generally out of sight of it, for a quarter of a mile, until descending a very steep bank, through a '''grove''' of evergreens, so dark as to be almost impervious to the rays of the sun, even at noon day.” [Fig. 10] | ||

| − | describing the | + | *Bryant, William Cullen, August 25, 1821, describing the Vale, estate of Theodore Lyman, Waltham, MA(1975: 108–9)<ref>William Cullen Bryant, ''The Letters of William Cullen Bryant'', ed. William Cullen II Bryant and Thomas G. Voss (New York: Fordham University Press, 1975), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/3X5XUJ6A/ view on Zotero].</ref> |

| − | ( | + | :“He took me to the seat of Mr. Lyman. . . It is a perfect paradise. . . A hard rolled [[walk]], by the side of a brick [[wall]]. . . led us to a '''grove''' of young forest trees on the top of [an] [[eminence]] in the midst of which was a [[Chinese_manner|Chinese]] [[temple]].” |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Anonymous, April 17, 1829, “Neglected Grave Yards” (''New England Farmer'' 7: 307)<ref>“Neglected Grave Yards,” ''New England Farmer, and Horticultural Journal'' 7, no. 39 (April 17, 1829): 307, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/BRBQGV63 view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| + | :“I wish to call your attention to the subject of repairing, clearing, and ornamenting the burial grounds of New England. These enclosures are commonly neglected by the sexton, and present to the curious traveller, an ugly collection of slate slabs, of weeds, and rank or dried grass. A small effort in each sexton or clergyman, would suffice to awaken attention, to bring to the recollection of some, and to the fancy of all, a scene which every village should present, a '''grove''' sacred to the dead and to their recollection, to calm religious conversation, and to melancholy musing—inclosed with [[shrubbery]], and evergreen, and dignified by the lofty maple, and elm, and oak, and guarded by a living [[hedge]] of hawthorn. | ||

| + | :“Every sexton should procure some oak, elm, and locust seed, and make it a part of his vocation to scatter it for chance growth.” | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Ingraham, Joseph Holt, 1835, describing a village near New Orleans, LA (1835: 1:81–82)<ref>Joseph Holt Ingraham, ''The South-West'', 2 vols. (New York: Harper, 1835), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/DTFA8CCM view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“On the left and diagonally from the dwelling house we noticed a very neat, pretty village, containing about forty small snow-white cottages, all precisely alike, built around a pleasant [[square]], in the centre of which, was a '''grove''' or cluster of magnificent sycamores.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Martineau, Harriet, May 4, 1835, describing New Orleans, LA (1838: 1:274)<ref>Harriet Martineau, ''Retrospect of Western Travel'', 2 vols. (London: Saunders and Otley, 1838), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/KEG83GHS view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“In the neighbourhood of Mobile, my relative, who has a true English love of gardening, had introduced the practice [of gardens]; and I there saw villas and cottages surrounded with a luxuriant growth of Cherokee roses, honeysuckles, and myrtles, while '''groves''' of orange-trees appeared in the background.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Breck, Joseph, February 1, 1836, describing Bellmont Place, residence of John Perkins Cushing, Watertown, MA (''Horticultural Register'' 2: 43)<ref>Joseph Breck, “Gardens, Hot-Houses, &c., in the Vicinity of Boston,” ''Horticultural Register, and Gardener’s Magazine'' 2 (February 1, 1836): 41–47, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/IK2ZAWSC view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“The approach to the mansion from the road is by a winding [[avenue]] through a fine '''grove''' of ancient deciduous trees. The first view of the garden and ranges of glass structure, as we emerged from the '''grove''', was truly magnificent.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *B., J., October 1, 1836, “Horticulture in Maine” (''Horticultural Register'' 2: 381)<ref>J. B., “Horticulture in Maine,” ''Horticultural Register, and Gardener’s Magazine'' 2 (October 1, 1836): 380–86, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/HDTD7A9V view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| + | :“We noticed with pleasure, that most of the vicinity of Portland was highly decorated with numerous shade trees, in '''groves''', groups, and single, which the good taste of the proprietors of the soil have spared as yet. Near the city is an extensive, and one of the finest '''groves''' of oaks we have ever seen.” | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Featherstonhaugh, George William, August 20, 1837, describing Pendleton, SC (quoted in Jones 1957: 126–27)<ref>Katharine M. Jones, ''The Plantation South'' (New York: Bobbs-Merrill, 1957), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/AT62T7KC view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“I went in the carriage with the ladies to the Episcopal Church at Pendleton, a neat [[temple]] prettily situated in a shady '''grove'''.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Hovey, C. M. (Charles Mason), November 1839, describing Elfin Glen, residence of P. Dodge, Salem, MA (''Magazine of Horticulture'' 5: 404)<ref>Charles Mason Hovey, “Notices of Gardens and Horticulture, in Salem, Mass.,” ''Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs'' 5, no. 11 (November 1839): 401–16, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/25HW5NZ9 view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“In front of the cottage, and extending to the limits of the garden, on the west, ornamental [[shrub]]s and forest trees are thickly planted, and are making a rapid and healthy growth; in a few years they will form a dense and shady '''grove'''.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Willis, Nathaniel Parker, 1840, describing [[Mount Auburn Cemetery]], Cambridge, MA (1840: 348)<ref>Nathaniel Parker Willis, ''American Scenery; Or, Land, Lake, and River: Illustrations of Transatlantic Nature'', 2 vols. (London: George Virtue, 1840), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/T5CMW67U/ view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“This [[picturesque]] and beautiful [[burial ground|burial-place]] occupies a '''grove''', formerly an academic and sylvan retreat for the students of Harvard College, near by.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | and | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Bryant, William Cullen, April 24, 1843, describing St. Anastasia, FL (quoted in Clarke 1993: 2:161)<ref name="Clarke"></ref> | |

