Difference between revisions of "Arch"

V-Federici (talk | contribs) m (→Attributed) |

|||

| (100 intermediate revisions by 7 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | See also: [[Grotto]] | ||

| + | |||

==History== | ==History== | ||

| + | [[File:0974.jpg|thumb|left|Fig. 1, Joseph Jacques Ramée, ''Monument to the memory of general George Washington, to be erected at Baltimore'', design for the [[Washington_Monument_(Baltimore,_MD)|Washington Monument]], 1813.]] | ||

| + | [[File:0901.jpg|thumb|Fig. 2, George Bridport, Alternative designs for Washington Monument, [[Washington_Square_(Philadelphia,_PA)|Washington Square]], Philadelphia, 1816.]] | ||

| + | <span id="Chambers_cite"></span>Arch had three distinct, yet interrelated meanings or applications in the context of 18th- and 19th-century American landscape design. <span id="Webster_cite"></span>The first, which is the most heavily documented, is the use of arches in association with commemorative celebrations, as specified by [[Ephraim Chambers]] in 1741 ([[#Chambers|view text]]) and reiterated by [[Noah Webster]] in 1828 ([[#Webster|view text]]). The antecedents to this practice include the use of ancient Roman arches: large-scale, inverted U-shaped structures, erected to memorialize military victories. In North America, the building of such celebratory arches occurred most frequently in the immediate post-Revolutionary period. For specific festivities, arches were often made of impermanent materials, as in the case of the temporary arch [[Charles Willson Peale]] created for Philadelphia to mark the declaration of peace on December 2, 1783. General George Washington’s arrival in cities in the early federalist period was frequently marked by the erection of processional arches, such as the arch of cut laurel and evergreen branches erected at Gray’s Ferry in Philadelphia in 1789 [<span id="Fig_6_cite"></span>[[#Fig_6|See Fig. 6]]]. The arch, with its classical referents, was also the symbol of choice for permanent monuments to President Washington in the early 19th century. The designs of Joseph Jacques Ramée in Baltimore and of George Bridport in Philadelphia [Figs. 1 and 2] not only commemorated Washington’s achievements but also marked the entrance as a space set aside for public use. | ||

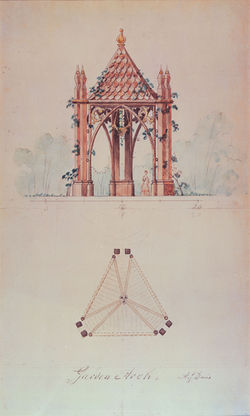

| − | Arch | + | [[File:0855.jpg|thumb|left|Fig. 3, [[Alexander Jackson Davis]], ''Garden Arch at Montgomery Place'', c. 1850.]] |

| + | These examples point to a second, closely related function of arches as spatial dividers or [[gate]]s, which also relies upon antique precedents of monumental arches marking entrances to cities or towns. <span id="Southgate_cite"></span>This practice was translated to the American context with shifts in scale and message. Eliza Southgate’s description (1802) of the garden at the Elias Hasket Derby Farm, for example, indicates that arches were used to mark three subdivisions of the landscape and to direct the visitor from the lower to the upper garden ([[#Southgate|view text]]). | ||

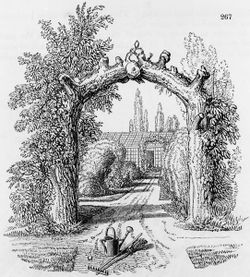

| − | + | [[File:1759.jpg|thumb|Fig. 4, [[J. C. Loudon]], “Entrance to the [[Flower_garden|Flower-garden]] at Wimbledon House,” in ''The Suburban Gardener'' (1838), p. 641, fig. 267.]] | |

| + | <span id="Peale_cite"></span>The third use of the term stemmed from its most basic meaning, summed up by [[Noah Webster|Webster]] in 1828 as “a segment of part of a circle,” translated in architecture into “a concave or hollow structure of stone or brick”. [[Charles Willson Peale|Peale’s]] description of the stone arch that he created over the stream in his garden exemplifies this definition of arch ([[#Peale|view text]]). Neither celebratory in nature nor necessarily acting as a spatial divider, the arch created a small cave-like space that [[Charles Willson Peale|Peale]] tried unsuccessfully to use as a root cellar. | ||

| − | The | + | The design or style of the arch varied by context: celebratory arches were typically classical in inspiration, but other styles, such as the Gothic and [[Chinese manner|Chinese]], were used for arches erected in gardens. The high, arching spandrels of the Gothic form allowed the erection of covered shelters without walls (with the open arches supporting the weight of the roof), as in [[Alexander Jackson Davis]]’s garden arch for [[Montgomery place|Montgomery Place]] on the Hudson [Fig. 3]. [[J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon|J. C. Loudon]] illustrated several rustic arches in his publications that were made of [[rockwork]] [<span id="Fig_9_cite"></span>[[#Fig_9|See Fig. 9]]] or rough hewn tree trunks [Fig. 4]. |

| − | + | —''Anne L. Helmreich'' | |

| − | + | <hr> | |

==Texts== | ==Texts== | ||

| + | ===Usage=== | ||

| + | [[File:0045.jpg|thumb|Fig. 5, Lester Hoadley Seller, A Reconstruction of [[Charles_Willson_Peale|Peale’s]] Transparent Triumphal Arch, 1783-84.]] | ||

| + | *[[Peale, Charles Willson]], December 8, 1783, describing his triumphal arch erected in Philadelphia, PA (quoted in Sellers 1969: 196)<ref>Charles Coleman Sellers, “Charles Willson Peale with Patron and Populace,” ''Transactions of the American Philosophical Society'' 59, no. 3 (1969), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/CKDWT3TP view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | :“I am at this time employed in painting a transparent triumphal '''Arch''' for the Public rejoicings on the peace, and very much hurried.” [Fig. 5] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | <div id="Fig_6"></div>[[File:0115.jpg|thumb|Fig. 6, James Trenchard after [[Charles_Willson_Peale|Charles Willson Peale]], “An East View of GRAY’S FERRY, near Philadelphia, with the TRIUMPHAL ARCHES, &c. erected for the Reception of [[George_Washington|General Washington]], April 20th. 1789,” in ''The Columbian Magazine'' 3 (May 1789): pl. opp. p. 282. [[#Fig_6_cite|back up to History]]]] | ||