| − | + | :“In another part of the same island, which we visited afterward, is a dwelling-house situated amid orange-'''groves'''. Closely planted rows of the sour orange, the native tree of the country, intersect and shelter [[orchard]]s of the sweet orange, the lemon, and the lime.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | [[File:1097.jpg|thumb|Fig. 11, Thomas S. Sinclair, “Plan of the [[Pleasure ground/Pleasure garden|Pleasure Grounds]] and Farm of the [[Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane]] at Philadelphia,” in Thomas S. Kirkbride, ''American Journal of Insanity'' 4, no. 4 (April 1848): pl. opp. 280.]] | |

| − | the | + | *Kirkbride, Thomas S., April 1848, describing the [[pleasure ground]]s and farm of the [[Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane]], Philadelphia, PA (''American Journal of Insanity'' 4: 348)<ref>Thomas S. Kirkbride, “Description of the Pleasure Grounds and Farm of the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane, with Remarks,” ''American Journal of Insanity'' 4, no. 4 (April 1848): 347–54, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/9RWM2FH8 view on Zotero].</ref> |

| − | + | :“The remainder of the grounds on this side of the [[deer-park]] is specially appropriated to the use of the male patients. In this division is a fine '''grove''' of large trees, several detached [[clump]]s of various kinds and a great variety of single trees standing alone or in [[avenue]]s along the different [[walk]]s, which, of brick, gravel or tan, are for the men, more than a mile and a quarter in extent. The '''groves''' are fitted up with seats and [[summer house]]s, and have various means of exercise and amusement connected with them. . . | |

| + | :“The work-shop and lumber-yard are just within the main entrance on the west—adjoining which is a fine '''grove''', in which is the gentlemen’s ten-pin alley.” [Fig. 11] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Hovey, C. M. (Charles Mason), March 1849, describing the residence of Gen. Elias W. Leavenworth, Syracuse, NY (''Magazine of Horticulture'' 15: 98)<ref>C. M. Hovey, “Notes of a Visit to Several Gardens & Nurseries in Western New York,” ''Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs'' 15, no. 3 (March 1849): 97–105, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/T6A833UU view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“. . . this [the fruit garden] and the house occupy about half of the ground: the other half has been made a most beautiful '''grove'''; this was done by a judicious cutting away of whole trees in some places, and by pruning and thinning the branches in others, leaving the whole a [[picturesque]] mass, which years of time and labor could not have produced.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Gordon, Alexander, June 1849, describing the residence of Mr. Valcouraam, near New Orleans, LA (''Magazine of Horticulture'' 15: 247–48)<ref>Alexander Gordon, “Remarks on Gardens and Gardening in Louisiana,” ''Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs'' 15, no. 6 (June 1849): 245–49, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/HNZQV4FE/q/gardens%20and%20gardening view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“For instance, within a few minutes walk from where I now write, I could find magnificent '''groves''' of magnolias (now in full bloom,) with an abundance of choice trees and [[shrub]]s. All that would be required to form the scene into a perfect ''facsimile'' of an English [[shrubbery]] would be to introduce [[walk]]s, and judiciously thin out and regulate the mass.” | |

| − | |||

| − | and | ||

| − | from the | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Committee on the Capitol Square, Richmond City Council, July 26, 1851, describing John Notman's plans for the Capitol Square, Richmond, VA (quoted in Greiff 1979: 162)<ref>Constance Greiff, ''John Notman, Architect, 1810–1865'' (Philadelphia: Athenaeum of Philadelphia, 1979), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/SXT2RI6Z view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“The most beautiful feature of the contemplated alterations of the [[Square]], however, will be found in the arrangement of the trees and [[shrubbery]]. Instead of planting these in parallel rows, like an ordinary [[orchard]] some attention will be paid to [[landscape gardening]]—'''groves''', [[arbour]]s, [[parterre]]s, and [[fountain]]s will combine to render the [[Square]] a place of delightful resort.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | and | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *[[Andrew Jackson Downing|Downing, Andrew Jackson]], August 1851, “The New-York Park” (''Horticulturist'' 6: 346–47)<ref>Andrew Jackson Downing, “The New-York Park,” ''Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste'' 6, no. 8 (August 1851): 345–49, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/2XEW44DT view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“That because it is needful in civilized life for men to live in cities,—yes, and unfortunately too, for children to be born and educated without a daily sight of the blessed horizon,—it is not, therefore, needful for them to be so miserly as to live utterly divorced from all pleasant and healthful intercourse with gardens and green fields. He [Mayor Kingsland] informs them that cool umbrageous '''groves''' have not forsworn themselves within town limits, and that half a million of people have a ''right'' to ask for the ‘greatest happiness’ of [[park]]s and [[pleasure ground]]s, as well as for paving stones and gas lights. . . | |

| − | + | :“In the broad area of such a verdant zone would gradually grow up, as the wealth of the city increases, winter gardens of glass, like the great Crystal Palace, where the whole people could luxuriate in '''groves''' of the palms and spice trees of the tropics, at the same moment that sleighing parties glided swiftly and noiselessly over the snow covered surface of the country-like [[avenue]]s of the wintry park without.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ===Citations=== | |

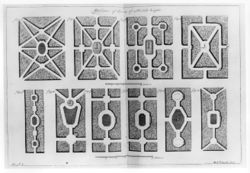

| − | + | [[File:1054.jpg|thumb|Fig. 12, Michael van der Gucht, “Designs of Groves of a Middle Height,” A.-J. Dézallier d’Argenville, ''The Theory and Practice of Gardening'' (1712), pl. 4c, n.p.]] | |

| − | + | *Dezallier d’Argenville, Antoine-Joseph, 1712, ''The Theory and Practice of Gardening'' (1712: 48–49)<ref>A.-J. (Antoine Joseph) Dézallier d’Argenville, ''The Theory and Practice of Gardening; Wherein Is Fully Handled All That Relates to Fine Gardens, . . . Containing Divers Plans, and General Dispositions of Gardens'', trans. John James (London: Geo. James, 1712), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/RNT8ZVZ8 view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“''The French'' call a '''Grove''' ''Bosquet'', from the ''Italian'' Word ''Bosquetto'', a little [[Wood]] of small Extent, as much as to say, a Nosegay, or Bunch of Green. | |

| − | they | + | :“''[[WOOD]]S'' and '''Groves''' make the ''Relievo'' of Gardens, and serve infinitely to improve the flat Parts, as [[Parterre]]s and [[Bowling-green]]s. Care should be taken to place them so, that they may not hinder the Beauty of the [[Prospect]]. . . |

| + | :“Their most usual Forms are the Star, the direct Cross, S. ''Andrew’s'' Cross, and the Goose-Foot; they nevertheless admit the following Designs, as Cloisters, [[Labyrinth]]s, Quincunces, [[Bowling-green]]s, Halls, Cabinets, circular and [[square]] Compartiments, Halls for Comedy, Covered Halls, Natural and Artificial [[Arbor]]s, [[Fountain]]s, Isles, [[cascade|Cascades]], Water-Galleries, Green-Galleries, ''&c''.” [Fig. 12] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Langley, Batty, 1728, ''New Principles of Gardening'' (1728; repr., 1982: Introduction, 195–203)<ref>Batty Langley, ''New Principles of Gardening, or The Laying out and Planting Parterres, Groves, Wildernesses, Labyrinths, Avenues, Parks, &c'' (London: A. Bettesworth and J. Batley, etc., 1728; repr. New York: Garland, 1982), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/MRDTAEKC view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“Their [Nobility and Gentry of England] ''Wildernesses'' and '''''Groves''''' (when they planted any) were always placed at the most remote Parts of the Garden: So that before we can enter them, in the ''Heat of Summer'', when they are most useful, we are obliged to pass thro’ the ''scorching Heat of the Sun''. | |