| + | * Anonymous, May 1789, “Description of General Washington’s Reception at Gray’s Ferry on the Schuylkill, April 20” (1789: 282)<ref>Anonymous, “Account of the Preparations at Gray’s Ferry, on the River Schuylkill, and the Reception of General Washington There, April 20, 1789, on His Way to the Seat of the Federal Government, to Take upon High Office of President of the United States,” ''The Columbian Magazine'' 3, no. 5 (May 1789): 282–83, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/HDUKG8PG view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | :“A triumphal '''arch''', 20 feet high, decorated with laurel and other ever-greens, was erected at each end, (''a'' and ''b'') in a style of neat simplicity: under the '''arch''' of that at the west end (a) hung a crown of laurel, connected by a line which extended to a pine tree on the high and rocky bank of the river, where the other extremity was held by a handsome boy, beautifully robed in white linen.” [Fig. 6] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | * Bentley, William, October 22, 1790, describing the Elias Hasket Derby Farm, Peabody, MA (1962: 1:180)<ref name="Bentley">William Bentley, ''The Diary of William Bentley, D.D., Pastor of the East Church, Salem, Massachusetts'' (Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith, 1962), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/B63ABACF/ view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | :“[231] 22. . . . The Principal Garden is in three parts. . . We ascend from the house two steps in each division. The passages have no [[gate]]s, only a naked '''arch''' with a key stone frame, of wood painted white above 10 feet high.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | * Codman, John, 1791, describing the Grange, estate of Dr. John and Sarah Codman, Lincoln, MA (Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, Codman Family Manuscript Collection, box 5, folder 54) | ||

| + | |||

| + | :“1791 Accounts of Sundry Jobs . . . Dr. John Codman Esq. to Thomas Clement. . . April 20 To 40 days work on [[fence]]s and [[Espalier]]s. . . 4/6 . . . 9 . . . 0 . . . 0 . . . to 30 days work on '''Arches''' steps and [[Border]] Boards 5/ . . . 7 . . . 10 . . . 0.” | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | * Bentley, William, October 4, 1792, describing the residence of Thomas Brattle, Cambridge, MA (1962: 1:398)<ref name="Bentley"></ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | :“[58] 4. . . . I visited Mr Brattle’s Gardens, &c. at Cambridge. We first saw the [[fountain]] & [[canal]] opposite to his House, & the [[walk]] on the side of another [[canal]] in the road, flowing under an '''arch''' & in the direction of the outer [[fence]].” | ||

| + | |||

| − | + | * Pintard, John, 1801, describing New Orleans, LA (quoted in Sterling 1951: 230)<ref>David Lee Sterling, ed., “New Orleans, 1801: An Account by John Pintard,” ''Louisiana Historical Quarterly'' 34 (1951): 217–33, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/8A58JVVT view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | describing | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | :“Over some few [graves], brick '''arches''' were turned.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | * <div id="Southgate"></div>Southgate, Eliza, July 6, 1802, describing Elias Hasket Derby Farm, Peabody, MA (quoted in Kimball 1940: 75–76)<ref>Fiske Kimball, ''Mr. Samuel McIntire, Carver, the Architect of Salem'' (Portland, ME: Southworth-Anthoensen, 1940), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/I9J3RBHB view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | :“There are 3 divisions in the gardens, and you pass from the lower one to the upper thro’ several '''arches''' rising one above the other. From the lower [[gate]] you have a fine perspective view of the whole range, rising gradually until the sight is terminated by a [[hermitage]]. The [[summer house]] in the center has an '''arch''' thro’ it, with 3 doors on each side which open into little apartments and one of them opens to a staircase by which you ascend into a square room, the whole size of the building.” [[#Southgate_cite|back up to History]] | |

| − | the | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | * Anonymous, June 25, 1805, describing in the ''New York Daily Advertiser'' [[Vauxhall Garden]], New York, NY (quoted in Eberlein and Hubbard 1944: 172)<ref>Harold Donaldson Eberlein and Cortlandt Van Dyke Hubbard, “The American ‘Vauxhall’ of the Federal Era Article Stable,” ''The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography'' 68, no. 2 (April 1944): 150–74, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/RVGSTS36 view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | of | ||

| − | ( | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | :“The labour and expence of this establishment has exceeded that of any similar one in the United States. . . [that] he has at a very considerable risk and expence, procured from Europe a choice selection of [[Statue]]s and Busts, mostly from the first models of Antiquity. . . the [[walk]]s are ornamented with [[Pillar]]s, '''Arches''', Pedestals, Figures, &c. the whole of which when illuminated, cannot fail to create pleasure.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | [[File:1234_detail.jpg|thumb|200px|Fig. 7, John Vanderlyn, ''George Washington'' [detail], 1834.]] | |