| − | + | :“Indeed, ’tis oftentimes necessary to place '''''Groves''''' and open ''Wildernesses'' in such remote Parts of Gardens, from whence ''pleasant [[Prospect]]s are taken''; but then we should always take care to plant ''proportionable [[Avenue]]s'' leading from the House to them, under whose ''Shade'' we might with Pleasure pass and repass at any time of the Day. . . | |

| − | + | :“Their '''GROVES''' (whenever they planted any) were always regular, ''like unto [[Orchard]]s'', which is entirely wrong; for when we come to ''copy'', or ''imitate Nature'', we should trace her Steps with the greatest Accuracy that can be. And therefore when we plant '''''Groves''' of Forest or other Trees'', we have nothing more to regard, than that the outside Lines be agreeable to the Figure of the '''Grove''', and that no three Trees together range in a strait [''sic''] Line; excepting now and then by Chance, to cause Variety. . . | |

| + | :“''General'' DIRECTIONS, ''&c''. | ||

| + | :“I. THAT the grand Front of a Building lie open upon an elegant [[Lawn]] or Plain of Grass, adorn’d with beautiful [[Statue]]s, (of which hereafter in their Place,) terminated on its Sides with open '''Groves'''. . . | ||

| + | :“VIII. That Shady [[Walk]]s be planted from the End-[[View]]s of a House, and terminate in those open '''Groves''' that enclose the Sides of the plain [[Parterre]], that thereby you may enter into immediate Shade, as soon as out of the House, without being heated by the Scorching Rays of the Sun. . . | ||

| + | :“IX. That all the Trees of your Shady [[Walk]]s and '''Groves''' be planted with Sweet-Brier, White Jessemine, and Honey-Suckles, environ’d at Bottom with a small Circle of Dwarf-Stock, Candy-Turf, and Pinks. . . | ||

| + | :“XVIII. That the Intersection of [[Walk]]s be adorn’d with [[Statue]]s, large open Plains, '''Groves''', Cones of Fruit, of Ever-Greens, of Flowering [[Shrub]]s, of Forest Trees, [[Bason]]s, [[Fountain]]s, [[Sun-Dial]]s, and [[Obelisk]]s. . . | ||

| + | :“XXV. '''Groves''' of Standard Ever-Greens, as Yew, Holly, Box, and Bay-Trees, are very pleasant, especially when a delightful [[Fountain]] is plac’d in their Center. . . | ||

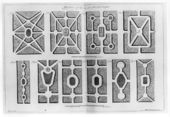

| + | [[File:1053.jpg|thumb|Fig. 13, Batty Langley, “Design of a ''rural Garden'', after the new manner,” in ''New Principles of Gardening'' (1728), pl. III, opp. 208.]] | ||

| + | :“XXXII. In the Planting of '''Groves''', you must observe a regular Irregularity; not planting them according to the common Method like an [[Orchard]], with their Trees in straight Lines ranging every Way, but in a rural Manner, as if they had receiv’d their Situation from Nature itself. | ||

| + | :“XXXIII. Plant in and about your several '''Groves''', and other Parts of your Garden, good store of Black-Cherry and other Trees that produce Food for Birds, which will not a little add to the Pleasure thereof. . . | ||

| + | :“XXXV. The several kinds of Forest-Trees make beautiful '''Groves''', as also doth many Ever-Greens, or both mix’d together; but none more beautiful than that noble Tree the Pine.” [Fig. 13] | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Miller, Philip, 1754, ''The Gardeners Dictionary'' (1754; repr., 1969: 588–90)<ref>Philip Miller, ''The Gardeners Dictionary'' (New York: Verlag Von J. Cramer, 1969), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/356Q24EP view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“'''GROVES''' are the greatest Ornaments to a Garden; nor can a Garden be complete which has not one or more of these. In small Gardens there is scarce room to admit of '''Groves''' of any Extent; yet in these there should be at least one contrived, which should be as large as the Ground will allow it: and where these are small, there is more Skill required in the Disposition, to give them the Appearance of being larger than they really are. . . | |

| + | :“These '''Groves''' are not only great Ornaments to Gardens, but are also the greatest Relief against the violent Heats of the Sun, affording Shade to walk under, in the hottest Part of the Day, when the other Parts of the Garden are useless; so that every Garden is defective which has not Shade. | ||

| + | :“'''Groves''' are of two Sorts: viz. open and close '''Groves''': Open '''Groves''' are such as have large shady Trees, which stand at such Distances, as that their Branches may approach so near each other, as to prevent the Rays of the Sun from penetrating through them: but as such Trees are a long time in growing to a proper Size for affording a Shade; so where new '''Groves''' are planted, the Trees must be placed closer together, in order to have Shade as soon as possible: but in planting of these '''Groves''', it is much the best Way to dispose all the Trees irregularly, which will give them a greater Magnificence, and also form a shade sooner, than when the Trees are planted in Lines; for when the Sun shines between the Rows of Trees, as it must do some Part of the Day in Summer, the [[Walk]]s between them will be exposed to the Heat, at such times, until the Branches of these Trees meet, whereas, in the irregular [[Plantation]]s, the Trees intervene, and obstruct the direct Rays of the Sun. | ||

| + | :“When a Person, who is to lay out a Garden, is so happy as to meet with large full-grown Trees upon the Spot, they should remain inviolate, if possible; for it will be better to put up with many Inconveniencies, than to destroy these. . . so that nothing but that of offending the Habitation, by being so near as to occasion great Damps, should tempt the cutting of them down. . . | ||

| + | :“Close '''Groves''' have frequently large Trees standing in them; but the Ground is filled under these with [[Shrub]]s, or Underwood; so that the [[Walk]]s which are made in them are private, and screened from Winds; whereby they are rendered agreeable for walking, at such times when the Air is too violent or cold for walking in the more exposed Parts of the Garden. | ||

| + | :“These are often contrived so as to bound the open '''Groves''', and frequently to hide the [[Wall]]s, or other Inclosures of the Garden: and when they are properly laid out, with dry [[Walk]]s winding through them, and on the Sides of these sweet-smelling [[Shrub]]s and Flowers irregularly planted, they have a charming Effect: for here a Person may walk in private sheltered from the Inclemency of cold or violent Winds; and enjoy the greatest Sweets of the vegetable Kingdom: therefore where it can be admitted, if they are continued round the whole Inclosure of the Garden, there will be a much greater Extent of [[Walk]]: and these Shrubs will appear the best Boundary, where there are not fine [[Prospect]]s to be gained. | ||

| + | :“These close '''Groves''' are by the ''French'' termed ''Bosquets'', from the ''Italian'' word ''Bosquetto'', which signifies a little [[Wood]]: and in most of the ''French'' Gardens there are many of them planted; but these are reduced to regular Figures, as Ovals, Triangles, [[Square]]s, and Stars: but these have neither the Beauty or Use which those have that are made irregularly, and whose [[Walk]]s are not shut up on each Side by [[Hedge]]s, which prevents the Eye from seeing the [[Quarter]]s; and these want the Fragrancy of the Shrubs and Flowers, which are the great Delight of these private [[Walk]]s; add to this, the keeping of the [[Hedge]]s in good Order is attended with a great Expence; which is a capital Thing to be considered in the making of Gardens.” | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Ware, Isaac, 1756, ''A Complete Body of Architecture'' (1756: 649–51)<ref>Isaac Ware, ''A Complete Body of Architecture'' (London: T. Osborne and J. Shipton, 1756), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/2EK2USKV view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“The disposition of '''groves''' is a consideration not enough regarded: we err in it greatly; we plant the trees too close, and we make the [[walk]]s too narrow. The person who goes into them to be free from the sun is choaked for want of air; and the same closeness occasions a continual damp, very dangerous at such seasons. Every thing in them is gloomy and disagreeable. Instead of this, a kind of cheerfulness may be diffused even there; and we may have solitude, shade, and retirement, without a savage darkness of dreary wet. . . | |

| − | + | :“Let the [[plantation]] be made of selected trees, as we have proposed, and let them have good distance: they will grow more vigorously, and the [[walk]] will be more wholesome. | |

| − | + | :“This space of planting will also give reason for flowering [[shrub]]s, which may be scattered here and there about the [[walk]], and will thrive nearly as well as in the open air. | |

| + | :“Thus may the '''groves''' be constructed ornamentally to the other parts of the garden, elegant and pleasing in themselves, and fit to form recesses in which to place [[Statue|statutes]] [''sic''], [[temple]]s, and other structures. . . | ||