| − | + | *[[Latrobe, Benjamin Henry]], March 17, 1807, in a letter to [[Thomas Jefferson]], describing the White House, Washington, DC (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation) | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | :“My idea is to carry the road below the hill under a [[Wall]] about 8 feet high opposite to the center of the president’s house. At this point, I should propose, at a future day to throw an '''Arch''', or '''Arches''' over the road in order to procure a private communication between the [[pleasure ground]] of the president’s house and the [[park]] which reaches to the river, and which will probably be also planted, and perhaps be open to the public.” [Fig. 7] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Forman, Martha Ogle, September 1, 1824, describing the entrance of the Marquis de La Fayette into Newark, NJ (1976: 187)<ref>Martha Ogle Forman, ''Plantation Life at Rose Hill: The Diaries of Martha Ogle Forman, 1814–1845'' (Wilmington, DE: Historical Society of Delaware, 1976), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/EHQ6UZGE view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | :“The entrance of La Fayette into Newark was very interesting, he was ushered in by the firing of Cannon and ringing of bells. They had erected on the [[green]] a number of '''arches''' representing the different states, all wreathed with Laurels and the effect was very beautiful.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | * <div id="Peale"></div>[[Peale, Charles Willson]], c. 1825, describing [[Belfield]], estate of Charles Willson Peale, Germantown, PA (quoted in Rudnytzky 1986: 24, 41)<ref>Kateryna A. Rudnytzky, “The Union of Landscape and Art: Peale’s Garden at Belfield” (Honors thesis, LaSalle University, 1986), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/KJK46QBZ view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | :“. . . finding a spring stream in the garden he followed it up the side of the hill, untill it become [''sic''] of some depth and among large stones—and having at this place made a considerable cavity in the bank, round the source of the Spring, to wall it up this hollow and '''arch''' it over, it was thought that it might be an excellent plan to keep cabbage and turnups &c. during the winter season, but on tryal it was found too moist and warm. . . This tryal gave the Idea of building a [[greenhouse]] journing to the '''arched''' cave—and that [[greenhouse|Green house]] keepted all exotice plants perfectly well without the aid of stoves in the severest winters. . . | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | :“. . . in a part of the Garden where a [[seat]] in the shade was often wanted, he built a shed or small room, and to hide that salt like box, and to try his art of Painting, he made the front like a [[Gate way]] with a step to form a [[seat]], and above, steps painted as representing a passage through an '''arch''' beyond on which was represented a western sky, and to ornament the upper part over the '''arch''', he painted several figures on boards cut the outlines of said figures as representing [[statue]]s in sculpture.” [[#Peale_cite|back up to History]] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | of the | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *[[Peale, Charles Willson]], c. 1825, describing Philadelphia, PA (Miller et al., eds., 2000: 5:91)<ref>Lillian B. Miller et al., eds., ''The Selected Papers of Charles Willson Peale and His Family'', vol. 5, ''The Autobiography of Charles Willson Peale'' (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2000), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/IZAKPCBG view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Peale, | + | :“When Peace was concluded between Great Britain & the united States of America, President Dickenson and the Executive Counsil employed Peale to paint a Triumphal '''Arch''' in transparent Colours. It consisted of three '''arches''', the Center '''Arch''' was 20 feet high, and the side '''arches''' each 15 feet high, and the whole length extended nearly to the width of Market street, and it was 46 feet high, independant of the statues of the 4 cardenal Virtues larger than human figures. The architecture was of the Ionic order, ornamented with reaths of Flowers, in festoons and winding round the Columes. It was also ornamented in sundry parts of the building as follows[:] |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | :“A figure of Peace, represented in a beautiful female figure, and various attendants amidst the Clouds. These were to be lighted by lights placed behind the clouds and out of the sight of the spectators, and doubtless would have had a most pleasing affect in passing down from the Top of the Presidents House to the Triumphal '''Arch''', with a fuse in the hand of Peace, which was to be directed to a fuse which would light 1100 Lamps, & illuminate the whole of the Triumphal '''Arch''' in a minute.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | the | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | [[File:1758.jpg|thumb|Fig. 8, [[J. C. Loudon]], “[[Rustic_style|Rustic]] arch and [[vase]],” in ''The Suburban Gardener'' (1838), p. 581, fig. 231.]] | |

| − | + | <div id="Fig_9"></div>[[File:1757.jpg|thumb|Fig. 9, [[J. C. Loudon]], “View of the [[Rustic_style|rustic]] arch,” in ''The Suburban Gardener'' (1838), p. 586, fig. 240. [[#Fig_9_cite|back up to History]]]] | |

| − | + | *[[J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon|Loudon, J. C. (John Claudius)]], 1838, describing the grounds of the Lawrencian Villa, residence of Mrs. Lawrence, Drayton Green, near London, England (1838: 581, 584)<ref>J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, ''The Suburban Gardener, and Villa Companion'' (London: Longman et al., 1838), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/BQVBJ48F view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | :“The next scene of interest is the Italian [[walk]], arrived at the point 8, in which, and looking back towards the paddock, we have, as a termination to one end of that walk, the rustic '''arch''' and [[vase]]. . . [Fig. 8] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | :“At 26, we have the view of the [[rustic style|rustic]] '''arch''' and Cupid. . .” [Fig. 9] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | * Knapp, Samuel, 1848, describing the house of Timothy Dexter, Newburyport, MA (1848: 19)<ref>Samuel L. Knapp, ''Life of Lord Timothy Dexter'' (Newburyport, MA: John G. Tilton, 1848), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/CHXTAR49 view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | :“Directly in front of the door of the house, on a Roman '''arch''' of great beauty and taste, stood general Washington in his military garb.” | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | [[File:0351.jpg|thumb|Fig. 10, [[A. J. Downing]], “Presidents Arch at the end of Penn<sup>a</sup> Avenue,” 1851.]] | |

| − | + | *[[Andrew Jackson Downing|Downing, Andrew Jackson]], 1851, describing plans for improving the public grounds in Washington, DC (quoted in Washburn 1967: 54)<ref>Wilcomb E. Washburn, “Vision of Life for the Mall,” ''AIA Journal'', 47, no.3 (March 1967): 52–59, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/TA59MHC7 view on Zotero].</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | :“I propose to take down the present small stone gates to the President’s Grounds, and place at the end of Pennsylvania Avenue a large and handsome '''Arch'''way of marble, which shall not only form the main entrance from the City to the whole of the proposed new Grounds, but shall also be one of the principal Architectural ornaments of the city; inside of this '''arch'''-way is a semicircle with three [[gate]]s commanding three carriage roads. Two of these lead into the Parade or President’s Park, the third is a private carriage-drive into the President’s grounds; this [[gate]] should be protected by a Porter’s lodge, and should only be open on reception days, thus making the President’s grounds on this side of the house quite private at all other times. . .” [Fig. 10] | |

| − | the | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

===Citations=== | ===Citations=== | ||

| + | * <div id="Chambers"></div>[[Chambers, Ephraim]], 1741, ''Cyclopaedia'' (1741: 1:n.p.)<ref>Ephraim Chambers, ''Cyclopaedia, or An Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences. . . '', 5th ed., 2 vols. (London: D. Midwinter et al., 1741–43) [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/PTXK378N view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| − | + | :“'''ARCH''', in architecture, is a concave structure, raised with a mould bent in form of the '''''arch''''' of a curve, and serving as the inward support of any superstructure. . . . | |

| − | |||

| − | + | :“''Triumphal'' '''ARCH''', is a [[gate]], or passage into a city, built of stone, or marble, and magnificently adorned with architecture, sculpture, inscriptions, &c. serving not only to adorn a triumph, at the return from a victorious expedition, but also to preserve the memory of the conqueror to posterity. See TRIUMPH. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | :“The most celebrated triumphal '''''arches''''', now remaining of antiquity, are that of Titus, of Septimius Severus, and of Constantine, at Rome, of which we have figures given us by Des Godetz.” [[#Chambers_cite|back up to History]] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Halfpenny, William and John, 1755, Rural | + | [[File:1676.jpg|thumb|Fig. 11, William and John Halfpenny, “A [[Chinese_manner|Chinese]] Triumphant Arch,” in ''Rural Architecture in the Chinese Taste'' (1755), pl. 14.]] |

| + | * Halfpenny, William and John, 1755, ''Rural Architecture in the Chinese Taste'' (1775; repr., 1968: 8)<ref>William and John Halfpenny, ''Rural Architecture in the Chinese Taste'' (1755; repr., Bronx, NY, and London: Benjamin Blom, 1968), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/9JKMEXVU view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| − | + | :“PLATE XIV. | |

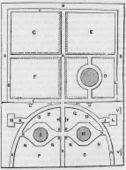

| − | + | :“Shews the Plan and Elevation of a triumphal '''Arch''', to be situated opposite the Front of a Dwelling-house, at the utmost Extent of a large [[Parterre]], through which commences a Long-[[walk]], inclosed by [[Wood]]s or other rural [[Plantation]]s. This '''Arch''' may be built in a good Manner for about 470 ''l''.” [Fig. 11] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Repton, Humphry, 1803, Observations on the | + | *Repton, Humphry, 1803, ''Observations on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening'' (1803: 144, 146)<ref>Humphry Repton, ''Observations on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening'' (London: Printed by T. Bensley for J. Taylor, 1803), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/VVQPC3BI view on Zotero].</ref> |

| − | Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening | ||

| − | + | :“If the entrance to a [[park]] be made from a town or village, the [[gate]] may with great propriety be distinguished by an '''arch'''. . . | |

| − | + | :“An '''arched''' [[gateway]] at the entrance of a place is never used with so much apparent propriety as when it forms a part of a town or village. . . | |

| − | or village | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | :“The '''arch''' should not be a mere aperture in a single [[wall]], but it should have depth in proportion to its breadth. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | :“It should have some visible and marked connexion either with a [[wall]], or with the town to which it belongs, and not appear insulated. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | “It should | + | :“It should not be placed in so low a situation that we may rather see over it than through it. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | :“Its architecture should correspond with that of the house.” | |

| − | that | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Webster, Noah, 1828, An American Dictionary of | + | * <div id="Webster"></div>[[Webster, Noah]], 1828, ''An American Dictionary of the English Language'' (1828: 1:n.p.)<ref>Noah Webster, ''An American Dictionary of the English Language'', 2 vols. (New York: S. Converse, 1828), vol. 1, [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/R6R883RR view on Zotero].</ref> |

| − | the English Language (n.p.) | ||

| − | + | :“'''ARCH''', ''n''. [See ''Arc''.] A segment or part of a circle. A concave or hollow structure of stone or brick, supported by its own curve. It may be constructed of wood, and supported by the mechanism of the work. This species of structure is much used in [[bridge]]s. | |

| − | circle. A concave or hollow structure of stone or | ||

| − | brick, supported by its own curve. It may be constructed | ||

| − | of wood, and supported by the mechanism | ||

| − | of the work. This species of structure is | ||

| − | much used in | ||

| − | “A vault is properly a broad arch. Encyc. | + | :“A vault is properly a broad '''arch'''. ''Encyc''. |

| − | “2. The space between two piers of a bridge, | + | :“2. The space between two piers of a [[bridge]], when '''arched'''; or any place covered with an '''arch'''. |

| − | when arched; or any place covered with an arch. | ||

| − | “3. Any curvature, in form of an arch. | + | :“3. Any curvature, in form of an '''arch'''. |

| − | “4. The vault of heaven, or sky. Shak. | + | :“4. The vault of heaven, or sky. ''Shak''. |

| + | |||

| + | :“''Triumphal arches'' are magnificent structures at the entrance of cities, erected to adorn a triumph and perpetuate the memory of the event.” [[#Webster_cite|back up to History]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:0911.jpg|thumb|Fig. 12, Anonymous, “Southern Villa—Romanesque Style,” in [[A. J. Downing]], ''The Architecture of Country Houses'' (1850), pl. opp. p. 353, fig. 168.]] | ||

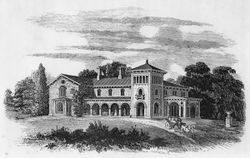

| + | *[[Andrew Jackson Downing|Downing, Andrew Jackson]], 1850, ''The Architecture of Country Houses'' (1850; repr., 1968: 353, 354)<ref>A. J. [Andrew Jackson] Downing, ''The Architecture of Country Houses; Including Designs for Cottages, Farm-Houses, and Villas'' (New York: D. Appleton, 1850; repr., New York: Da Capo, 1968), [https://www.zotero.org/groups/54737/items/itemKey/GRZPQXQI view on Zotero].</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | :“Looking at the exterior of this design, the student of expression will find it marked by dignity, variety, and harmony; . . . harmony in the predominance of the round-'''arch''' and other features of the style chosen. . . | ||

| + | |||

| + | :“We see refined culture symbolized in the round-'''arch''', with its continually recurring curves of beauty, in the spacious and elegant [[arcade]]s, inviting to leisurely conversations, in all those outlines and details, suggestive of restrained and orderly action, as contrasted with the upward, aspiring, imaginative feeling indicated in the pointed or Gothic styles of architecture. . . | ||

| + | |||

| + | :“In calling this villa ''Romanesque'', we only wish to be understood that we have gleaned from that style certain ideas of composition, which, appearing to us well suited for our purpose, we have adopted them in designing a country-house suited to a first class residence here. . .The prevalence of the round-'''arch''', of [[arcade]]s, of intersecting '''arches''', and of roofs higher than in the Grecian style, but lower than in Gothic styles, characterizes this architecture." [Fig. 12] | ||