| + | :“A ragged outside of a '''grove''' contrasts the trim cheerfulness of an even [[walk]]; and one gives the other lustre. The only rule is, that they be used with moderation and discretion; for they must be considered as foils and extravagancies, not as the essential and regular part of a garden.” | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | “The | + | *Whately, Thomas, 1770, ''Observations on Modern Gardening'' (1770; repr., 1982: 36, 46–48)<ref>Thomas Whately, ''Observations on Modern Gardening'', 3rd ed. (1770; repr., London: Garland, 1982), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/QKRK8DCD/ view on Zotero].</ref> |

| − | within the | + | :“Every [[plantation]] must be either a ''[[wood]]'', a '''''grove''''', a ''[[clump]]'', or a ''single tree''. “A wood is composed of both trees and underwood, covering a considerable space. A '''grove''' consists of trees without underwood; a [[clump]] differs from either only in extent. . . |

| − | + | :“The prevailing character of a [[wood]] is generally grandeur. . . But the character of a '''grove''' is ''beauty''; fine trees are lovely objects; a '''grove''' is an assemblage of them; in which every individual retains much of its own peculiar elegance; and whatever it loses, is transferred to the superior beauty of the whole. To a '''grove''', therefore, which admits of endless variety in the disposition of the trees, differences in their shapes and their greens are seldom very important, and sometimes they are detrimental. . . | |

| − | + | :“Though a '''grove''' be beautiful as an object, it is besides delightful as a spot to [[walk]] or to sit in; and the choice and the disposition of the trees for effects ''within'', are therefore a principal consideration. Mere irregularity alone will not please; strict order is there more agreable than absolute confusion; and some meaning better than none. . . . The distances therefore should be strikingly different: the trees should gather into groupes, or stand in various irregular lines, and describe several figures: the intervals between them should be contracted both in shape and in dimensions: a large space should in someplaces be quite open: in others the trees should be so close together, as hardly to leave a passage between them; and in others as far apart as the connexion will allow. In the forms and the varieties of these groupes, these lines, and these openings, principally consists the interior beauty of a '''grove'''.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Squibb, Robert, 1787, ''The Gardener’s Calendar for South Carolina, Georgia, and North Carolina'' (1787; repr., 1980: 51)<ref>Robert Squibb, ''The Gardener’s Calendar for South-Carolina, Georgia, and North Carolina'' (1787; repr., Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1980), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/keywords_in_early_american_landscape_design/items/itemKey/98BZAHB3 view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“If you plant the orange trees for a [[hedge]], about ten feet will be a good distance; but if intended for an [[orchard]] or a '''grove''', twenty feet will not be too much.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Sheridan, Thomas, 1789, ''A Complete Dictionary of the English Language'' (1789: n.p.)<ref>Thomas A. Sheridan, ''A Complete Dictionary of the English Language, Carefully Revised and Corrected by John Andrews'', 5th ed. (Philadelphia: William Young, 1789), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/T5GU4CBQ view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“'''GROVE''', gro’ve. s. A [[walk]] covered by trees meeting above.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Deane, Samuel, 1790, ''The New-England Farmer'' (1790: 116)<ref>Samuel Deane, ''The New-England Farmer, or Georgical Dictionary'' (Worcester, MA: Isaiah Thomas, 1790), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/S8QQDHP6 view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“'''GROVE''', a row or [[walk]] of trees planted close, for ornament and shade. | |

| − | + | :“Formerly a '''grove''' made in regular lines, was considered as most ornamental. But modern improvers are rather disgusted with the uniformity of a '''grove''', and prefer those which appear as if they were the work of nature or chance. As taste alters from time to time, I shall not undertake to determine which are most grand or beautiful. As my great object is real improvement and advantage, I shall here attend to '''groves''' in regular lines. | |

| − | + | :“'''Groves''' in gardens are both ornamental and useful. They shade the [[walk]]s in the borders; so that we may walk in gardens with pleasure, in the hottest part of the day. It is scarcely needful to say these garden '''groves''' should consist of fruit-trees; and they should be of the smaller kinds, in a garden of a small size. A double row has the best effect, one near the [[wall]], the other on the opposite side of the [[walk]]. | |

| − | + | :“In other situations '''groves''' of larger trees are preferred. Lanes and [[avenue]]s leading to mansion houses and other buildings, may be ornamented with rows of trees, either on one, or on both sides: If only on one, it should be the southermost, on account of the advantage of shade. . . | |

| − | + | :“It would be advantageous to the publick, as well as to the owners of adjoining farms, if all our roads were lined with '''groves'''. They might be either within or without the fences. In the latter case, government might interpose, and secure to the planters those which stood in the roads; and oblige farmers to plant in the roads against their own lands. . . | |

| − | + | :“If the country were well stocked with these '''groves''', their perspiration would help to abate the scorching heat of the sun, by moistening the atmosphere. They would serve to impede the force of high driving winds and storms in summer, which often tear our tender vegetables, or lay our crops flat to the ground. Our buildings would be also in less danger from them. The winds in winter would not be so keen and violent. The force of sea winds on our fruit-trees would be abated. The snows that fall would be more even on the ground. Roads would be less blocked up, and seldomer rendered impassable by them. But for these last purposes, '''groves''' of evergreens will have the greatest effect. | |

| − | the | + | :“'''Groves''' should be planted thick at first, that the above advantages may be had from them while young. When the trees become so large as to be crowded, they should be thinned.” |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Marshall, William, 1803, ''On Planting and Rural Ornament'' (1803: 1:119, 145)<ref>William Marshall, ''On Planting and Rural Ornament: A Practical Treatise. . .'', 2 vols. (London: G. and W. Nicol, G. and J. Robinson, T. Cadell, and W. Davies, 1803), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/K48D75JJ view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“by ''Timber '''Grove''''' [is meant], a collection of timber trees only, placed in close order. . . | |

| − | + | :“THE TIMBER '''GROVE''' is the prevailing ''plantation'' of modern time. [[WOOD]]S or [[Copse|COPPICES]] are seldom attempted: indeed, until of late years, [[clump]]s of Scotch Firs seem to have engaged, in a great measure, the attention of the planter.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [ | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | have a | ||

| − | of | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *[[Bernard M'Mahon|M’Mahon, Bernard]], 1806, ''The American Gardener’s Calendar'' (1806: 58–59, 63–64)<ref>Bernard M’Mahon, ''The American Gardener’s Calendar: Adapted to the Climates and Seasons of the United States. Containing a Complete Account of All the Work Necessary to Be Done . . . for Every Month of the Year'' (Philadelphia: Printed by B. Graves for the author, 1806), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/HU4JIS9C view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| + | :“Straight ranges of the most stately trees, are sometimes arranged on grass-ground in different parts, in contrast with irregular plantations; and produce a most agreeable effect, which though prohibited in many [[modern style|modern]] designs, always exhibit an air of grandeur; being arranged sometimes in single rows, others double, or two ranges at certain distances, forming a grand [[walk]]; in other parts, several regular ranges of trees together in the manner of '''groves'''; the whole combined, forming a diversity, pleasing to the senses, and condusive to health, by exciting to the salutary exercise of walking. . . | ||

| + | : "The planting in '''groves''' and avenues should consist principally of the tree kind, and such as are of straight and handsome growth, with the most branchy, full, regular heads, and may be both of the deciduous and ever-green tribes; but generally arranged separately: '''groves''' and [[avenue]]s, should always be in some spacious open space, formed into grass-ground, either before or after planting the trees; and in planting the '''groves''', it is most eligible to arrange the trees in lines, in some places straight rows, others in gentle bendings, or easy sweeps, having the rows at some considerable distance, that the trees may have full scope to display their branchy heads regularly around; and in some places may have close '''groves''' to form a perfect shade. . . | ||

| + | :“It very frequently happens, that on the spot or tract, which is designed for a [[pleasure-ground]], are found large stately trees of considerable standing, properly situated to be introduced into the design; and sometimes numbers in suitable assemblages, for constituting '''groves''', or [[thicket]]s, and some for single standing groups or [[clump]]s, &c. which will prove of considerable advantage; these should be preserved with the utmost care, as it would require many years to form the like with young [[plantation]]s; and although the trees should stand ever so close, irregular, or straggling, with proper address in thinning and regulating them where necessary, they may be made to become beautifully ornamental to the place, and to prevent a considerable expense.” | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Nicol, Walter, 1812, ''The Planter’s Kalendar'' (1812: 40–42, 259–61)<ref>Walter Nicol, ''The Planter’s Kalendar'' (Edinburgh: D. Willison for A. Constable, 1812), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/NEMUHDCC view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“But '''groves''' are most generally planted in the environs of a mansion-house, in [[park]]s, and ornamental grounds; and they often form the chief artificial features of a place. Here, indeed, if the place be extensive, they are most in character; and, if contrasted with [[wood]]s, [[copse]]s, and [[thicket]]s, produce great interest. But in such cases, a '''grove''' should never be, or at least appear to be, diminutive. Its situation should always be such, as to exhibit the greatest possible magnitude, when grown up, as well as in its infancy. That the '''grove''' may appear to most advantage, it is necessary that it occupy the hang of a hill, or the swell of a rising ground: thus situated, it shows a greatly enlarged canopy of foliage. When placed on level ground, the '''grove''' necessarily requires to be more extended in length and in breadth, to produce the same good effects. | |