| + | |||

| + | <hr> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Images== | ==Images== | ||

| + | ===Inscribed=== | ||

| + | <span id="roundabout_img"></span> | ||

| + | <gallery widths="170px" heights="170px" perrow="7"> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:1676.jpg|William and John Halfpenny, “A [[Chinese_manner|Chinese]] Triumphant Arch,” in ''Rural Architecture in the Chinese Taste'' (1755), pl. 14. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0977.jpg|Samuel Hill, ''View of the Triumphal Arch and Colonnade erected in Boston in honor of the President of the United States, Oct. 24, 1789'', 1790. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0887.jpg|[[Charles Willson Peale]], “A View of the Grand Civic Arch,” 1824. | ||

| + | |||

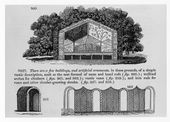

| + | Image:1707.jpg|[[J. C. Loudon]], “[[Seat]] formed of moss and hazel rods" and "Trellised arches for climbers,” in ''An Encyclopædia of Gardening'' (1834), p. 1196, figs. 960–62. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:1758.jpg|[[J. C. Loudon]], “[[Rustic_style|Rustic]] arch and [[vase]],” in ''The Suburban Gardener'' (1838), p. 581, fig. 231. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:1757.jpg|[[J. C. Loudon]], “View of the [[Rustic_style|rustic]] arch,” in ''The Suburban Gardener'' (1838), p. 586, fig. 240. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0935.jpg|Alexander Walsh, “Plan of a Garden,” in ''New England Farmer'' 19, no. 39 (March 31, 1841): 308. “TT. . . two [[seat]]s surrounded by an arched [[arbor]]" | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0855.jpg|[[Alexander Jackson Davis]], ''Garden Arch at Montgomery Place'', c. 1850. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </gallery> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Associated=== | ||

| + | <span id="roundabout_img"></span> | ||

| + | <gallery widths="170px" heights="170px" perrow="7"> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0045.jpg|Lester Hoadley Seller, A Reconstruction of [[Charles_Willson_Peale|Peale’s]] Transparent Triumphal Arch, 1783–84. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0115.jpg|James Trenchard after [[Charles_Willson_Peale|Charles Willson Peale]], “An East View of GRAY’S FERRY, near Philadelphia, with the TRIUMPHAL ARCHES, &c. erected for the Reception of General Washington, April 20th. 1789,” in ''The Columbian Magazine'' 3, no. 5 (May 1789): pl. opp. p. 282. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0911.jpg|Anonymous, “Southern Villa—Romanesque Style,” in [[A. J. Downing]], ''The Architecture of Country Houses'' (1850), pl. opp. p. 353, fig. 168. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0351.jpg|[[A. J. Downing]], “Presidents Arch at the end of Penn<sup>a</sup> Avenue,” 1851. | ||

| + | |||

| + | </gallery> | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Attributed=== | ||

| + | <span id="roundabout_img"></span> | ||

| + | <gallery widths="170px" heights="170px" perrow="7"> | ||

| + | |||

| + | File:1256.jpg|[[Robert Mills]], ''[[Monticello]]: 2nd version (west elevation)'', recto, 1803. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0974.jpg|Joseph Jacques Ramée, ''Monument to the memory of general George Washington, to be erected at Baltimore'', design for the [[Washington_Monument_(Baltimore,_MD)|Washington Monument]], 1813. | ||

| − | <gallery>< | + | Image:0901.jpg|George Bridport, Alternative designs for Washington Monument, [[Washington_Square_(Philadelphia,_PA)|Washington Square]], Philadelphia, 1816. |

| + | |||

| + | Image:1233.jpg|[[Anne-Marguerite-Henriette Rouillé de Marigny Hyde de Neuville]], ''Entrance [[Gate]] to the White House Garden, Washington, DC'', 1818. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:1234.jpg|John Vanderlyn, ''George Washington'', 1834. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0831.jpg|[[Robert Mills]], Sketch for a Monument to President Andrew Jackson, c. 1835–40. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:1226.jpg|[[Robert Mills]], Sketch for a Monument to President Andrew Jackson, c. 1835–40. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:1759.jpg|[[J. C. Loudon]], “Entrance to the [[Flower_garden|Flower-garden]] at Wimbledon House,” in ''The Suburban Gardener'' (1838), p. 641, fig. 267. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:0040.jpg|W. H. Bartlett, “Washington from the President’s House,” in Nathaniel Parker Willis, ''American Scenery'' (1840), vol. 2, pl. 26. Arch is in shadow in center bottom of image. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:1039.jpg|Anonymous, The [[Flower_garden|Flower-Garden]], in Joseph Breck, ''The Flower-Garden: or, Breck’s Book of Flowers'' (1841), frontispiece. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Image:1213.jpg|C. A. Hedin, ''Front Elevation on Live Oak Street'', 1853. | ||

| + | </gallery> | ||

| + | |||

| + | <hr> | ||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

<references></references> | <references></references> | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category: Keywords]] | ||

| + | [[Category: Garden Ornaments/Embellishments]] | ||

Revision as of 11:51, October 15, 2020

See also: Grotto

History

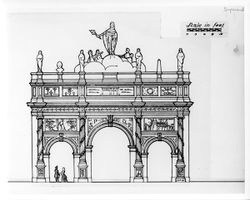

Arch had three distinct, yet interrelated meanings or applications in the context of 18th- and 19th-century American landscape design. The first, which is the most heavily documented, is the use of arches in association with commemorative celebrations, as specified by Ephraim Chambers in 1741 () and reiterated by Noah Webster in 1828 (view text). The antecedents to this practice include the use of ancient Roman arches: large-scale, inverted U-shaped structures, erected to memorialize military victories. In North America, the building of such celebratory arches occurred most frequently in the immediate post-Revolutionary period. For specific festivities, arches were often made of impermanent materials, as in the case of the temporary arch Charles Willson Peale created for Philadelphia to mark the declaration of peace on December 2, 1783. General George Washington’s arrival in cities in the early federalist period was frequently marked by the erection of processional arches, such as the arch of cut laurel and evergreen branches erected at Gray’s Ferry in Philadelphia in 1789 [See Fig. 6]. The arch, with its classical referents, was also the symbol of choice for permanent monuments to President Washington in the early 19th century. The designs of Joseph Jacques Ramée in Baltimore and of George Bridport in Philadelphia [Figs. 1 and 2] not only commemorated Washington’s achievements but also marked the entrance as a space set aside for public use.