| − | + | :“We do not wish that our observations respecting '''grove''' plantations, should be understood as affecting those [[clump]]s, small patches of planting, or groups of trees that are merely intended to beautify the [[park]] or the [[lawn]]. Were such [[clump]]s planted for any other purpose, we doubtless would consider them as very improper appendages: but when properly pruned and thinned, they are very ornamental. The trees in such [[clump]]s, however, should never be pruned up in imitation of '''grove''' trees, but should be feathered from the bottom upwards. . . | |

| − | + | :“It has already been observed, that a '''grove''' is a [[plantation]] of trees, whatever be their kind or kinds, which are intended to be trained up with straight tall trunks. This circumstance will partly determine its extent. If the eye can penetrate through a [[plantation]], it produces a feeling of nakedness. A '''grove''', then, should be of such an extent, or so particularly situated, that, from no side shall the eye be able to penetrate to the other, even were the trees arrived at their full stature, and properly trained. This circumstance shows also the propriety of removing the situation of the '''grove''' to a considerable distance from the site of the mansion-house: It would be no mark of an improved taste to narrow the [[prospect]], by placing a '''grove''' in an improper direction. . . | |

| + | :“A '''Grove''', then, may be constituted of a mixture of trees, like ordinary mixed [[plantation]]s,—or, more properly, in the form of masses; in which respect, indeed, they may be considered as ordinary [[plantation]]s. Indeed, they differ from them hardly in any thing, excepting that the principals are to be placed rather more closely together. The principals of a deciduous '''grove''' should be placed at the distance of six feet; and the interstices filled up with nurses of larch or firs, till the trees in the whole '''grove''' be only from three to four feet apart.” | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Abercrombie, John, with James Mean, 1817, ''Abercrombie’s Practical Gardener'' (1817: 479)<ref>John Abercrombie, ''Abercrombie’s Practical Gardener Or, Improved System of Modern Horticulture'' (London: T. Cadell and W. Davies, 1817), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/TH54TADZ view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | + | :“A '''''grove''''' is distinguished from a ''[[wood]]'', by being without underwood. Like the [[clump]], it may be intersected by the garden-[[walk]]s. . . | |

| − | + | :“A '''grove''' may have a fine effect on a level; but a '''grove''' rooted in unequal ground, gently curving along the side of a hill, is capable of more various beauty, by the [[view]]s and openings from the interior.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

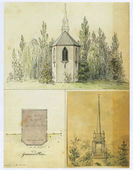

| − | + | [[File:1183.jpg|thumb|Fig. 14, [[J. C. Loudon]], "Groves", in ''An Encyclopædia of Gardening'' (1826), 943, figs. 629a and b.]] | |

| − | + | *[[J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon|Loudon, J. C. (John Claudius)]], 1826, ''An Encyclopaedia of Gardening'' (1826: 942–43)<ref>J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, ''An Encyclopaedia of Gardening; Comprising the Theory and Practice of Horticulture, Floriculture, Arboriculture, and Landscape-Gardening'', 4th ed. (London: Longman et al., 1826), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/KNKTCA4W view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | ( | + | :“6813. ''With respect to the disposition of the trees within the [[plantation]]'', they may be placed regularly in rows, [[square]]s, parallelograms, or quincunx; irregularly in the manner of groups; without undergrowths, as in '''''groves''''' (''fig. 629. a, b''); with undergrowths, as in [[wood]]s (''c''); all undergrowths, as in ''[[copse]]-[[wood]]s'' (''d''). Or they may form ''[[avenue]]s'' ''(fig. 630. a''); double [[avenue]]s (''b''); [[avenue]]s intersecting in the manner of a Greek cross (''c''); of a martyr’s cross (''d''); of a star (''e''); or of a cross patée, or duck’s foot (''patée d’oye'') (''f'').” [Fig. 14] |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||