These examples point to a second, closely related function of arches as spatial dividers or gates, which also relies upon antique precedents of monumental arches marking entrances to cities or towns. This practice was translated to the American context with shifts in scale and message. Eliza Southgate’s description (1802) of the garden at the Elias Hasket Derby Farm, for example, indicates that arches were used to mark three subdivisions of the landscape and to direct the visitor from the lower to the upper garden (view text).

The third use of the term stemmed from its most basic meaning, summed up by Webster in 1828 as “a segment of part of a circle,” translated in architecture into “a concave or hollow structure of stone or brick”. Peale’s description of the stone arch that he created over the stream in his garden exemplifies this definition of arch (view text). Neither celebratory in nature nor necessarily acting as a spatial divider, the arch created a small cave-like space that Peale tried unsuccessfully to use as a root cellar.

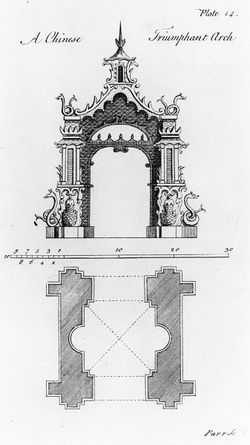

The design or style of the arch varied by context: celebratory arches were typically classical in inspiration, but other styles, such as the Gothic and Chinese, were used for arches erected in gardens. The high, arching spandrels of the Gothic form allowed the erection of covered shelters without walls (with the open arches supporting the weight of the roof), as in Alexander Jackson Davis’s garden arch for Montgomery Place on the Hudson [Fig. 3]. J. C. Loudon illustrated several rustic arches in his publications that were made of rockwork [See Fig. 9] or rough hewn tree trunks [Fig. 4].

—Anne L. Helmreich

Texts

Usage

- Peale, Charles Willson, December 8, 1783, describing his triumphal arch erected in Philadelphia, PA (quoted in Sellers 1969: 196)[1]

- “I am at this time employed in painting a transparent triumphal Arch for the Public rejoicings on the peace, and very much hurried.” [Fig. 5]

- Anonymous, May 1789, “Description of General Washington’s Reception at Gray’s Ferry on the Schuylkill, April 20” (1789: 282)[2]

- “A triumphal arch, 20 feet high, decorated with laurel and other ever-greens, was erected at each end, (a and b) in a style of neat simplicity: under the arch of that at the west end (a) hung a crown of laurel, connected by a line which extended to a pine tree on the high and rocky bank of the river, where the other extremity was held by a handsome boy, beautifully robed in white linen.” [Fig. 6]

- Bentley, William, October 22, 1790, describing the Elias Hasket Derby Farm, Peabody, MA (1962: 1:180)[3]

- “[231] 22. . . . The Principal Garden is in three parts. . . We ascend from the house two steps in each division. The passages have no gates, only a naked arch with a key stone frame, of wood painted white above 10 feet high.”

- Codman, John, 1791, describing the Grange, estate of Dr. John and Sarah Codman, Lincoln, MA (Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, Codman Family Manuscript Collection, box 5, folder 54)

- “1791 Accounts of Sundry Jobs . . . Dr. John Codman Esq. to Thomas Clement. . . April 20 To 40 days work on fences and Espaliers. . . 4/6 . . . 9 . . . 0 . . . 0 . . . to 30 days work on Arches steps and Border Boards 5/ . . . 7 . . . 10 . . . 0.”

- Bentley, William, October 4, 1792, describing the residence of Thomas Brattle, Cambridge, MA (1962: 1:398)[3]

- “[58] 4. . . . I visited Mr Brattle’s Gardens, &c. at Cambridge. We first saw the fountain & canal opposite to his House, & the walk on the side of another canal in the road, flowing under an arch & in the direction of the outer fence.”

- Pintard, John, 1801, describing New Orleans, LA (quoted in Sterling 1951: 230)[4]

- “Over some few [graves], brick arches were turned.”

- Southgate, Eliza, July 6, 1802, describing Elias Hasket Derby Farm, Peabody, MA (quoted in Kimball 1940: 75–76)[5]

- “There are 3 divisions in the gardens, and you pass from the lower one to the upper thro’ several arches rising one above the other. From the lower gate you have a fine perspective view of the whole range, rising gradually until the sight is terminated by a hermitage. The summer house in the center has an arch thro’ it, with 3 doors on each side which open into little apartments and one of them opens to a staircase by which you ascend into a square room, the whole size of the building.” back up to History

- Anonymous, June 25, 1805, describing in the New York Daily Advertiser Vauxhall Garden, New York, NY (quoted in Eberlein and Hubbard 1944: 172)[6]

- “The labour and expence of this establishment has exceeded that of any similar one in the United States. . . [that] he has at a very considerable risk and expence, procured from Europe a choice selection of Statues and Busts, mostly from the first models of Antiquity. . . the walks are ornamented with Pillars, Arches, Pedestals, Figures, &c. the whole of which when illuminated, cannot fail to create pleasure.”

- Latrobe, Benjamin Henry, March 17, 1807, in a letter to Thomas Jefferson, describing the White House, Washington, DC (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation)

- “My idea is to carry the road below the hill under a Wall about 8 feet high opposite to the center of the president’s house. At this point, I should propose, at a future day to throw an Arch, or Arches over the road in order to procure a private communication between the pleasure ground of the president’s house and the park which reaches to the river, and which will probably be also planted, and perhaps be open to the public.” [Fig. 7]

- Forman, Martha Ogle, September 1, 1824, describing the entrance of the Marquis de La Fayette into Newark, NJ (1976: 187)[7]

- “The entrance of La Fayette into Newark was very interesting, he was ushered in by the firing of Cannon and ringing of bells. They had erected on the green a number of arches representing the different states, all wreathed with Laurels and the effect was very beautiful.”

- Peale, Charles Willson, c. 1825, describing Belfield, estate of Charles Willson Peale, Germantown, PA (quoted in Rudnytzky 1986: 24, 41)[8]

- “. . . finding a spring stream in the garden he followed it up the side of the hill, untill it become [sic] of some depth and among large stones—and having at this place made a considerable cavity in the bank, round the source of the Spring, to wall it up this hollow and arch it over, it was thought that it might be an excellent plan to keep cabbage and turnups &c. during the winter season, but on tryal it was found too moist and warm. . . This tryal gave the Idea of building a greenhouse journing to the arched cave—and that Green house keepted all exotice plants perfectly well without the aid of stoves in the severest winters. . .

- “. . . in a part of the Garden where a seat in the shade was often wanted, he built a shed or small room, and to hide that salt like box, and to try his art of Painting, he made the front like a Gate way with a step to form a seat, and above, steps painted as representing a passage through an arch beyond on which was represented a western sky, and to ornament the upper part over the arch, he painted several figures on boards cut the outlines of said figures as representing statues in sculpture.” back up to History

- Peale, Charles Willson, c. 1825, describing Philadelphia, PA (Miller et al., eds., 2000: 5:91)[9]

- “When Peace was concluded between Great Britain & the united States of America, President Dickenson and the Executive Counsil employed Peale to paint a Triumphal Arch in transparent Colours. It consisted of three arches, the Center Arch was 20 feet high, and the side arches each 15 feet high, and the whole length extended nearly to the width of Market street, and it was 46 feet high, independant of the statues of the 4 cardenal Virtues larger than human figures. The architecture was of the Ionic order, ornamented with reaths of Flowers, in festoons and winding round the Columes. It was also ornamented in sundry parts of the building as follows[:]

- “A figure of Peace, represented in a beautiful female figure, and various attendants amidst the Clouds. These were to be lighted by lights placed behind the clouds and out of the sight of the spectators, and doubtless would have had a most pleasing affect in passing down from the Top of the Presidents House to the Triumphal Arch, with a fuse in the hand of Peace, which was to be directed to a fuse which would light 1100 Lamps, & illuminate the whole of the Triumphal Arch in a minute.”

- Loudon, J. C. (John Claudius), 1838, describing the grounds of the Lawrencian Villa, residence of Mrs. Lawrence, Drayton Green, near London, England (1838: 581, 584)[10]

- “The next scene of interest is the Italian walk, arrived at the point 8, in which, and looking back towards the paddock, we have, as a termination to one end of that walk, the rustic arch and vase. . . [Fig. 8]

- “At 26, we have the view of the rustic arch and Cupid. . .” [Fig. 9]

- Knapp, Samuel, 1848, describing the house of Timothy Dexter, Newburyport, MA (1848: 19)[11]

- “Directly in front of the door of the house, on a Roman arch of great beauty and taste, stood general Washington in his military garb.”

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, 1851, describing plans for improving the public grounds in Washington, DC (quoted in Washburn 1967: 54)[12]

- “I propose to take down the present small stone gates to the President’s Grounds, and place at the end of Pennsylvania Avenue a large and handsome Archway of marble, which shall not only form the main entrance from the City to the whole of the proposed new Grounds, but shall also be one of the principal Architectural ornaments of the city; inside of this arch-way is a semicircle with three gates commanding three carriage roads. Two of these lead into the Parade or President’s Park, the third is a private carriage-drive into the President’s grounds; this gate should be protected by a Porter’s lodge, and should only be open on reception days, thus making the President’s grounds on this side of the house quite private at all other times. . .” [Fig. 10]

Citations

- Chambers, Ephraim, 1741, Cyclopaedia (1741: 1:n.p.)[13]

- “ARCH, in architecture, is a concave structure, raised with a mould bent in form of the arch of a curve, and serving as the inward support of any superstructure. . . .

- “Triumphal ARCH, is a gate, or passage into a city, built of stone, or marble, and magnificently adorned with architecture, sculpture, inscriptions, &c. serving not only to adorn a triumph, at the return from a victorious expedition, but also to preserve the memory of the conqueror to posterity. See TRIUMPH.

- “The most celebrated triumphal arches, now remaining of antiquity, are that of Titus, of Septimius Severus, and of Constantine, at Rome, of which we have figures given us by Des Godetz.” back up to History

- Halfpenny, William and John, 1755, Rural Architecture in the Chinese Taste (1775; repr., 1968: 8)[14]

- “PLATE XIV.

- “Shews the Plan and Elevation of a triumphal Arch, to be situated opposite the Front of a Dwelling-house, at the utmost Extent of a large Parterre, through which commences a Long-walk, inclosed by Woods or other rural Plantations. This Arch may be built in a good Manner for about 470 l.” [Fig. 11]

- Repton, Humphry, 1803, Observations on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (1803: 144, 146)[15]

- “If the entrance to a park be made from a town or village, the gate may with great propriety be distinguished by an arch. . .

- “An arched gateway at the entrance of a place is never used with so much apparent propriety as when it forms a part of a town or village. . .

- “The arch should not be a mere aperture in a single wall, but it should have depth in proportion to its breadth.

- “It should have some visible and marked connexion either with a wall, or with the town to which it belongs, and not appear insulated.

- “It should not be placed in so low a situation that we may rather see over it than through it.

- “Its architecture should correspond with that of the house.”

- Webster, Noah, 1828, An American Dictionary of the English Language (1828: 1:n.p.)[16]

- “ARCH, n. [See Arc.] A segment or part of a circle. A concave or hollow structure of stone or brick, supported by its own curve. It may be constructed of wood, and supported by the mechanism of the work. This species of structure is much used in bridges.

- “A vault is properly a broad arch. Encyc.

- “2. The space between two piers of a bridge, when arched; or any place covered with an arch.

- “3. Any curvature, in form of an arch.

- “4. The vault of heaven, or sky. Shak.

- “Triumphal arches are magnificent structures at the entrance of cities, erected to adorn a triumph and perpetuate the memory of the event.” back up to History

- Downing, Andrew Jackson, 1850, The Architecture of Country Houses (1850; repr., 1968: 353, 354)[17]

- “Looking at the exterior of this design, the student of expression will find it marked by dignity, variety, and harmony; . . . harmony in the predominance of the round-arch and other features of the style chosen. . .

- “We see refined culture symbolized in the round-arch, with its continually recurring curves of beauty, in the spacious and elegant arcades, inviting to leisurely conversations, in all those outlines and details, suggestive of restrained and orderly action, as contrasted with the upward, aspiring, imaginative feeling indicated in the pointed or Gothic styles of architecture. . .

- “In calling this villa Romanesque, we only wish to be understood that we have gleaned from that style certain ideas of composition, which, appearing to us well suited for our purpose, we have adopted them in designing a country-house suited to a first class residence here. . .The prevalence of the round-arch, of arcades, of intersecting arches, and of roofs higher than in the Grecian style, but lower than in Gothic styles, characterizes this architecture." [Fig. 12]

Images

Inscribed

William and John Halfpenny, “A Chinese Triumphant Arch,” in Rural Architecture in the Chinese Taste (1755), pl. 14.

Charles Willson Peale, “A View of the Grand Civic Arch,” 1824.

J. C. Loudon, “Seat formed of moss and hazel rods" and "Trellised arches for climbers,” in An Encyclopædia of Gardening (1834), p. 1196, figs. 960–62.

J. C. Loudon, “Rustic arch and vase,” in The Suburban Gardener (1838), p. 581, fig. 231.

J. C. Loudon, “View of the rustic arch,” in The Suburban Gardener (1838), p. 586, fig. 240.

Alexander Jackson Davis, Garden Arch at Montgomery Place, c. 1850.

Associated

Lester Hoadley Seller, A Reconstruction of Peale’s Transparent Triumphal Arch, 1783–84.

James Trenchard after Charles Willson Peale, “An East View of GRAY’S FERRY, near Philadelphia, with the TRIUMPHAL ARCHES, &c. erected for the Reception of General Washington, April 20th. 1789,” in The Columbian Magazine 3, no. 5 (May 1789): pl. opp. p. 282.

Anonymous, “Southern Villa—Romanesque Style,” in A. J. Downing, The Architecture of Country Houses (1850), pl. opp. p. 353, fig. 168.

A. J. Downing, “Presidents Arch at the end of Penna Avenue,” 1851.

Attributed

Robert Mills, Monticello: 2nd version (west elevation), recto, 1803.

Joseph Jacques Ramée, Monument to the memory of general George Washington, to be erected at Baltimore, design for the Washington Monument, 1813.

George Bridport, Alternative designs for Washington Monument, Washington Square, Philadelphia, 1816.

Anne-Marguerite-Henriette Rouillé de Marigny Hyde de Neuville, Entrance Gate to the White House Garden, Washington, DC, 1818.

Robert Mills, Sketch for a Monument to President Andrew Jackson, c. 1835–40.

Robert Mills, Sketch for a Monument to President Andrew Jackson, c. 1835–40.

J. C. Loudon, “Entrance to the Flower-garden at Wimbledon House,” in The Suburban Gardener (1838), p. 641, fig. 267.

Anonymous, The Flower-Garden, in Joseph Breck, The Flower-Garden: or, Breck’s Book of Flowers (1841), frontispiece.

Notes

- ↑ Charles Coleman Sellers, “Charles Willson Peale with Patron and Populace,” Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 59, no. 3 (1969), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Anonymous, “Account of the Preparations at Gray’s Ferry, on the River Schuylkill, and the Reception of General Washington There, April 20, 1789, on His Way to the Seat of the Federal Government, to Take upon High Office of President of the United States,” The Columbian Magazine 3, no. 5 (May 1789): 282–83, view on Zotero.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 William Bentley, The Diary of William Bentley, D.D., Pastor of the East Church, Salem, Massachusetts (Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith, 1962), view on Zotero.

- ↑ David Lee Sterling, ed., “New Orleans, 1801: An Account by John Pintard,” Louisiana Historical Quarterly 34 (1951): 217–33, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Fiske Kimball, Mr. Samuel McIntire, Carver, the Architect of Salem (Portland, ME: Southworth-Anthoensen, 1940), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Harold Donaldson Eberlein and Cortlandt Van Dyke Hubbard, “The American ‘Vauxhall’ of the Federal Era Article Stable,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 68, no. 2 (April 1944): 150–74, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Martha Ogle Forman, Plantation Life at Rose Hill: The Diaries of Martha Ogle Forman, 1814–1845 (Wilmington, DE: Historical Society of Delaware, 1976), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Kateryna A. Rudnytzky, “The Union of Landscape and Art: Peale’s Garden at Belfield” (Honors thesis, LaSalle University, 1986), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Lillian B. Miller et al., eds., The Selected Papers of Charles Willson Peale and His Family, vol. 5, The Autobiography of Charles Willson Peale (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2000), view on Zotero.

- ↑ J. C. (John Claudius) Loudon, The Suburban Gardener, and Villa Companion (London: Longman et al., 1838), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Samuel L. Knapp, Life of Lord Timothy Dexter (Newburyport, MA: John G. Tilton, 1848), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Wilcomb E. Washburn, “Vision of Life for the Mall,” AIA Journal, 47, no.3 (March 1967): 52–59, view on Zotero.

- ↑ Ephraim Chambers, Cyclopaedia, or An Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences. . . , 5th ed., 2 vols. (London: D. Midwinter et al., 1741–43) view on Zotero.

- ↑ William and John Halfpenny, Rural Architecture in the Chinese Taste (1755; repr., Bronx, NY, and London: Benjamin Blom, 1968), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Humphry Repton, Observations on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening (London: Printed by T. Bensley for J. Taylor, 1803), view on Zotero.

- ↑ Noah Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language, 2 vols. (New York: S. Converse, 1828), vol. 1, view on Zotero.

- ↑ A. J. [Andrew Jackson] Downing, The Architecture of Country Houses; Including Designs for Cottages, Farm-Houses, and Villas (New York: D. Appleton, 1850; repr., New York: Da Capo, 1968), view on Zotero.